Discussing Literature Using Seven Levels of Meaning

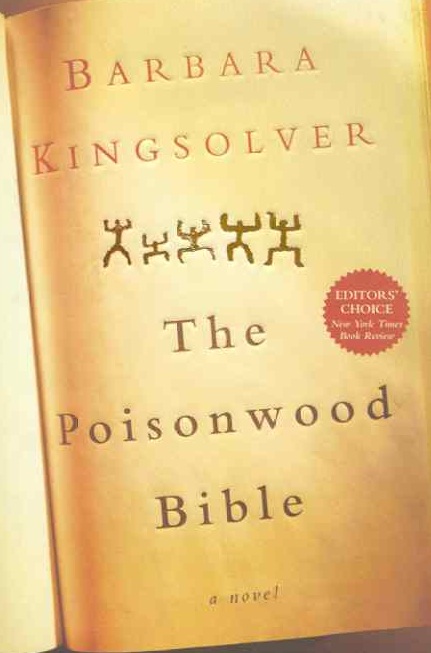

Author Barbara Kingsolver says the question she hates to answer most is “What is your book about?”

I don't like to hear that question too often either, but it seems readers today are mostly interested in plot. "What happens in your book?" Readers want writers to give them the “bullet.” They want to hear “just the facts, ma’am.” And the cover copy publishers provide is usually a snapshot of the plot.

Authors just can't seem to win.

Kingsolver says she would rather have readers ask her about her book’s meaning, which facilitates a longer, deeper, and more enjoyable discussion.

What, then, are some possible levels of meaning in any work of literature?

Seven levels of meaning

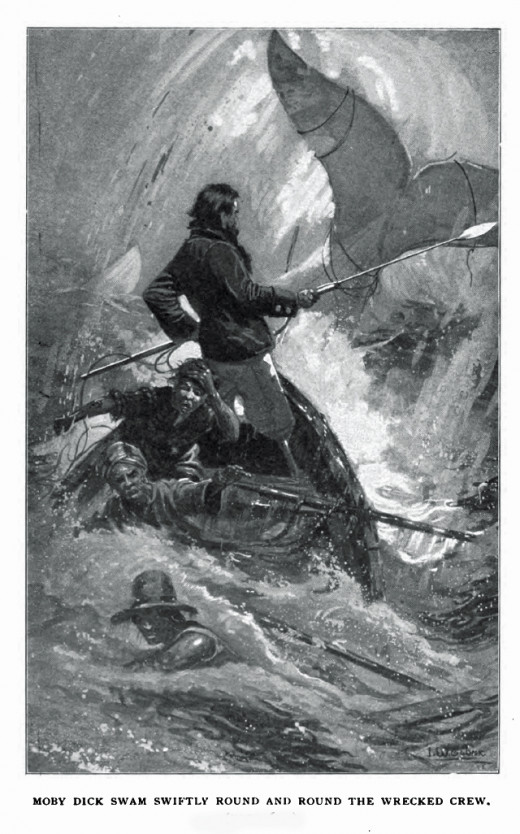

Whenever I discuss literature with my students, I tell them: “We’re going to get deep.” Let’s say we’re discussing Melville’s Moby-Dick. We begin with the surface or literal level of meaning:

“Moby-Dick is about one man’s quest to kill a whale, a quest that ends in disaster.”

This begins our discussion, but it leaves many questions unanswered. Why is Captain Ahab tracking this whale? What kind of man tries to get revenge on an innocent animal? How difficult is this quest? What is the effect of this quest on the crew and the narrator, Ishmael?

Once we have a firm grasp on the plot, we examine the historical level of meaning:

“Whaling ships often spent many dangerous months and even years on the high seas in search of whales to kill for oil, corsets, candles, and toys. The ship’s captain ruled supreme over his crew …”

Once we have a historical context, we investigate the symbolic level of meaning in the work:

“Moby-Dick is symbolic of untamed, untainted nature, while Captain Ahab is symbolic of untamed, tainted human nature.”

We then deepen this discussion by looking at the allegorical level of meaning:

“Captain Ahab is an Everyman in conflict with nature and the unknown, and he reacts to it as most of us would—badly.”

We even dip into the religious or mythological level of meaning:

“Captain Ahab is a modern Jacob wrestling with an angel—or the Devil himself. He is another Sisyphus, punished by the gods to roll a heavy stone up a hill only to have it roll down again. His fruitless, endless search-and-destroy mission will only end in futility, yet he continues to wrestle despite the possible forfeiture of his soul.”

Once I mention the psychological level of meaning, our discussions often take off in exciting new directions:

“Captain Ahab exhibits signs of OCD (Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder) and ODD (Oppositional Defiant Disorder), and he definitely has a Messiah complex.”

We usually finish our discussion with a focus on the sociological level of meaning:

“The class structure on the Pequod favors the ‘aristocratic’ officers at the expense of the ‘plebeian’ crew. Captain Ahab is a tyrant who exploits the crew to further his own dark ends, and he is willing to sacrifice anyone below him—figuratively and literally—to defeat the whale.”

Echoing in our heads

Good literature echoes in our heads. I still have students who remember our discussions of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, Ken Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, and James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

Think of a work of literature that holds the most meaning for you. It may be something you can read more than once, and each time you do you learn something different. As humans, we tend to go deeper into most things in life as we mature, and as readers, we allow some works of literature to become part of us because they echo in our heads long after we’ve read the last word.

I can still hear Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” T. S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men,” and Anne Sexton’s “With Mercy for the Greedy.” I can still see Johnny Gunther getting his diploma in Death be not Proud. I can still feel the emptiness of Gregor Samsa at the end of The Metamorphoses. I still shiver when I think of Dante in the center of hell, I still get goose bumps when I hear Mark Antony’s funeral oration from Julius Caesar, and I still feel the triumph of the human spirit that emanates from Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning.

Now think of a work of literature that meant absolutely nothing to you. I must confess that I fought my way through Fifty Shades of Gray and felt absolutely nothing. What was missing? Meaning was missing. That book meant nothing to me. I believe a work of literature must have meaning to become timeless. The work must resonate with us long after we’ve read it for it to become unforgettable.

Does every work of literature have to have a specific meaning? No! I have been teaching literature for 28 years, and I generally ignore the “accepted” answers in textbooks and allow my students to supply the meanings they see. According to Oscar Wilde, “Diversity of opinion about a work of art shows that the work is new, complex, and vital.” Fifty people could read The Catcher in the Rye and have fifty different opinions, and none of those opinions would be “wrong.”

Does a work of literature have to be complex to be meaningful? No, but complexity helps the work take root in our psyches. Do you always have to “get it” to enjoy or get meaning from a literary work? I don’t “get it” every time, but I love being mystified. Gabriel Garcia Marquez mesmerized me when I was young, and only now do I think I understand him—most of the time. Toni Morrison’s Beloved and Paradise were far too deep for me the first times I read them. Years later, I tackled them again and found myself ruminating over every page, exceptionally glad I had made the effort.

Do works of literature have to be relevant to be meaningful? I believe they do. They seem to mean more to us when they describe us in some way—our way of life, our place in the world, and our hopes, dreams, and fears. When readers tell me they can see themselves in the novels I write, I know I’ve been successful. When readers tell me that they don’t see themselves, I know I haven’t done my job.

Once we begin to peel back the layers and truly immerse ourselves in a work of literature, we’ll often be able to see more than the author originally intended—or maybe what the author intended all along.