- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- English Literature

Catherine Isn’t Actually Useless: Realism and education in Northanger Abbey

The Glue Sniffer

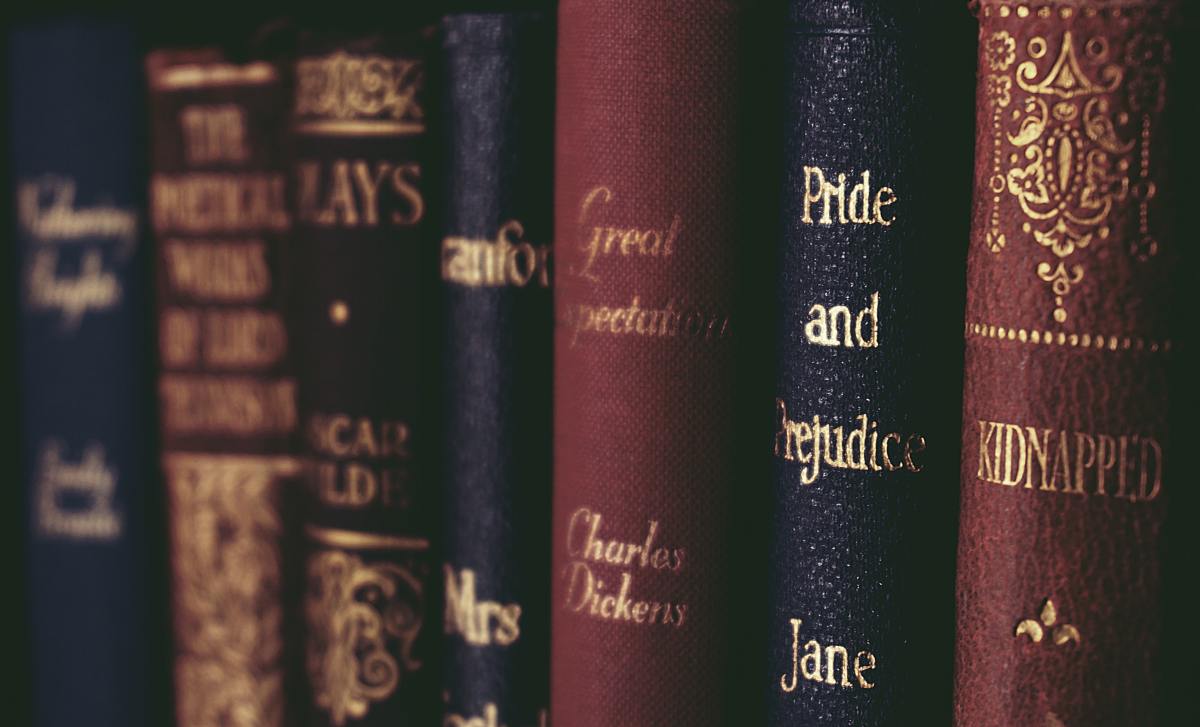

For many Austen fans, Northanger Abbey is a somewhat unpleasant fart in the massive array of constellations sprinkled across the sky of Austen’s prolific literary career. They are less than fond of its heroine, a starry-eyed teenager named Catherine Morland, and they tend to talk about her with a certain degree of embarrassment—like she’s the unplanned kid in the Austen heroine family who sniffs glue and dropped out of school.

Booted aside to make room for literary ladies with more flare and sparkle, she is often sacrificed on the tragic literary altar of critical indifference. She is deemed stupider than Elizabeth, less sympathetic than Anne, and less entertaining than Emma. Furthermore, the cinematic adaptions of the novel that have been sloppily pieced together over the years have not done much to repair her deteriorated image.

Yet Northanger Abbey deserves a place on the bookshelf precisely because it does not take itself too seriously, and in doing so explores profound, underlying warnings of the dangers that can result from romanticism unchecked. Through the humorous depiction of the distorted reality and gradual disillusionment of Catherine, Austen depicts literature and education as being intricately entwined.

Lesson 1: It may shock you, but novels are fictional

Catherine’s gradual acknowledgement of the differences between fiction and real life enables Austen to educate the readers about the value of novel reading, and to additionally explore reality viewed by the readers (the true reality) versus the reality perceived by the characters.

One critic states that “Northanger Abbey opens by posting two kind of readers and two kinds of texts […] the naïve reader of romance who would expect a heroine to be an orphan […] and the more sophisticated reader who rejects romance and who knows a parody when he sees one” (Wallace, “Northanger Abbey and the Limits of Parody,” Studies in the Novel, 20 (3), (1988): 262-273). Austen attempts to create a balance between these two extremes (262), thereby encouraging her readers to grow along with Catherine.

For instance, Austen claims of the supposed heroism of Catherine directly contradict what her “heroine” is actually shown to be like. Thus, the foundation for what will be one of Austen’s fundamental assertions—that reality and novels do not necessarily coincide— is thus initiated within the first pages of the book:

"Her father was a clergyman […] and he was not in the least addicted to locking up his daughters. Her mother was a woman of useful plain sense […] and instead of dying in bringing the latter into the world, as any body might expect, she still lived on […] the Morlands[…] were in general very plain, and Catherine, for many years of her life, as plain as any […] she was often inattentive, and occasionally stupid." (Austen, Northanger Abbey, 13)

The good-naturedness of Catherine’s parents, her own plainness, and her average amount of talent and intelligence all serve as reminders of how the world around her actually exists. When Catherine arranges to go to Bath, she is uprooted from such staunch reminders of reality, and must shape opinions on the new world around her based on the rather ill-informed deductions of her own mind.

Lesson 2: Your friends care about you. Until they don’t.

Catherine is first obliged to interpret (and consequently distort) reality through her early acquaintance with the Thorpe family. Her largest failure is her inability to perceive the true character of Isabella, whose hypocrisy manifests itself in almost every conversation and is easily perceived by Austen’s audience.

Yet Catherine, incapable of separating the world of novels from the world that she lives in, naively compares Isabella’s false sweetness and sentimentality to “all the heroines of her acquaintance” (107). Her inability to perceive her friend’s true nature is not simply due to her natural innocence and naiveté. The reason that readers seem to realize things that she does not is due to Austen’s self-conscious use of dialogue.

For example, Isabella vows to Catherine how she dislikes being stared at by young men, and then proceeds to act contrarily: “ ‘Do you know, there are two odious young men who have been staring at me this half hour. They really put me quite out of countenance’ ” (39). When Isabella later comes upon these “offending young men” (43), Austen ironically states that “ she was so far from seeking to attract their notice, that she looked back at them only three times” (43).

Lesson 3: Men mean what they say. Sort of.

Through Austen’s ongoing ironic commentary, readers are able to step back and observe the story from a more rounded point of view, and are therefore anchored to reality in ways that Catherine is not. Since she is excluded from this reader-author insight, Catherine must gain her true perceptions of reality elsewhere—and this is bestowed upon her by Henry and Eleanor Tilney.

They are Catherine’s substitute for the narrator; by instructing her on how to read, what to read, and how to interpret what one reads, the Tilney’s create for her an appropriate balance between overt sentimentality and realism. Whereas Isabella can only talk frivolously of men and courtship, Henry and Eleanor discuss a wide variety of topics, and their moral and intellectual stability is implied to be largely connected with the books that they read.

While the readers are not often allowed to overhear dialogue that Catherine herself does not hear, they are nevertheless able to combine what is spoken by the characters with what Austen asserts through her self-conscious narration; they are therefore able to form a coherent whole much more quickly than Catherine, who does not, of course, have access to the narrator’s thoughts the way that the audience does.

For example, when we first encounter John Thorpe, he launches into an elaborate and thoroughly uninteresting description of his gig, giving the precise manner in which he paid for it, and coloring his conversation with expletives (43). It only takes about a single page of dialogue for readers to arrive at the conclusion that Thorpe is vulgar and boorish.

Henry Tilney’s conversation is equally revealing. When he teases Catherine about what she shall write of him in her journal, she answers: “ ‘But, perhaps, I keep no journal,’ ”(24) to which Henry replies: “ ‘Perhaps you are not sitting in this room, and I am not sitting by you […] My dear madam…it is this delightful habit of journalizing which largely contributes to form the easy style of writing for which ladies are so generally celebrated’ ” (24-25). His playfulness, as well as his eventual role as Catherine’s literary instructor, is established by the authoritative yet pleasant way in which he speaks to her.

Lessons 4: For God’s sake, read a wide variety of books.

Austen proposes that it is impossible to be an educated reader if one does not incorporate into one’s reading experience the aspects of realism. Furthermore, in order to shape one’s reality realistically, one must realize that discerning good writing from bad linking is irrevocably linked to education. Because the educated reader is able to approach a story with a discerning eye, he can separate the good from the bad and the useful from the frivolous; he is well-equipped, therefore, to gain the moral instruction and intellectual merit that defines a well-composed novel.