Early Modern Japanese Literature

Beginnings of Literature for the Common Classes

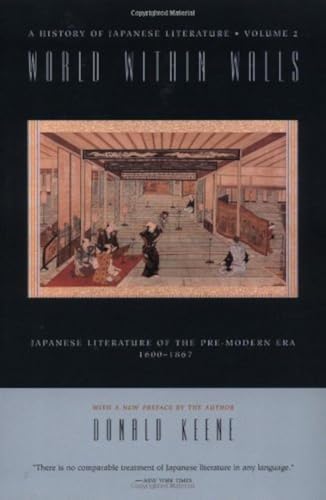

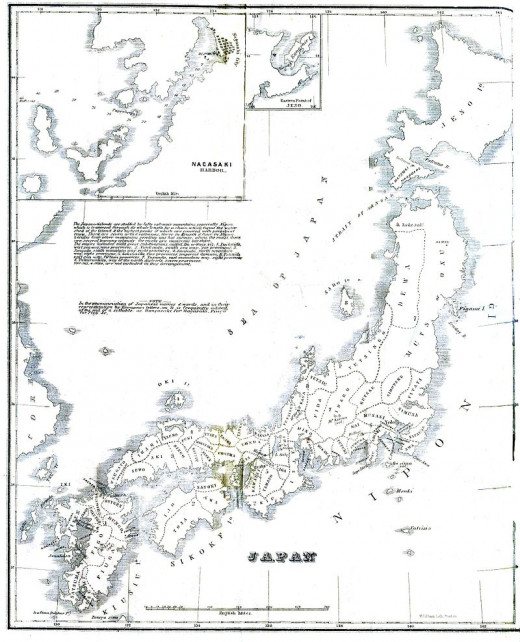

Literature has always been highly prized, regardless of the culture in question; this is well-known. Literacy was typically confined to certain social classes, such as the upper and middle classes including nobility, merchants, and philosophers, and the clergy and monks as well. This has no exception to any pre-modern society, and certainly the early modern period of Japan was not excluded from this unspoken rule. In addition, even when literature came from lower class people, it was not necessarily meant for the low class, as the writing might have been more refined in nature. Donald Keene even points out that although some poetry and prose came from the common people prior to 1600, “the earlier literature was aristocratic in its tone, and both authors and readers for the most part belonged to the nobility.”1 In addition to the relative class restrictions, many cultures have had declines and improvements in literature for various reasons, and just prior to the rise of Tokugawa, this too is no exception: “The sixteenth century, as far as literature was concerned, was a period of beginnings and ends, rather than of fruition. The incessant warfare…had driven the writers of the traditional court literature from the capital to the countryside…Perhaps that is why so many new literary arts germinated in this period…”2 A short survey of some prominent works of the early modern period gives a great insight in how literature was internalized, objectified, and then externalized to the rest of society.

What is interesting to note by this is how literature, and by extension other forms of art which are linked to literature, can be a result of social matters which are present during the time the pieces are written or the style developed. Being such a result, the literature of Tokugawa Japan reflects the happenings of the culture. Tokugawa is often marked with beginning the trend of popular culture, and literature, of course, is no exception that rule. Literacy in the Tokugawa era is at least partially due to direct Tokugawa influence as well as Confucianism and Buddhism, and it began with the Buke shohatto, one of the first sets of laws established by Tokugawa Ieyasu: “The study of literature and of the military arts…must be cultivated diligently.”3 It would seem that literature still took precedence over military arts. Furthermore, it is thanks to many Buddhist temples and schools that literacy reached more people. This foundation of literary growth, then, should be assessed briefly before studying the actual literature of the period.

This priority of literature over military skill is due to the amount of control that Tokugawa wanted to place on the middle classes; while it was expected for samurai and warriors to be able to rise to the defense of Japan when necessary, Tokugawa Ieyasu planned for a long rule of relative stability within the country, without the need for such military prowess, but certainly not wanting to lack it. With the growing stability of the Tokugawa era, the samurai class would naturally begin a relative decline; these warriors often became philosophers, artists, or officials.4 Many of these samurai turned to education and according to Gordon, they, “as well as some priests and farmers…began to offer classes to country people at unofficial schools. These typically met at Buddhist temples…More and more children of farmers learned to read, both boys and girls.”5 In addition, just prior to the Tokugawa era during Japan’s extensive trade with Europe, many technologies came be known, including printing. With the publishing industry booming, literature became more readily available.6 Because of this, too, the Genroku culture literally exploded with novels and writing within the first century of Tokugawa rule. This included hundreds of new titles a year, and the ability to mass produce books allowed each new title to have around three hundred copies.7 The literacy of the era trickled down from the middle classes to the lower classes, something that had not happened prior to 1600, and learning and literature was no longer reliant on social classes. Haruo Shirane writes, “The literature of the early modern period is often thought to be the literature of and by urban commoners.”8

The Emergence of Popular Literature

Early modern writing covers a wide and diverse scale. Three very major, and completely distinct, types of writing and literature came to be prominent in the first few decades of the Tokugawa era, that had not been seen, or at least not in a common sense, before. From the farmer classes, pamphlets and manuals began to be seen, sharing techniques and ideas for more productive cultivation.9 The second was various guides and advice having to do with travel and movement. Third was the literature of the period itself, emerging in a new form of haikai poetry, and kana-zoshi parodies.10 Haikai poetry, specifically comic linked verse, appears to be a blend of the mundane and common way of speaking with a relatively elegant way of writing it.

In short, much of the comic poetry that surfaced in the first few decades of the early modern period has two meanings, some more easily discerned than others, such as a particular renga: “How uncouth it appears,/This autumn evening…Measured by hand/Just six inches big/The moon appears.”11 Renga, or linked verse, often has multiple poets composing verses which answer one another. This particular poem is a short renga, made up of the maeku, and its answer, the tsukeku. Also contrary to this example, some haikaiare less vulgar and more like caricatures of the classic style of poetry, or are simply humorous in effect. A very interesting example of early parodies includes the Inu Makura, or Dog Pillow Book, an obvious caricature of Sei Shonagon’s famous Pillow Book. It may have been written as early as 1607, but was printed between sometime between 1696 and 1715.12 In addition, there were also the “Fake Tales” in the 1640s, parodying the Tales of Ise but also mirroring the society at the time and the suppression of Christianity. One part of it reads, “Don’t burn the fields of Musashi! At Asakusa my spouse has renounced his faith and so have I."13 These kana-zoshi reflect the thoughts and ideals of the common society. Where once the only form of literature that was seen outside of the higher social classes was short poetry, larger pieces of literature were now becoming more common in some of the lower classes. It is this exposure, in a way, which helped to create the Genroku culture, and in turn, the Genroku culture generated parody literature.

Haikai and the Danrin and Teimon Styles

This wave of comical writing reflects the major transition of literacy from the upper to the middle and lower classes of society. It is not implausible to think that the common culture was, essentially, making fun of high class society now that literacy was widely available. The middle classes were imitating the great, isolated literature of the classical periods and placing them in a lower class context, available to the masses. A good example of this form of satire includes the humor of the Danrin school. It definitely was a more free form of poetry, with much fewer rules than the high society haikai. One such poem, composed by the founder of the Danrin style, Nishiyama Soin, reads: “Gazing at/the cherry blossoms/I hurt my neck bone.”14 This is a parody of a poem from 1205 CE written by the famed poet Saigyo.15 Another interesting, from the Danrin style includes:

"White rain

On the eaves of the corner house

Forms into beads.

There is a sound in the wind:

A dog making water."16

One can definitely see how some of the poetry of the Tokugawa Era certainly makes a debut in the more familiar sense, a more ordinary way of thinking and doing. This influence of everyday life, however, must also be taken into account of who was doing the writing. Haikai was not necessarily confined to certain social classes, but it certainly had different roots depending on where it was written. The Danrin style expressed here should be separated from other forms of haikai, in particular the Teimon haikai. As Shirane explains, “Unlike the haikai of the Teimon school, which was based in Kyoto, the center of aristocratic culture, and evoked the classical tradition, Danrin haikai developed in Osaka, the new center of commerce, where a new society of…urban commoners was creating its own culture.”17 Danrin style should not be described specifically as vulgar, but it certainly evokes a feeling of ordinary, everyday, and sometimes rather inelegant matters becoming the center of attention as everyday life.

With the transformation of poetry for and by the aristocracy towards being a more ordinary or widespread commodity will inevitably form the sort of humor that is a caricature of the aristocratic society. Certainly the humor often found in earlier poetry seems to be of a more sophisticated nature, a more witty sort of humor. In contrast, the burlesque style of what would define the Genroku culture between 1688 and 1704,18 was not. One difference that is given between the writers of earlier times, specifically the time of Genji, and the Genroku culture is “Where Murasaki and her circle had made the court their whole world, Saikaku and his friends thought to make the whole world their court.”19 It is important to make another distinction, however, that the Genroku culture was not the period of beginnings for popular culture, but merely the eruption of it.

A few very important writers also came to be known during this period of transition; two in particular rose from the haikai stage and essentially defined the literature of the Genroku era: Matsuo Basho and Ihara Saikaku, two prominent writers with very different backgrounds, and ending with very different styles of writing and influence.

Ihara Saikaku and Matsuo Basho

Ihara Saikaku was born into a respected merchant-class family and at first became a merchant himself.20 Basho was born to a fallen samurai family in a city between the two dominating haikai cities, though located closer to Kyoto than Osaka.21 Despite these two poets living in the same time period (they were born two years apart and died one year apart), their proximity to the two different haikai cultures is obvious in their styles of writing. Both poets began writing in the Teimon style, and for different reasons, both ended up writing in the Danrin style. From there, however, their similarities again split. Ihara, it seems, established his own distinctive style while still associating his work with the Danrin school. He wrote mainly in a prose form, as evidenced by the surviving literature we have that is associated with him. Basho, on the other hand, continued in a different way while still retaining his own ties to haikai poetry. Ihara Saikaku seemed to embrace urban haikai and enjoyed making it his own; Matsuo Basho on the other hand, sought to move away from it once it became so heavily commercialized.

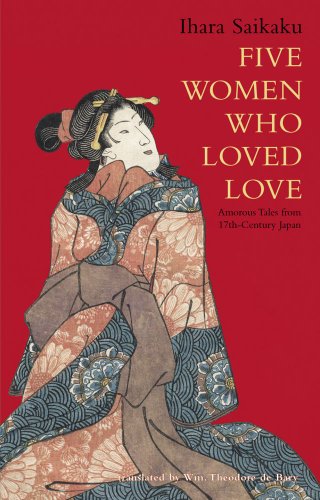

While Ihara continued the style of haikai for which he was famous, such as humor and parody, he moved from writing poetry to writing primarily prose, or at least adopted a poetic prose form. As the author of Search for Authenticity writes, prose fiction had deteriorated "after reaching its pinnacle in Ihara Saikaku's realism."22 Ihara's writings can definitely be considered a type of realism. In the very humor that is present in much of his poetic prose, it duplicates, or possibly represents the authenticity of common life. In most of his literature, there is an obvious play on romantic and lustful relationships, and oftentimes the failures associated with such things, making his writings not exclusive to the happenings in Osaka, but certainly garnering a wider idea of the common people. Saikaku's writing was at once humorous and at times vulgar, but always reflective and moving. Taking an example from one of Saikaku's Five Women, "Gengobei:"

"Gengobei was overcome with the delightfulness of it and wished that Hachijuro remain forever unchanged...Hachijuro smiled weakly. 'There is nothing sure about this Floating World. Who then can tell when life may come to an end?' No sooner had he said this than his pulse failed. The parting he feared had become a reality."23

Reading this small excerpt, one gets a feel for what is said about Saikaku's sincerity for and insightful views on everyday life and love. The story takes place in an area away from "court," placing the context within a common realm. There is no humor in this, only a dramatic irony. However, continuing on with the story, the reader is faced with growing irony, but in a more humorous sense. No sooner has Gengobei pledged his love for Hachijuro and promised to follow him to the grave that he meets another young boy, and he forgets Hachijuro. Again, quite suddenly, Gengobei's lover is gone. In the third part of the story, however, Saikaku's humor truly becomes apparent. He begins with describing the traits of a woman, while similarly describing Gengobei himself. In this part of Gengobei, Ihara describes a young woman who has fallen in love with Gengobei and is bitter at the fact that he is devoted to the way of "manly love." At this point in time, Gengobei has become a monk of sorts, falling into a depression at the loss of his two loves. When she comes to him, Gengobei mistakes her for a boy, and is quick to accept her offer of love: " 'Love is hard to pass up,' he replied coyly, 'even for a priest.' Perhaps Buddha would forgive him. After all, Gengobei did not know his lover was a girl."24 Though Ihara is moving away from a direct parody of classical literature, the reflection of what he sees as "common" society is certainly a parody in and of itself.

The second of the prominent writers of the early modern period, Matsuo Basho, took his style of writing in an opposite direction to that of Ihara’s. Basho continued writing in the renga-style haikai for a while, but the subject matter definitely took a much different tone. Although much of his poetry retained the use of puns, allusions, and a play on words, it was a much more subdued style than the vibrant, obvious innuendo of earlier common haikai. In the Seventy-Six Hokku found in From the Country of Eight Islands, it appears the subjects of his writing here are very interesting, ordinary ideas: “The iris looks exactly like the one in the water.”25 Reading this, the reader might wonder exactly what the meaning might be, or at least the purpose, of such a verse stating something so obvious. It is something to take into consideration when reading poetry during this time. With classical poetry, a deeper meaning might be sought for from the reflection of the iris, a sense of aestheticism perhaps. Or, if there are two irises rather than one, something might be drawn from that. In this poem, however, it is simply stating a fact without searching for some meaning behind the visual.

Another verse, however, is much more suggestive in its context: “At night secretly a worm bores a chestnut under the moon.”26 The relation between Basho’s poetry is oftentimes, not too far off from Ihara Saikaku’s way of writing. Humorous at times, thoughtful at others, but usually with hidden meanings and inventive disguise, Basho was a master of verse. However, some of Basho’s most prominent works are not works of humor or parody. In his Narrow Road of Oku, he writes many poems which are simply reflections of what he sees, and not always in a comical sense. One such poem reads:

"Even a thatched hut

In this changing world may turn

Into a doll's house."27

This poem is a beautiful example of Basho, though not necessarily reflective of the Genroku culture which was spreading far and wide in the first years of Tokugawa. Later in the Narrow Road of Oku, a poem presents itself as a poem that relates well to a more common setting, “Plagued by fleas and lice/I hear the horses staling-/What a place to sleep!”28 Much of what is considered common literature is mixed and influenced by so many different ideas, but the general concept which was used during this time is itself a distinct style.

Genroku Theatre and Chikamatsu Monzaemon

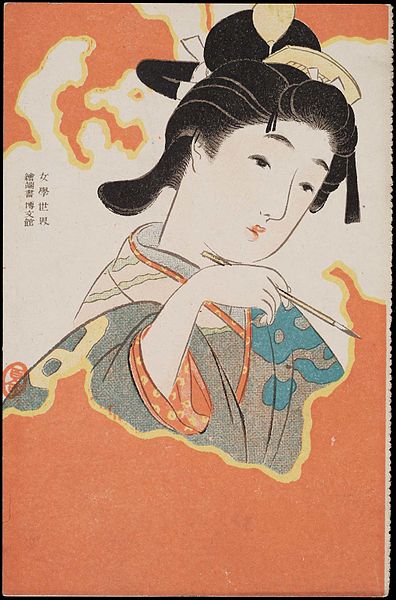

It is also in the Tokugawa era that sees the birth and development of kabuki and joruri for the benefit of the common people, which is in contrast to noh theatre of the upper and middle classes. Like the popular written styles of haikai and kana-zoshi, kabuki often centered around erotic themes, or attempt to evoke that sort of feeling from the plays. As Shirane writes, the people who ventured to see the stages of kabuki “entered an intoxicating, out-of-the-ordinary, festival-like world where the line between reality and dream was blurred,”29 and also states that “The Genroku era was a golden time for kabuki, which played to large and enthusiastic audiences in Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo.”30Kabuki, which is theatre using actors to portray characters, and joruri, or puppet-theatre, were both quite prominent during the early Tokugawa, however kabuki was much more popular with townspeople. Joruri, while considered a popular and common art form, was a theatre that could appeal to all classes of society. Kabuki, much more linked to the culture of the common people, was confined to the pleasure quarters, making it somewhat of an outcaste society: “The contradictory nature of the actor’s position became increasingly apparent, but in the early part of the seventeenth century the spectators attended Kabuki shows for erotic excitement rather than for a display of histrionic ability.”31 In addition, Donald Keene points out that it is possibly thanks to the relative decline of Noh theatre that kabuki saw such a development.32 This could be the same for joruri, though it seemed to have a monopoly over the stage at one point. This is perhaps due to the overbearing restrictions the government eventually placed on the various forms of kabuki and not on joruri.

Kabuki theatre can certainly be considered one of the more interesting aspects of the booming Genroku culture. It survived through numerous Tokugawa repressions, beginning with women-only performers, and when that was banned, young men replaced it.33 In either sense, the purpose was, essentially the same. The first form of kabuki, performed solely by women, was simply a form of prostitution; with the young boys replacing it, the effect was meant to stay the same. Eventually this form was also banned. Kabuki received the harshest treatment of any other form of common culture, and the actors of the Kabuki stage had more restrictions placed upon them than any writer or poet of the Genroku period. According to Gunji’s essay, “the theatrical world…was controlled by a “ghetto” system. All those associated with theatres were officially required to live in the immediate theatre district…whenever they were in public places, for example, they were required to hide their faces with sedge hats;…Officially, the social status of actors was akin to that of the lowliest paupers.”34

From dramatic stages of both kabuki and puppet theatre comes another incredibly important writer of the early modern period, Chikamatsu Monzaemon, who, according to Keene, was “the first dramatist not to have been an actor or manager and to have enjoyed a personal following.”35

Although he was not the first playwright, he was certainly the most popular at the time. Comparable to one of the many trends of Genroku prose, his plays often centered around various scenarios of love and betrayal, and keeping with Chikamatsu’s general theme, are often based on contemporary events, such as the 1707 play The Drum of the Waves of Horikawa.36 In this play, Otane is the wife of the samurai Hikokuro, finds herself faced with longing and lonesomeness in her husband’s absence. True to the over-dramatic irony which is also common for this time, Otane finds herself rejecting the advances of a suitor, who promises to kill them both if she refused him. She responds and asks him if he really loved her, and then she says, “You delight me, why should I treat you unkindly…If you come secretly to my house tomorrow night, I‘ll throw off my reserve.”37 Afraid then that her guest overheard, Otane seduces him to keep him quiet. At the end of the play, Hikokuro has returned, and upon learning of his wife’s adultery, Otane kills herself. “Hikokuro unsheathes his sword and, jerking up Otane’s body, deals her the death blow with a final thrust.”38 The effect of the irony that Otane met with the same death she feared for committing the very act she first refused is not lost on the audience, nor is the overtone within the words and speech used in this sentence.

Dramatic irony, contemporary events, love, betrayal, and all of the comical and laughable ends to such happenings dominate the literature of the early modern period. The effect such words and plays on words is the essence of Genroku literature. Nevertheless, because such writings often mimic society at its worst, the fact that the events of each story can have no alternative ending is what makes this literature so dramatic, and not in a exaggerated sense. Classical literature has elements of aestheticism, elements of honor and nobility. Early modern literature has no such censorship, which is one reason why it is so interesting. It makes the suffering and the irony a human element, something that cannot be avoided because perfection is not reality, nor is a deeper meaning sought for.

The first century after Tokugawa’s stabilization was an explosion of popular culture. Writers who were influenced by a dramatically changing world emerged quickly as the center of a new kind of world. Their influences came from all over and the development of early technologies, as well as the strict system which was placed on the military arts in the first decade of the new era helped to pave the way for the expanding common society. The Genroku culture dominated not just the lower classes but the middle as well, and writers which grew to adulthood within this period continued to influence different schools. Literacy grew, technology allowed it to prosper, and in return, even more literature came into existence from a class which had never before produced their own literature, at least not to the extent allowed before the early modern period. By opening up literacy and by blurring the lines between the classes in this perspective, Japanese culture could only enhance itself and grow, and it certainly prospered.

End Notes

1Donald Keene. World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-modern Era, 1600-1867 (New York, 1976) 1

2Donald Keene. "Joha, a Sixteenth-Century Poet of Linked Verse" in Warlords, Artists, and Commoners: Japan in the Sixteenth Century. Edited by George Elison and Bardwell Smith (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1981) 113

3Ieyasu Tokugawa. "Laws of Military Households" (Buke Shohatto) 1615

4Andrew Gordon. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, 2nd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) 17

5Gordon 2009, 27

6Haruo Shirane. Early Modern Japanese Literature: An anthology 1600-1900 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002) 21-22

7Katsuhisa Moriya. "Urban Networks and Information Networks" in Tokugawa Japan: The Social and Economic Antecedents of Modern Japan. Edited by Chie Nakane and Shinzaburo Oishi. Translated by Conrad Totman (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1990) 116

8Shirane 2002, 5

9Gordon 2009, 27-28

10Shirane 2002, 22

11Renga with anonymous writers in Keene 1976, 18

12Shirane 2002, 23

13"Nise Monogatari" translated by Jamie Newhard in Shirane 2002, 26

14Soin Nishiyama in Shirane 2002, 176

15Shirane 2002, 176

16Takamasa in Keene 1976, 51

17Shirane 2002, 175

18Encyclopedia Britannica Online, "Genroku period" 2012. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/229302/Genroku-period

19Wm. Theodore de Bary. Introduction to Five Women Who Loved Love (Tuttle Publishing, 1956) 25

20Shirane 2002, 43

21Shirane 2002, 178

22Yamanouchi Hisaaki. The search for authenticity in modern Japanese literature (London: Cambridge University Press, 1978) 2

23Ihara Saikaku. "Gengobei, the Mountain of Love" in Five Women Who Loved Love, 198-99

24Ihara, "Gengobei" in Five Women, 218

25Matsuo Basho, in From the Country of Eight Islands: An Anthology of Japanese Poetry, Hiroaki Sato and Burton Watson, ed., (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981) 278

26Matsuo Basho, Country of Eight Islands 278

27Matsuo Basho, in Anthology of Japanese Literature, Donald Keene, ed., (New York: Grove Press, 1955) 363

28Basho,Keene 1955, 370

29Shirane 236

30Shirane 236

31Keene 1976, 233

32Keene in Warlords, Artists, and Commoners, 113

33Gunji Masakatsu, "Kabuki and its Social Background" inTokugawa Japan, 193

34Gunji 194

35Keene 1976, 238

36Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Horikawa Nami n Tsutsumi in Early Modern Japanese Literature, 260

37Chikamatsu in Shirane 2002, 268-69

38Chikmatsu in Shirane 2002, 281