- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Books & Novels»

- Nonfiction

Identity Issues in Roberta Sykes' 'Snake Cradle'

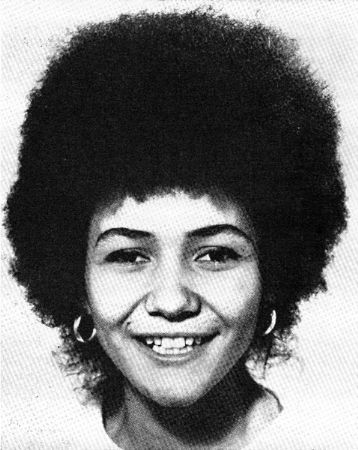

Roberta Sykes is widely criticized by the Australian Aboriginal community for her autobiography Snake Cradle, in which Sykes is accused by some as intentionally misrepresenting herself as Aboriginal. Despite Sykes never actually claiming she is Aboriginal in the text, members of the Aboriginal community interpret the inferences of Aboriginal identity in the book as being a claim of Aboriginality Cregan, 2001:172). This critique of Roberta Sykes’ autobiography Snake Cradle analyses the development of her self-identity as a result of her experiences, and of institutional discourses in Queensland during her childhood. Additionally, it deconstructs why the Aboriginal community regard her self-identity (ambiguously portrayed in the book), as being unauthentic. Before exploring the aspects of Sykes’ childhood that lead to her controversial adoption of Aboriginal identity, issues in defining identity are explored.

The autobiography Snake Cradle and the contention it raises among the Aboriginal community regarding what constitutes Aboriginal identity, demonstrates the difficulty involved in defining identity (Herrero, 2005:76). Foucault (as cited in Danaher Schirato and Webb) believes “discourses shape our understanding of ourselves” and that our “thoughts and actions are influenced, regulated and to some extent by these different discourses” (2000:31). Foucault’s belief corresponds with the constructivist perspective of identity. As quoted by Kurtzer (2002)

Constructivist understandings view identity as being constructed through discursivepractices and are concerned with systems of representation, social and materialpractices, laws of discourses and ideological effects. (103)

In respect to Sykes’ childhood this constructivist view may support her right to claim an Aboriginal identity, considering the similar experiences of racial discrimination she shares with Aboriginal people. Alternatively, Kurtzer (2001:103) also discusses the essentialist understanding of identity, explaining this concept as being based on the invariable or fixed properties that define a given entity. Those who believe Aboriginal identity is derived from genetic inheritance support this essentialist concept. Considering the uncertainty around Sykes’ parentage, applying the essentialist view is debatable. For example, Sykes’ mother who is arguably presented as a fair skinned Aboriginal woman passing as white, adamantly denies being connected genetically to Aboriginal people throughout the autobiography. The possibility of Sykes inheriting indigenous heritage from her father remains evident within the text. However, there is a strong emphasis on the belief that he was in fact an African-American soldier. Debate over whether a person is entitled to claim an Aboriginal identity on the basis of their genetic inheritance, or on their involvement within Aboriginal society, indicates there is no general agreement in the Aboriginal community as to what determines Aboriginality (Kurtzer, 2001:105). As there is no way to prove Sykes’ genealogical heritage, the construction of her self-identity by the influences of institutional discourses requires further analysis to understand how her identification with Aboriginality developed.

Experiences of discourses and relationships within public institutions such as schools and state bureaucracies plays a significant role in the construction of Sykes’ self-identity. Most notably, the experiences of racial discrimination she encounters from within the framework of the education system. Furthermore, her numerous, almost identical confrontations with the Queensland Police are evidence of an embedded racial discourse between police and Aboriginal people in the 1950’s. Sykes’ first significant realisation that people are perceived differently according to their appearance occurs when she is six years old. Her mother becomes ill, and Sykes and her sister Dellie are left in the care of an orphanage in Rockhampton. The girls are perceived as Torres Strait Islanders by the nuns, and are subsequently placed in the Islanders dorm. Segregation of races within the orphanage reveals to Sykes her difference from the white children, and her similarity to the coloured children. Further strengthening her newly discovered black identity, Sykes is subjected to racial remarks from the other children. Separation from families, and placement in institutions is a common experience for Aboriginal children in Queensland at this time. Kurtzer (2003:52) argues that this episode develops a sense of connection for Sykes to the Aboriginal experience, though her time in the orphanage is brief, and does not necessarily reflect the experiences of most Aboriginal children, who often were not reunited with their families.

After returning to her family and school in Townsville, Sykes’ awareness of her difference to the other students is emphasised when a visitor refers to her as the “coloured girl: (Sykes, 2005:51). Throughout her childhood, and particularly within the education system, Sykes suffers various instances of racial discrimination. At the age of fourteen she is expelled from school, despite being apparently bright, well behaved and having a strong desire to continue her education. The text indicates that her expulsion at the age of fourteen is the normal process for coloured children at the time. She is also then refused entry to a state school on an apparently insubstantial pretext. Once again the author infers her exclusion is directly attributed to racial discrimination from the institution. Experiences of prejudice and discrimination continue to shape Sykes’ self-identity as she progresses through varying stages of her young life. Additional factors in Sykes’ construction of Aboriginal identity are her encounters with the Queensland police.

Danaher, Schirato and Webb (200:37) state that public institutions “draw their authority from their capacity to speak the truth about some situation”. Sykes’ frequent encounters with the police (Sykes 2005:192, 204, 218), and their recurring perception of her as being an Aborigine ‘off the reserve’, and under the Aborigine Protection Act, would serve to reaffirm the young Sykes’ identity as Aboriginal, through the institutions position of power, authority, and its “capacity to speak the truth” (Danaher, Schirato & Webb, 2000:37). Furthermore, this prejudice from the police is another experience Sykes shares with Aboriginal people further strengthening her empathy and attachment to Aboriginal Society. Despite Sykes sharing relatively similar experiences with Aboriginal people, many argue that she did not have an authentic Aboriginal experience, and as such, that she has no right to infer she is Aboriginal in her autobiography. One of the main issues of contention surrounding Sykes is her adoption of the snake as her totem.

Perhaps the most significant reason for Sykes identifying with Aboriginal culture—and subsequently the most significant criticism of her—is her adoption of the snake as her totem. Sykes describes in her autobiography her relationship with an elderly Aboriginal man who begins teaching her to recognize attributes in people that are also adopted by animals. During one of their conservations, Sykes, who is depicted in the book as being stubbornly inquisitive about her identity, asks the man “Who am I?” His reply is “You fella’ snake” (Sykes, 2005:110). Sykes’ identification with the snake by a relatively unknown Aboriginal person is repeated during a family trip to Ingham. Sykes once again befriends an elderly aboriginal man, who identifies Sykes as being of the “snake people from North” and like the previous man, refers to her as “you fella snake” (Sykes, 2005:170). These snake identity encounters have an obvious impact on Sykes’ concept of self-identity and lead to much contestation over what Aboriginal identity entails.

The notion of Aboriginal identity expressed in Sykes’ text has generated considerable debate and anger among the Aboriginal community (Kurtzer, 2001:104). Some believe she has no right to claim an Aboriginal identity based on her life experiences and ambiguous genealogical heritage. Although Sykes never actually claims an Aboriginal identity, Kurtzer (2001:105) believes Sykes’s autobiography encourages readers to perceive her as Aboriginal. Kurtzer (2003: 171) quotes Aboriginal academic Professor Gracelyn Smallwood as proposing Sykes is “incorrectly portrayed in media” as Aboriginal. Supporting the comments of Professor Smallwood, Pat O’Shane (Cited by Kurtzer, 2001:104) argues that Sykes experiences do not entitle her to claim an Aboriginal identity, as they are fundamentally different to those of “every other Aboriginal kid in Queensland”. O’Shane is likely referring to contrasting elements in Sykes' life such as being a coloured girl attending a predominantly white catholic school, and her freedom from the Aborigine Protection Act, that significantly restricted the lives of most Aboriginal people in Queensland during Sykes’ childhood. Moreover, O’Shane observes Sykes’s success as a writer, as being directly attributed to the conveyance of Aboriginal identity within the autobiography. Sykes’ response to such accusations is to argue she never directly claims Aboriginal identity (Cregan, 2001:186). However, the adoption of the snake as her totem is interpreted by many in the Aboriginal community as a direct claim of Aboriginality. Sykes was in particularly opposed by the Birrigubba Juru Bindal clan, of whom the snake totem belongs.

Sykes’ narrative relates experiences of racial discrimination similar to those experienced by Aboriginal people in Queensland in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Accordingly, many have misconstrued Sykes as being a part of the Aboriginal community. Media portrayal of her as Aboriginal contributes to this misrepresentation. However, the concept of Aboriginal identity is not agreed upon; consequently, the issue has become progressively contentious. Further debate on what constitutes Aboriginal identity is necessary to define the concept and avoid future misrepresentation.

References

Cregan, K. (2001). Aboriginal Identity, art and culture. The Years Work in Cultural Theory. 8(1), 172-226.

Danaher, G., Schirato, T., & Webb, J. (2000). Understanding Foucault. NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Herrero, M., D. (2005) Snake Dreaming: The life-giving and life-taking of the snake. Australian Literary Studies, 22(1), 73-89.

Kurtzer, S. (2001). Identity dilemmas in Roberta Sykes' autobiographical narratives, Snake Cradle and Snake Dancing. Australian Feminist Studies, 16(34), 101-111.

Kurtzer, S. (2003). Is she or isn't she? Roberta Sykes and authentic Aboriginality. Overland, 171, 50-56.

Sykes, R. (2005). Snake Cradle: Autobiography of a black woman. NSW, Allen & Unwin.