Freedom: Not as Free as You Think

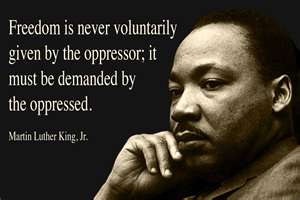

We classify freedom as being able to do what we want, when we want, how we want, with no one else having any say in the matter. However, this is not how the world works. Everyone is answerable to someone, children to parents, workers to employers, citizens to law. Even before birth, our limiting begins. The genetics we inherit, our gender, skin color. Our language is dictated by geography, our culture by our class, our class by our income, our income by our jobs. We quantify ourselves by the labels and boxes that society has created to separate ourselves from each other, and we let it happen.

Benjamin Franklin once said, “Those who desire to give up freedom in order to gain security will not have, nor do they deserve, either one.” We give up certain freedoms to achieve others, and sometimes end up losing on both accounts. Jobs taken for more money might be less stable, and mean more hours working, taking time away from the family that is being supported by the job. We protect ourselves from others by protecting them from us, as well. We avoid acts for fear of retribution and punishment; take part for reward and recognition. We bind ourselves as part and parcel of our existence in society.

There are many facets of imprisonment that are explored between the two texts. Gregor’s experience depicts aspects of physical imprisonment. Gregor’s change imprisons him inside of himself, a human mind within an insect body without the capabilities of communicating his thoughts and feelings with anyone else besides the audience. There is also the fact that he is imprisoned within his room, partly because of a self-imposed exile at his fear and shame over what he has become and his avoidance of his family, and partly because of his family’s growing discontent with his presence. “From this he realized that the sight of was still unbearable for her and would surely remain unbearable for her in the future” (Kafka, 31). Locked within his room, with only his own consciousness for company, there is no discernible escape save death.

There is also the personal imprisonment that Gregor has been enduring prior to his transformation. He is trapped in a job he greatly dislikes in order to help pay off his father’s business debts. Due to his constant traveling and unstable work hours, he is in a solitary confinement of a sort, from his family, and from his friends and peers, as he is left with no time to socialize, make friends, or date. He is incarcerated by the label of his job, relegated to a perceived persona dictated by society as to who and what he is, and how he conducts his business. He is unable to connect with his fellow man due to the revilement of his job, by himself and by the nature of business and society.

Both Clare and Gregor are inmates, in a prison of circumstances, faced with solitude from those that they most wish to connect to, but are unable to. Gregor, due to his inhuman existence, and Clare, due to her superlative need for secrecy as to her true heritage, and the vital necessity of keeping the truth from her husband. Both are faced with the peril of their imprisonment, and fall victim to others’ inability to maintain the status quo, causing their prisons to be destroyed, and them with it.

Clare Kendry’s imprisonment is more imposed be society and its mores at the time. In an effort to extricate herself from a future in the prison of the Colored People label, she crosses into white society, thinking it will grant her more freedoms than she would have had originally, and on the surface, she was right. But when she slotted herself into the persona of being white, she inadvertently caged herself into that world, disallowing her from being able to express aspects of herself, and denying half of her heritage. Her imprisonment is further compounded by her marriage to John Bellew, an unrepentant racist, who has a great probability to do her harm should he ever find out that she is not what she says she is. Pieces of her childhood and adolescence, especially those that have to deal with race, would have to be altered and filtered in the retelling. “I’m simply crazy to go, but I can’t” (Larsen, 16). While initially the denial of part of her heritage had seemed to be in her best interests, she is able to feel parts of herself dying off in the suffocation of self, causing her to initiate actions in which to stave off the stifling nature of her existence. She is spurred into dangerous action in order to restore the essence of who she is.

Clare’s physical imprisonment is her forced confinement to the acceptable areas of white society while her husband is present. For fear of discovery, she only embarks on the journey back to her roots when she deems herself unsupervised. Once she meets up with Irene, there is an escalation of the visitation. This could be a physical manifestation of a hunger that she has carried within, that has been unable to be satiated to her satisfaction, to be present with her own people, a people that she had essentially renounced in order to attain the quality of life that she has always felt that she was entitled to, and would maintain, no matter what the detriment to those around her, or in her way.

Upon meeting up with Irene again, we are presented with the many contrasts between Clare and Irene’s lives. They both face freedom and imprisonment as inverses of each other. Irene is free in her identity by her honesty of what her race is, but blocked by social stigmas against that race. However, Clare, though caged by her Caucasian persona, is allowed more opportunity due to the simple grace of being perceived as being a member of the dominant racial hierarchy. As their interaction continues, Irene is faced with the contraction of her world, due to Clare’s presence, and the need to preserve her secrecy outside those that pose no threat to her. Clare, on the other hand, more than likely felt as though her world was expanding, due to her reconnection to her roots, and the peers that she had once interacted with.

One last aspect of her imprisonment is emotional. Clare is a needful, selfish person, whose personality runs along the lines of that of a spoiled child. “Clare always had a-a-having way with her” (Larsen, 12). There is almost a sociopathic quality in which the way she uses people in order to achieve her ends. While there are brief moments in which she shows a depth of emotion and understanding of her actions, conveying gratitude to Irene for everything that she’s done for Clare, despite her own reservations to the contrary, at heart Clare is determined that by hook or by crook, she will do whatever it takes to get what she wants.

Gloria Anzaldua, as a student of humanity and her own dual heritage, makes us refocus the eye by which we examine the world and these texts. She talks about a limbo state, nepantla, the “in-between state, that uncertain terrain one crosses from one place to another, when changing from one class, race, or gender position to another, when traveling from the present identity into a new identity” (60). This state can be a prison which many of us fall into without notice or escape. It is the transition from one state to another, alterations in identity, and a journey that all of us find ourselves on several times in our time on this plane of existence.

What do we see in this transition, but the distance between extremes? Where we are going, where we’ve been, how we came to be where we are, and where do we go from here? Humanity is such a nebulous state, experience forging each of us equally, but our reaction to the change is what defines. We are the sum of the parts of the whole, as much as we are the individual parts, a duality that many are faced with, but few completely come to terms with. We are faced with identity as a prison, an effort to fit into one box, imprisons us in all boxes, leaving us little room to maneuver and shift and change. We adapt labels to mollify the status quo, striving to find our place among kindred spirits.

So what, at its heart, is freedom? It is being. It is existing, without fear or shame, embracing everything we are, and accepting no limits to what we can do. We are able to don all masks, and be wary of none, no matter where it lies in the shades of gray. Freedom is choosing our own path, and not having it chosen for us. It is being different, and yet the same, as anyone else. It is change, without loss, and gain, without rebuke. It is knowledge and power, and as little struggle as possible to maintain our hold on the two and few worries as to whether or not someone will come along to take it away from us. It is morality, in a just world, with injustice few and far between. It is acceptance of self, and all that it holds, without the difference being assumed to be an abomination or mutation of the human spirit. It is acknowledgement without judgment, and freedom without price. It is free will, freedom to will, and the will to be free.