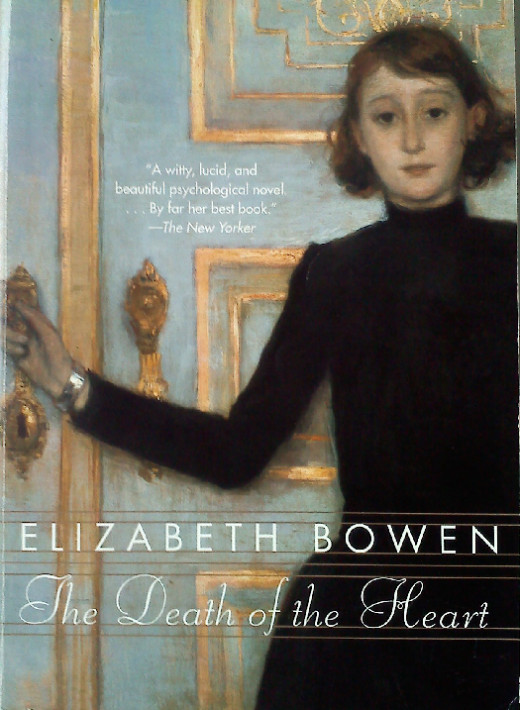

Elizabeth Bowen’s "The Death of the Heart": Anna Quayne's Struggles

In Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart the reader comes to understand that this novel is a search for truth and belonging. Unfortunately, the Quaynes and their unofficial family members are so disillusioned that they pass up the perfect opportunity for a coherent family where everyone’s needs can be met: Thomas needs a more feeling wife, Anna needs a child, Portia needs a mother and father, Matchett needs someone to look over and talk to, and Major Brutt needs stability. As seen in Nostromo, there are two categories of men, those of thought and those of action (Harrod 1). The same division can be applied to the females of The Death of the Heart, especially Portia, Anna, and Matchett.Anna is one of two females who unsuccessfully negotiate their thoughts and actions.

To Help or Not

Anna picks and chooses whom she wishes to help. When Anna does chose to help someone, it is usually a man, for example St. Quentin, Eddie, and Major Brutt. However, Anna does not even give a second thought to helping those that are in a sense her own flesh and blood. Thomas at times reminds Anna how she makes a point of not wanting Portia around (Bowen 42). Anna chooses to be standoffish towards Portia due to Portia’s background. The reader wants to be sympathetic towards Anna who is “highly intelligent and witty and our judgment is complicated by the delight we take […] in the brilliant bravura of her invective” (Corcoran 103). One would think Anna would nurture Portia since they have so much in common, like losing their mothers at a young age (Warren 133). Anna and Portia also share the inability to find their calling in life (Bowen 44). Their sense of loneliness and inability to directly ask for what they want is due to the fact that they are “ignorant of the language which allows people to communicate with each other, convinced that love simply cannot work” (McDowell 14).These commonalities should move Anna to help this manifestation of her younger self. Interestingly enough, Anna cannot extend her ability to help men in need to a female, such as her own sister, in need.

Portia as Reflection of Anna

Anna thinks about how similar her adolescent experiences are to Portia’s, but does nothing to keep Portia from making the same mistakes. The reader is left to believe Portia will end up just like Anna: cold, distant, and disillusioned. Thomas even realizes the potentially damaging effects of Anna’s jealously towards Portia, which is based off of Portia’s youth and ability to have emotions (Corcoran 117; McDowell 13). In the drawing room, Anna remarks how she wishes she could just block out the world and be alone in her own world like Portia seems to be (Bowen 337). St. Quentin is the first to directly state that Anna is jealous of Portia and realize how Anna’s jealousy put everyone in a bad position (404). Anna has one profound instance when she realizes she sets Portia up for failure: “Supposing she were to throw this pack of letters at Portia saying: ‘This is what it all comes to, you little fool!’” (Bowen 323). But Anna never tells Portia of her own failures. Anna even acknowledges how she is often used or misunderstood: “I’m sorry, I was just thinking. I hate my lax character. I hate it when people take advantage of it” (Bowen 31).

What is a Tart?

Tart in this sense is not a dessert or reference to the sense of taste. A tart refers to a young woman who tempts men with her beauty and/or provocative clothing.

Seeking Power

If Anna cannot control her new situation at Windsor Terrace with her half-sister-in-law, she will attempt to have power over the situation by seeking “power over Portia by defining her” (Chessman 78). Anna needs to have control over any situation or else she feels out of place. Eddie confides in Portia that “The thing about Anna is, she loves making a tart of another person. She’d never dare be a proper tart herself” (Bowen 131). Anna has trouble staying out of Portia’s room. Although Anna has no real desire to have Major Brutt around, she takes it upon herself to try to finish the puzzle Brutt sends to Portia (Bowen 150). In talking to Thomas about Eddie, Anna inadvertently confesses her lack of control over any situation: “‘And what do you expect me to say or do? There are limits to what one can say to people and it isn’t really a question of doing anything’” (Bowen 317). And one of these “doing” situations involves writing. Anna has no problem violating Portia private space and reading her diary. This action completely destroys any hope of trust and a relationship between Anna and Portia. Anna can only write letters, something formal and straightforward, whereas Portia is capable of writing a diary, something more personal and active. As St. Quentin believes, “a diary, after all, is written to please oneself” (Bowen 8).

Needs Unmet

Anna’s actions towards Portia prove that she does not understand the needs of others. When Portia first arrives, Anna cannot think of what to do with Portia, so she takes her shopping and immediately sends her off to a private school. Anna is so devoid of feeling and warmth that she cannot “incubate” a child to full term. Ironically, the room given to Portia at Windsor Terrace is what would have been the nursery (Bowen 47). The sign that Portia is meant to be Anna’s “child” is ignored. But Anna becomes aware that she is left childless for a second time as Portia’s running away is like a miscarriage signifying Anna’s lack of emotional success. Portia’s impulsive behavior reminds Anna “what it means to act from the heart” (Warren 143). Anna’s seemingly callous act of laughing at Major Brutt leads Portia to an incorrect conclusion about Anna. Portia’s removal from the adult worlds keeps her from knowing “how valiantly Anna has worked to find a job for the hapless old soldier” (Warren 140). If only Anna took the time to speak to Portia and help her understand her actions, a peaceful coexistence could have been solidified. Ironically, it is St. Quentin that comes to the realization that all Portia wants is to belong (407).

Back to Her Youth

Anna is forced to think like an adolescent in order to figure out what Portia wants the adults to do. However, Anna is at a complete loss considering she is not that far removed from Portia’s position in life. The reason why Anna cannot relate to Portia is because where Anna’s world centers on the aesthetic, Portia’s is centered on “a more realistic […] observation of, and interaction with, the world” (Hopkins 274). This one difference between Anna and Portia is not enough for Anna to be so dumbfounded. Anna holds the key, the last piece, to the puzzle within her because she is so similar to Portia. She, unbeknownst to her, reveals the real issue at hand, “‘How can you know what she’s like when she’s alone?’” (394). All the adults at Windsor Terrace are at a disadvantage because they do not know what Portia is thinking. However, Anna should be able to relate to Portia because nobody really knows what she does in all her time away from home. The fact that Anna is a female, often alone with her thoughts, and isolated from the world in her own way means she does know the right course of action to take to get Portia to come back. Anna refuses to even think about the correct way to handle the situation because she never has cared for Portia much. But it is the fact that Anna, and Anna alone, does not care for Portia’s company that finally makes “Anna clearly [believe] she [is] alone” in her opinion (395). Instead of putting herself in Portia’s place, Anna opts to distance herself from Portia: “‘she and I are hardly the same sex’” (410). Anna’s absolute refusal to be compared, even hypothetically to Portia is insulting.

Works Cited

Bowen, Elizabeth. The Death of the Heart. New York: Anchor Books, 1966. Print.

Chessman, Harriet S. “Women and Language in the Fiction of Elizabeth Bowen.” Twentieth Century Literature 29.1 (Spring 1983): 69-85. Web.

Corcoran, Neil. Elizabeth Bowen: The Enforced Return. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2004. Print.

Harrod, Harvey. Class Notes. Feb. 21, 2007. The College of New Jersey. Print.

Hopkins, Chris. “Elizabeth Bowen: realism, modernism and gendered identity in her novels of the 1930s.” Journal of Gender Studies 4.3 (1995): 271-279. Web

McDowell, Alfred. “The Death of the Heart: and the Human Dilemma.” Modern Language Studies 8.2 (Spring 1978): 5-16. Web.

Warren, Victoria. “Experience Means Nothing Till It Repeats Itself”: Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart and Jane Austen’s Emma.” Modern Language Studies. 29.1: 131-154. Web.

About the Author

Stephanie Bradberry is first and foremost an educator and life-long learner. Her present work is as an herbalist, naturopath, and energy healer. She spent over a decade as a professor of English, Literature, Business and Education and high school English teacher. She is the founder and owner of Naturally Fit & Well, LLC and former owner of Crosby Educational Consulting, LLC. Stephanie loves being a freelance writer and editor on the side.