Get Your Own Big Mac: Tickle's Essay On Greed

Tickling greed

So there’s this lady named Phyllis Tickle (and no, I’m not going to be able to write that last name without giggling). She wrote an essay on greed—uniquely entitled “Greed”— and it is this essay that will serve as the uplifting topic of today’s post. After all, nothing brightens one’s day quite so much as a thorough discussion on what is wrong with you.

Porn, fat men, and big, sexy money

“Greed” was part of a series of lectures on the seven deadly sins sponsored by The New York Public Library and Oxford University Press in 2002-2003. Tickle (*snicker*) admits in the preface that she was rather unwilling to present on this topic because “no one…would have been intrepid enough…to…deliver a public lecture on the subject of greed in the heart of Manhattan,” and that she wished she had been given “a more socially agreeable sin like lust or a more socially acceptable on like plain, old, all-American Gluttony” (Tickle, “Greed,” 17-18).

However, greed she had been given and greed “it was destined to remain” (18).

Make way for the moola

Tickle (I’m an adult, I’m an adult, I’m an adult…) begins by stating that out of all the seven deadly sins, none have garnered so much attention throughout the ages as greed. This is an interesting idea because so many thinkers—including Dante and C.S. Lewis—labeled evil’s wellspring as pride.

Tickle, however, asserts that “whether a religious system conflates or separates vice and sin, the truth remains that every system from Hinduism to Christianity has agreed over the centuries that of our seven demons, greed is the mistress” (12). This puts the traditional Adam and Eve story in an interesting light; one can immediately see the possible connection between their fall and the sin of greed (rather than pride): namely, they desired to be God, coveted God-like nature, if you will, and grasped eagerly at something that wasn’t for the taking.

Clearly, it worked out for them swimmingly.

Additionally, Tickle suggests that discussion and awareness of this deadly sin is not confined merely to theological circles; the fact that this lecture was hosted by universities that are not exclusively “Christian” is but one example, and demonstrates that our occupation with this sin extends well beyond religious systems.

Greed’s costumes

Greed, Tickle goes on to say, is not just man’s greatest virus, but one of his sneakiest. Throughout the centuries, she has presented herself in numerous forms. In our own age, she goes by “laissez faire,” “the social contract,” “free trade,” “the wealth of nations,” etc. (38). She has also employed the tactic of masquerading as a virtue, demonstrated in claims from men like Nietzsche, who state that greed, envy and hatred would become “a potent tool in the perfecting of humanity,” to authors like Ayn Rand, who laud it as a commendable trait worth acquiring (40).

Sharing is for saps

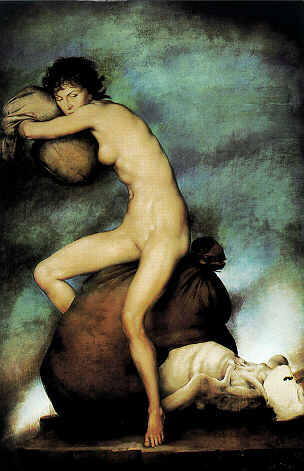

Tickle uses numerous examples of art that has portrayed greed, but to her, Donizetti’s “Avarice” is the most disturbing. A snapshot of this painting was included in the front of the book before I knew what it pertained to (I've included it for you on the right there), and I have to say that I agree with her. It was a chilling thing to look at, and Tickle’s description does a pretty good job of explaining why:

“…her short, curly sensuously tousled hair and her large brown eyes are us…Painted with breasts but without her sex, she sits…astride a lumpy, tight-cinched tow sack and hold another, smaller one up against her sad young face as if to pillow her head there. In her anxiety, she has pulled herself and her sacks off the ground…Behind her, there is not a geographic landscape, but a nonlocative one of the dark, yet luminous colors we recognize immediately as those we inhabit when in prayer or meditation…the stark agony of her existence…stands tragic and eternal…to look is to ache.” (50)

Conclusion: I’m not better than you. I’m just richer

Three points of conclusion here:

First: When I first picked this book up, I was expecting a theological treatise; if that's what you expect as well, put this back on the shelf and go for some C.S. Lewis instead. This essay takes a more historical approach, exploring how greed has been manifested and discussed by mankind throughout the centuries.

However, taking it for what it is, I have to say I’m glad I read it. Tickle is a really good writer. While her voice can be a bit dry and professor-ish at times, she interweaves enough metaphors and descriptions throughout to keep you feeling like you’re actually reading something literary, rather than trudging through a history lesson.

Second: Her claim of greed being the root of all sin is also food for thought. Like most people, I had long inserted pride into this role, but she presents some good arguments for why greed deserves this place instead. It is additionally interesting to discover that out of all the vices, this is the one different religions have repeatedly emphasized as being the worst.

Finally: It's always good to dwell on the reality of the seven deadly sins, especially in this modern age of euphemisms, where we avoid unpleasant realities by masking them in verbal ambiguities. For example, rather than "sin" we say “evolutionary flaw" or “mental illness." Rather than "death" we say "passed away" or "gone on to the big McDonald's in the sky" (don't pretend this isn't what Heaven is). Rather than admitting to a "diet" (admittedly one of the most hideous words in the English language) we say "I'll take the sugar-free syrup" (newsflash: there's no such thing).

In the end, this little treatise strips away our defensive skin and bone to expose the raw, pulsating sore that beats beneath. This is unnerving and uncomfortable, but such clarity brings with it an odd sense of freedom. After all, you can hardly work on fixing something if you don’t know it’s there in the first place.