Frankenstein’s Creature and the Romantic Period

Frankenstein Themes

From 1785 to 1830 the Romantic Period spawned literature and writers who continue to touch our time. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein illustrates the Romantic age of new beginnings where anything seemed possible, and when traditions were challenged. Her story pulls at many themes including responsible science, feminism, Freudian psychology, and the concept of the sublime.

Concept of the Sublime

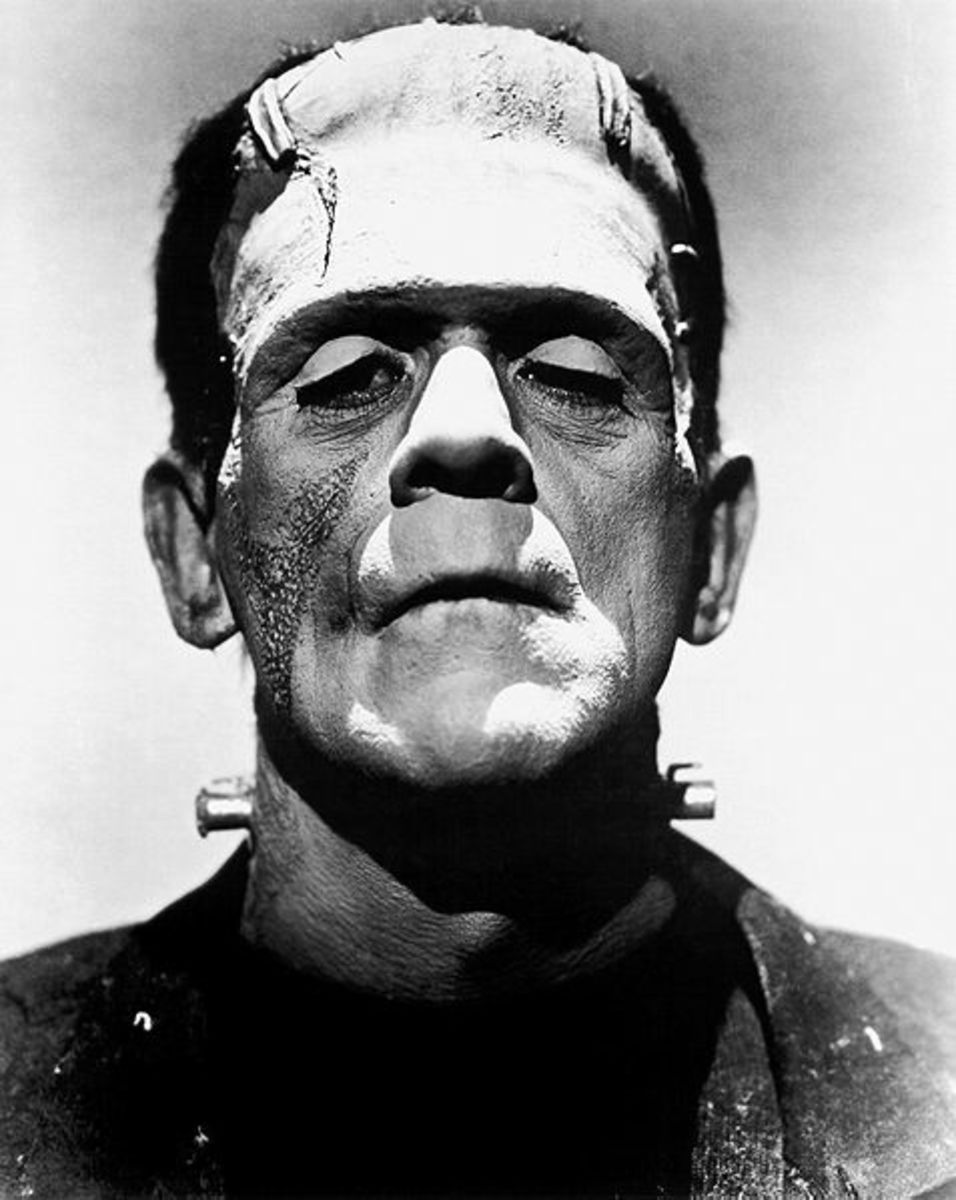

Edmund Burke identifies the sublime as “whatever is in an sort terrible is productive of the strongest emotions which the mind is capable of feeling”. When once the mind has experienced the dread and fear, the fight or flight instinct is to subside, and create a sense of astonishment, which in turn allows one to sense the divine (Mellor 131). Often the sublime is referred to when experiencing the terror that nature has to offer by way of storm or landscape. Mellor attributes the same philosophy to Frankenstein’s creature who not only arouses terror with his appearance, but also with his size and strength. “Above all his origin in the transgression of the boundary between life and death” (Mellor 132), places him in a human context of the sublime. He also lives in and around places of sublime potential, and appears to Dr. Frankenstein during violent storms that are “simultaneous with the revelation of the sublime” (Mellor 131). Eventually the story ends in the vast reaches of the Arctic, yet another “touchstone” of the sublime (Mellor 131-132). Yet one wonders in order to be truly recognised as an entity of the sublime, doesn’t the observer have to reach beyond the absolute terror to an understanding of divine revelation? This does not happen with the monster as his encounters stop far short of the realization of the divine, and remain within the initial contacts of terror.

Responsible Science

A more traditional approach to the divine by way of religion is also present within Shelley’s imagination, if only in her unwillingness to completely abandon Christian values. Where Percy Shelley advocates that “the scientific community [should] … participate in a ‘link’s chain of thought’”, Mary Shelley holds them “answerable to a more familiar code of ethics” (Rauch 14). It wasn’t that Dr. Frankenstein’s mistake came in exploring new methods of science, but “in pursuing knowledge for the sake of no one but himself” (Rauch 14). She believes the scientist must have some kind of connection with “the object of study, … based on respect rather than domination” (Rauch 15). Mellor believes the disrespect, which Dr. Frankenstein displays in treating nature as “the dead mother or as inert matter” leads us as a society to being “capable both of developing and of exploding an atomic bomb” (Mellor 139). Mary K. Patterson Thornburg, in turn, sees the monster as a robot “turning on its creator because of something left out of – or underestimated – in its ‘character’”. The indifferent treatment of nature inevitably leads down a path of destruction where “technology is the doppelganger, reflecting humanity’s scientific achievement, but also its moral inadequacies, and its guilt” (Thornburg 134).

Frankenstein and Freud

Frankenstein is not only a statement on the ethics of science, but “also looks ahead to its century’s end when interest in the human psyche uncovered the unconscious mind” (Griffith). Here we see the monster in terms of “Freud’s splitting of the psyche” (Griffith), where the father of Psychoanalytic Thought believed each of us held the potential of more than one personality. The monster represents Dr. Frankenstein’s doppelganger that rises uncontrollably and performs the secret, unconscious desires of the creator. The dream of Elizabeth’s death shortly after the scientist abandons his creation is interpreted by many as Victor’s hidden belief that she bears responsibility for his mother’s death (Griffith). Even Freud’s Oedipus complex is read into the monster’s actions. The monster’s desire for a mate/companion from his father begs the involvement of incest. Such a companion might be regarded as the creature’s sister, which is also “echoed in Victor’s marriage to Elizabeth” with whom he grew up (Griffith). When “the monster’s threat – ‘I shall be with you on your wedding night’ puts the monster in the nuptial bed” (Griffith), and he later kills his ‘father’, the future ghost of Freud’s Oedipus creeps in to touch the monster with another psychoanalytic theory. While the monster is cursed with many human frailties, he often illustrates the strengths of human character.

The Real Monster

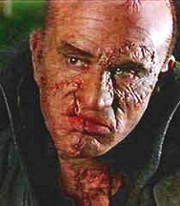

We see within the creature more emotion, intelligence and imagination, than in his creator. Where Victor uses his knowledge to create something for himself; the monster shares his knowledge to the benefit of others. After being rejected by the DeLacy family, the monster employs compassion, and knowledge from Victor’s notes, to save a young girl from drowning (Rauch 8). Yet in contrast, Victor “demonstrates no similar commitment to the application of knowledge in the service of society” (Rauch 8). With Victor’s advanced scientific knowledge and in an age when the experiments of galvanism were showing promise when applied to recently dead asphyxiation victims, the Doctor could have made an effort to revive some of his loved ones. Yet he does not attempt it. Harold Bloom sees the creator as “mind and emotions turned in upon themselves” whereas the creature’s mind and emotions reach beyond and seek “greater humanization through a confrontation of other selves”. Bloom sees the novel as an important piece of literature because it provides a window into the “archetypical world of the Romantics”, where “the profound dejection in … the novel is fundamental to the Romantic mythology of the self” (Bloom). He continues to describe the monster as Shelley’s “finest invention [where the creature’s] narrative forms the highest achievement of the novel…”

Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other, and trample on

me alone, to whom thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection

is most due. Remember that I am thy creature, I ought to be thy

Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel whom thou drivest from joy for

no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably

excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend.

In this, the creature’s self-summation, the reader feels his humanity, and the “creature attains the state of pure spirit … and is racked by a consciousness in which every thought is a fresh disease (Bloom).

Through Frankenstein’s creature we experience the joy of new beginnings, and the pain of rejection. We can see the mistakes almost before they are made, and unlike reality we can also see the solutions. Perhaps in the end, the monster represents ourselves and explains how our less than desirable traits evolve, and in so doing comforts us, and causes us to contemplate and delve into deeper issues. The lack of naming the creature, or of him taking a name for himself, pulls out the truth of human nature. Labels give us the illusion that we know ourselves and others, yet in a life where we are forever growing and changing for better or for worse we can never know for certain what we are.

Works Cited and Consulted

1) Griffith, George V. An Overview of Frankenstein, in Exploring Novels. Gale, Literature resource Centre, 1998.

2) Mellor, Anne K. Mary Shelley: Her Life Her Freedom Her Monsters. New York: Methven Inc. 1988.

3) Millhauser, Milton. The Noble Savage in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in Notes and Queries, Vol. 190, No. 12. Saint Mary’s Website: Literature Resource Centre.

4) Rauch, Alan. The Monstrous Body of Knowledge in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Studies in Romanticism Vol. 34, No. 2, Summer 1995.

5) Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft. Appendix A in Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus; The 1818 Text edited by James Rieger. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 1982.

6) Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft. Frankenstein. New York: dilithium Press, 1988.

7) Shelley, Percy Bysshe. On Frankenstein. The Athenaeum, No. 263. November 10, 1832, p. 730. Reprinted in Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism, Vol. 14.

8) Thornburg, Mary K. Patterson. The Monster in the Mirror (Gender and the Sentimental Gothic Myth in Frankenstein). Ann Arbor Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1987.