Expansion Occidentale et Dépendance Mondiale Review

European, and Western, colonialism has been accused of many things, but certainly not of being understudied and un-discussed. There are a huge number of books devoted to the subject, which look at it from a wide variety of different angles. In Expansion Occidentale et Dependence Mondiale, which principally examines the period of the end of the 18th century to 1914 in regards to world expansion, a book examines principally the economic aspects of this change, in a very lengthy, complete, impressive, but also in of itself limited, volume.

Chapters

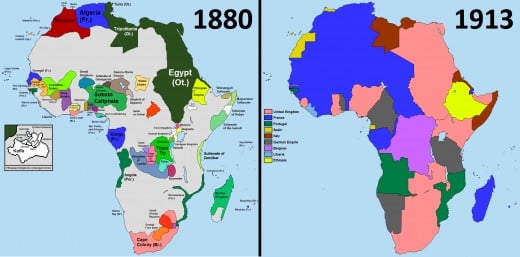

The introduction of the book lays out the times it will study: the three eras of the 18th century to the 1820s, an era of retrenchment in colonialism as the New World broke free, the 1820s to the 1860s as European colonialism began to recover and the industrial revolution took its development in Europe, and then the 1870s to 1914 when a colonial rush broke forth across the world. It also clarifies how certain terms will be used, such as place names and their orthography, national names, and historical terms and their historicity to the time.

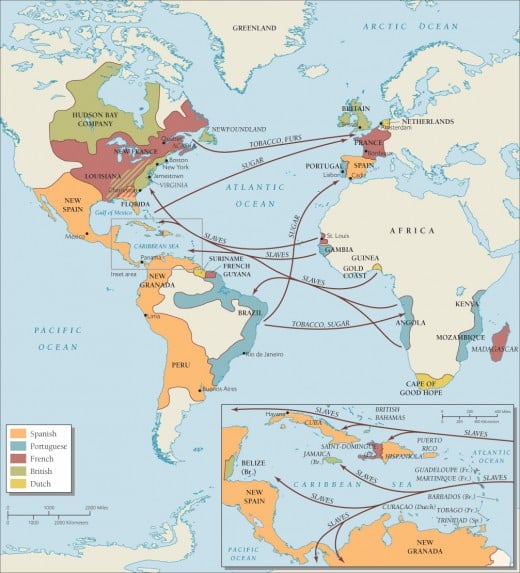

Part 1, De l'économie-monde atlantique aux prémices d'un monde nouveau (fin de XVIIIe siècle - années 1820) ("From the Atlantic world economy to the first signs of a new world (end of the 18th century to the 1820s)), starts with Chapter 1, “Les européens et le monde à la fin du XVIIe siècle) (The Europeans and the World at the End of the 18th century) which conducts an overview of European settlements and colonies around the world in the latter half of the 18th century, including the Americas, North America, Asia, and Oceania, and then of the trade and economic patterns. Chapter 2 “Limites et contestations d’une domination” (Limits and Contestations of Domination) covers the limitations on European colonialism during the period, including resistance, particularly from East Asian nations who refused to engage in European trade, opposition to and shortcomings of European colonial companies and their monopolies, and the wave of anti-colonial rebellions in the British and French Empires which largely destroyed their first iterations. Chapter 3, “Continuités et Mutations. De l’Europe à l’Occident” (Continuities and Transformations: From Europe to the West) explores the ways in which the European world survived and transformed into a Western world, based upon the persistence of the colonial empires, missionaries, the integration of the new United States into the Western order, and the independence, yet paradoxically, the continued dependence, of Latin America.

The second part of the book is “Libre-échange, traités inégaux, et colonisation (années 1820-1860) (Free exchange, unequal treaties, and colonization (1820s-1860s)), covers the rebirth of European colonialism, which added on unequal treaties with other nations as a tool in its arsenal while simultaneously the old chartered monopoly companies disappeared. Chapter 4, “L’Occident, l’industrie, et le monde”(The West, Industry, and the World) explores how European population and industrial expansion drove European relationships with the rest of the world, in a vast expansion of trade and capita happening in a new free trade context. Enthusiastic Europeans wished to build infrastructure abroad, and waves of European missionaries left to the overseas. The abolition of slavery helped to change the image of colonization and ironically to strengthen it in the transformation to new venues. Chapter 5, “Expansion territoriale et coloniale des grandes puissances”, (Territorial and colonial expansion of the Great Powers) covers the expansion of Russia, the United States, the British Empire, and France, and certain elements of their administrative arrangements, followed by a similar treatment of the smaller powers, the Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese. None of the powers expanded greatly in this period, but laid the underpinnings for future expansion such as in the case of France, and focused on better exploiting what they already had. This is explored further in Chapter 6, “Canonnières et traités de commerce” (Gunboats and commercial treaties) which discusses the interactions of European trade, including a massive expansion but not yet colonization in continental Africa, while in Eastern Africa, Zimbabwe was integrated into the world trading system and came under British influence, and European nations competed for Madagascar. Eastern Asia saw European advances but resistance and the Europeans did not gain the commercial advantages they hoped for in opening the country. It was in Latin America that the greatest inroads were made, as many countries were integrated into dependencies of Europe, particularly but not exclusively Britain. Some, such as Paraguay or haltingly Mexico, pursued economic nationalism, but generally with failure. Similarly, European influence grow in the Ottoman Empire, as its attempts at reform only increased its dependency.

The third part of the book, “La domination mondial de l’Occident (années 1870-1914)” (The World Domination of the West (1870-19140)), launches with Chapter 7, “La Belle Epoque de l’Occident” (The Belle Epoque of the West) which principally concerns the economic expansion in the West, which continued to drive increasing patterns of trade with the rest of the world, emigration to the Americas and other new lands of settlement, and the growth of overseas investment of capital. France and Britain, the former economic leaders, were somewhat eclipsed by Germany and the United States, but continued to be important industrial powers in of their own right. Old economic factors, but also social ideas of solving Europe’s problems in colonial expansion, nationalism, and the civilizing mission gave new impetus to colonial expansion. This expansion itself is covered in Chapter 8, “Impérialisme colonial et impérialisme informel” (colonial imperialism and informal imperialism, making clear the complete domination of the world now held by the Westerners, in total colonization of Africa and Oceania, partial colonization of the Middle East, and essentially all other regions brought under indirect control, Latin America in particular continuing to be under extensive European influence but China markedly joining its ranks, with Japanese involvement in its indirect colonization. For non-European states, the problem was that their very attempts to modernize and strengthen themselves increased their dependence on Europe, resulting often in them being turned into colonies, and if not, de-facto colonies. Chapter 9, “Complexités d’une domination. Les autres et l’occident” (The complexities of hegemony: The others and the West) lays out both the complexity of Western control and the resistance it faced. Western control varied in form in a wide range of colonies, and there were debates over relations to native, and countries themselves differed from the “new lands” of the Southern Cone of South America and the British Dominions, to the “third world” countries scattered across the Old World. And although the Western domination of the world as extensive and broad, it was still vulnerable to challenges. Some were ironically its own result, such as the competition of colonial products with European production, or enabling outdated industries to survive through access to the colonial market. European trade with the colonies expanded constantly, at least among the big colonial powers, but whether it was profitable is still a question which is asked. Resistance movements, varying from nationalist revival projects, to popular resistance, to religious uprisings, all desired an end to Western domination of their countries, even if accepting Western influence as a tool against it. Most in the short term failed, except for Japan which succeeded in an impressive modernization of their country.

The conclusion ends in summarizing this colonial development and its results, which had seen the West grow markedly richer than the countries of what would become the “third world”, placed in an inferior position in the international distribution of labor. The empires which had been formed, and the Western domination which stretched across the entire world, escaped only by Japan, would not last. The First World War, more of a European civil war than an imperial conflict, left the empires mostly intact, but the Second began their rapid dissolution, leaving to the world new systems and organizations, even if the world has been permanently marked by the old empires.

Following this are various maps, the general bibliography as opposed to the chapter bibliographies, and the index.

Review

As one starting compliment to the book, there are extremely useful charts which are found throughout. Just to name a few of them, English commerce with India throughout the second half of the 18th century, American trade, emigrants from Europe, capital invested overseas by the British Empire, patterns of French trade. This ties into a theme of the book, in focusing on economic factors, such structural changes which occurred in European influence throughout the world, trading patterns, the position of various regions in the world economy, the profitability of empire, and what drove European expansion. All of this is rather well done, and the book constantly strikes a good balance between generalization and specificity.

This is mirrored in the formation structure that it displays, dividing colonial history into the collapse of the old Atlantic economy and the initial beginnings of a world colonialism, to hesitant imperial expansion, and then the full-fledged Western conquest. While as I express later, the reasoning behind these changes tends to be excessively economic, the stage theory is a reasonable and comprehensible division of colonial history, and helps to marry the detailed complexity of individual events with the development of economic affairs within the West.

Paillard's work is dedicated to the entirety of European colonialism. Thus it naturally focuses on the entirety of the extra-European regions. But if it one has one region which it covers particularly well, it is Latin America, which if not formally colonized during much of the period of the book’s view, was nevertheless in a state of informal colonization. The extent of this informal colonization, where the Latin American countries were turned into dependencies of Europe financially, integrated into the international division of labor, and the extent, nature, and nationalities, of European influence on the continent all receive an excellent degree of attention. It gives both a broad understanding of the region’s development, but also plentiful specific events, such as Paraguay’s special economic development during the first part of the 19th century, Chile and the Second Pacific War, or simply put the independence of the countries. There are occasional primary source excepts which back this up reasonably well, such as the protestations of writers, or an example of one of the colonial concessions in South America (Venezuela) and a description of it.

Such a focus on semi-colonialism and semi-imperialism is also borne out in focus on places such as China, the Ottoman Empire, and Egypt - the last of which, became ultimately a British colony. It shows well how attempts at reform and strengthening often led to a reliance by the non-European nations which ironically left them even more vulnerable and the target of European expansionism.

Social wise it does not have the same degree of attention, such as covering the mechanisms behind colonialism, views on colonialism, the changing intellectual frameworks and European intellectual relationships to the non-Western world, colonial society, and even if it covers resistance to some extent, the ideologies behind it are not except in the broadest sense. Similarly the pressure groups which drove colonialism are not much focused upon, even the economic ones, beyond the most general sense. The book’s focus is overwhelmingly an economic one, with only some small amounts on other affairs towards the final chapter. Furthermore some of its primary sources are dubiously useful: it does not take needing a primary document of the Anglo-Moroccan treaty to understand that British citizens were allowed to purchase property and reside there, or that their ability to impose tariffs was restricted! Furthermore, in placing such intense focus on the economic aspect of these operations, it leaves much less room to important cultural, political, military, etc. reasons for European expansion and colonialism. It mentions the run up for example, to the British annexation of Egypt, but little about the vital importance for the British to protect their trade routes to India and secure the Suez Canal. And while France and Britain receive attention for their expansion, other powers are much less so, although to some extent this is inevitable in the nature of their much smaller empires.

Ultimately, this is a history of colonialism, and while the elements of economic domination were important - for why colonialism developed, for its impacts, for its mechanisms, and for the consequences - even at the time they did not tell the whole picture, balanced as they were by extensive political, and cultural elements behind domination. Even more importantly, as noted above, it paints very little image of the effect upon the populations of colonized societies, and upon the long term impacts of colonialism. Given how complex the subject is, it is inevitable that there has to be a compromise, and for those interested in colonial history, late 18th and early 19th century economic and general history, the history of the industrial revolution, Latin American history which as mentioned it covers in quite some detail concerning informal imperialism and its economic development. and to some extent European political history, outside of Europe, in the same period. Although there generally is little which is truly revolutionary in the book, its well researched material, plentiful information, and thorough work makes it a useful introduction into the subject of colonialism’s economic reasonings, a good reference book, ans as a way to tie the field together for those more intensely involved in it.

© 2018 Ryan Thomas