Housing Benefit Hill: Invasion of the Babysnatchers

She noticed how disturbed some of the other children were, and that there was a certain amount of subdued violence among the staff. She rang the police. This was a mistake...

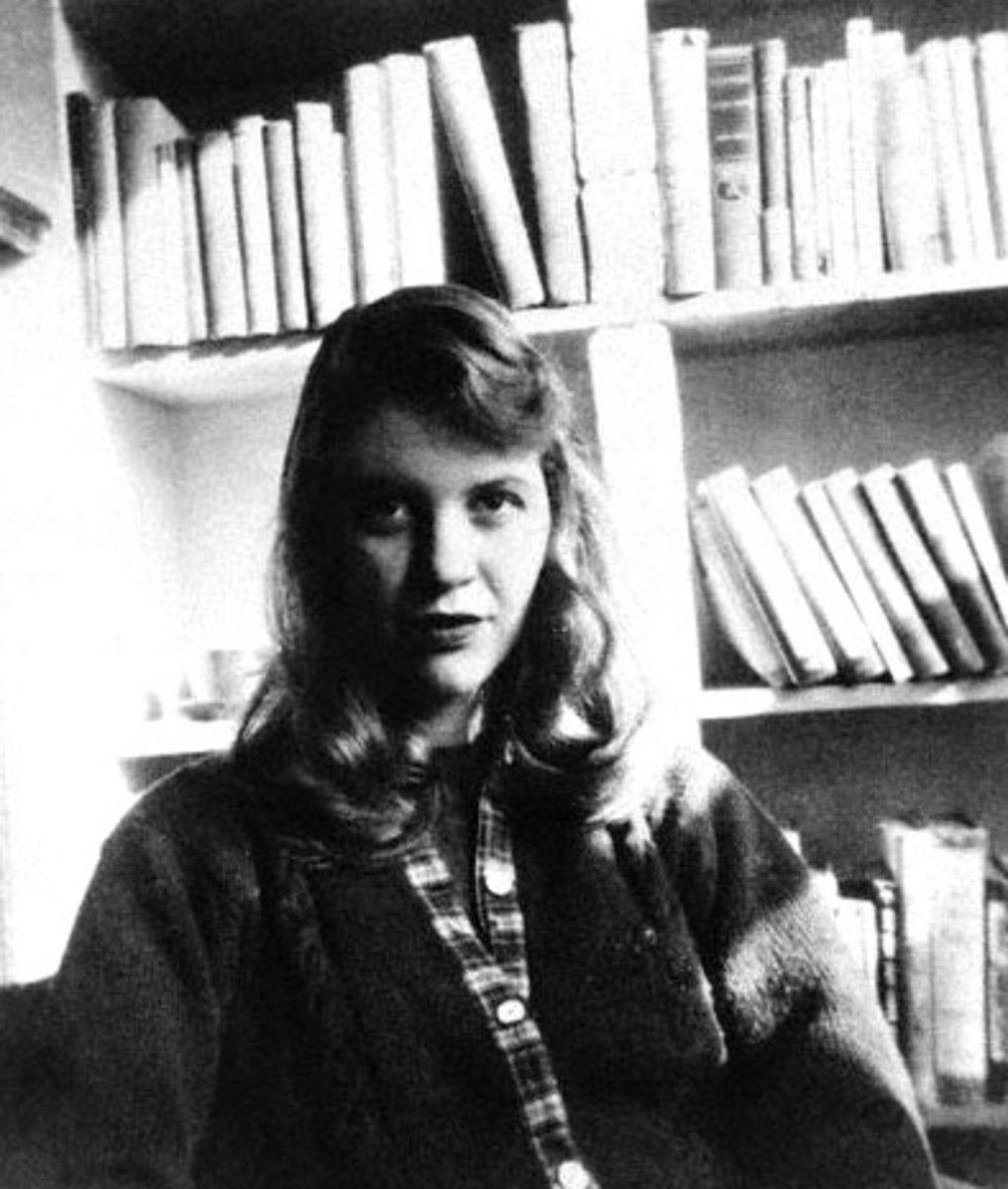

MY NEXT-DOOR neighbour, Sue, was the first person I met when I moved up here. She sent her husband, Martin, around to help with the decorating, and made both of us cups of tea. She's incredibly shy - diffident almost - with a tendency to swallow her words, as if she's no right to say them. It's not that she's inarticulate. She's holding something in.

She's 29 and has given birth to six kids. Only three of them live with her. The first she had when she was 16 (she gave a funny little self-mocking laugh when she told me this). He's since been adopted by her mother. After that she married and had Julie-Anne and then twins, John and Kevin. Kevin died as a baby: cot-death. All of them lived in a B&B. But the husband started drinking. He became violent and had affairs. She walked out on him and moved somewhere else.

Later, she met another man and fell pregnant again. You wonder if she's ever heard of contraception. But I have an odd feeling about her, this mild, simple girl, as if she's always searching for affection, and only finding it this way. And you can imagine: this no-hope family squeezed into dead-end accommodation, dependent on benefits. The social services were alerted, and she was visited regularly.

It was during this time that the dreadful thing happened. She wanted to take the kids swimming, but John was ill so she left him at home with the boyfriend. When she got back John was nowhere to be seen. She asked the boyfriend where he was and he just shrugged and avoided her eyes.

She found him locked in another room, covered in bruises. She rang her social worker, and John was taken to hospital. Later the police came to question the boyfriend and he was escorted away. Later still, police and social workers arrived at her door, and Julie-Anne was taken into care.

Of course children are being taken into care all the time. This is just one more statistic in the terrible catalogue of late-twentieth-century life. And I've no doubt the social workers were acting in the best interests of all concerned. But as I write this, I can't help feeling sick. I can't help picturing her on that day, devastated and alone in her dismal little room, not knowing what was happening, or why.

We all know the feeling when something terrible has happened. It keeps going through your head: if only, if only. If only she'd not gone swimming. If only she hadn't rung the social worker. John's bruises would have cleared up, and no one would have been any the wiser. She could have dumped the boyfriend and kept the kids. If only...

But the kids were fostered out. She went to see them three times a week. And every time there were tears. The kids wanted their mummy back, she wanted them. Floods of tears.

Finally she was allowed to move back in with them, under supervision in a mother-and-baby unit. It turned out to be a home for sexually abused children. Sue was sickened. Her children were not abused.

She was always being watched, had to care for them according to a strict timetable: kids up at such-and-such a time, wash them, breakfast them etc. etc. She hated it. And she began to notice how disturbed some of the other children were, and that there was an element of subdued violence among the staff. She rang the police.

This was a mistake. What she was observing were the day-to-day events of a home for emotionally disturbed children. The staff were merely professionally bored. It was the humiliation of finding herself in this position that had compelled her to act and, of course, there was nothing anyone could do about it. She was branded a trouble-maker and locked in her room; like a schoolgirl. They had a meeting, and it was decided that Sue should leave. She lost the kids once more.

I've said that she was pregnant. After she had the baby, she was told that she would never get Julie-Anne and John back unless she gave this new child up for adoption. They had another meeting. It was felt she wouldn't be able to cope. Meetings, meetings. Sue was bamboozled by the power of their language. She agreed to their demands. The baby was fostered out, and Sue persuaded to visit it. It broke her heart (these are her words) to see it and have to leave it there. She never went again.

It was an uneventful Saturday morning when she told me this story. Julie-Anne and John were watching telly. Her latest off-spring, Anna - a jolly, snotty little creature - was gurgling happily. Martin was pottering about. Sue was sitting hunched up on the settee nursing her mug of tea in both hands. Her eyes were shiny. I noticed a dew-drop forming on the end of her nose before it was quickly sniffed away.

She told me that she'd written the child a letter explaining that it wasn't her fault. She wasn't sure the child would ever be allowed to see it. The ex-boyfriend got 150 hours community service for his part in the "incident", as she insists on calling it, aping the official language that had compelled her to give up a child. It still took two years to get the children back. She was punished for his crime.

SHE'S been up on Housing Benefit Hill for the past four years, trying to make a life for herself. Until last year the children still had care-orders on them, and a social worker would come round and watch her in her home - checking that the kids were clean and well looked after, that she was doing the housework properly - writing it all down on official paper to be discussed at a meeting somewhere. It was horrible, Sue said. She had to swallow her words, curb her anger and humiliation. She couldn't afford to cross them again.

Now we see the origin of that strange diffidence I described earlier. When she met Martin they ran a police-check on him to see that he was all right. And when she was pregnant with Anna she refrained from telling them about it for a while. They told her off for that: "Thought we were going to be honest with each other, you know, and all that crap." Nothing in her life belonged to her, not even her own body.

What makes me angry is that anyone who sees her with the kids (and it doesn't take some deep study to see this, no social reports, no psychological theory) can tell immediately that she would never harm them: not in a million years. And it's obvious, too, how much they love and care for her. John, particularly, is immensely protective of her. He looks out on the world with such weary old eyes, as if he's seen all the hurt there is to see.

© 2009 Christopher James Stone