Ils Ont Fait la Paix: A Distinctly Average Versailles History

One of the most important things with any history book is to figure out the audience and what it is hoping to achieve. There are serious differences between books which are written for popularization of a subject, and books written as a serious foray into a topic. Ils Ont Fait la Paix is intended as a general history of the Versailles Treaty (and other post-WW1 peace treaties) for popular consumption. I haven't, admittedly, read many books of this level on the subject - most of my reading comes from articles or tangentially through more advanced works - but the result does not appear particularly impressive. Ils Ont Fait la Paix provides something of a decent overview, but without very much vigor and with important omissions. Except as a basic introduction, it is mostly to be avoided.

The introduction to the book lays out the scene of 1919 with the collapse of the Central Powers and the armistice, and the difficult task awaiting the peace makers, with a heavy emphasis placed on the American president Wilson.

Following this, the first chapter concerns the aims of the involved great powers, France, Britain, the United States, Italy, Germany - and the revolutionary turmoil in Germany - and Japan.

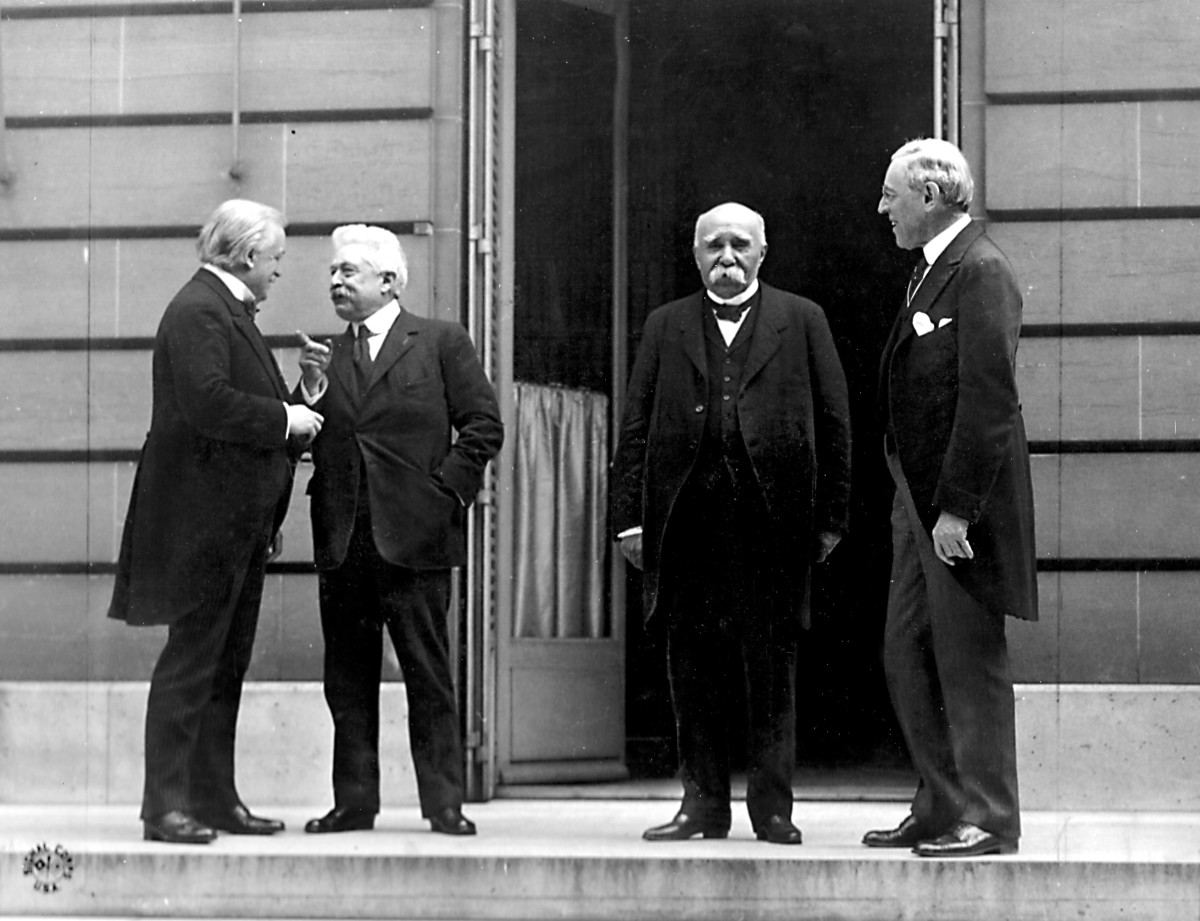

The second chapter concerns the decision makers, ultimately a small group of individuals representing three nations - France, Britain, and the United States, with Georges Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Woodrow Wilson, with Italy being snubbed politically and the Japanese only being interested in special matters. Much of the chapter is a character portrait of the representatives of the five great powers.

Chapter three is about the League of Nations, with Wilson's ideal of it, the reaction of the various powers, particularly the Anglo-Saxon nations, but also the French who entertained doubts about its ability to actually protect their security. It also discusses the Japanese interest in a racial equality clause and their own divided reactions to the idea of the League of Nations. Continuing on with the structure of the LoN, and its relevant articles in the Treaty of Versailles, it notes the actions of the LoN and its failures, as well as its legacy for the future where it served as a predecessor for the United Nations.

An equally spiny issue was reparations to repair the vast damages Germany had inflicted on the French and Belgians, as well as for the Allied powers as a whole to attempt to repay their war costs through money from Germany. Here, it paints a picture of an intransigent France and grasping UK, with relative American moderation, notes the problems of coming up with a precise figure, and relays the long term problems with making Germany pay.

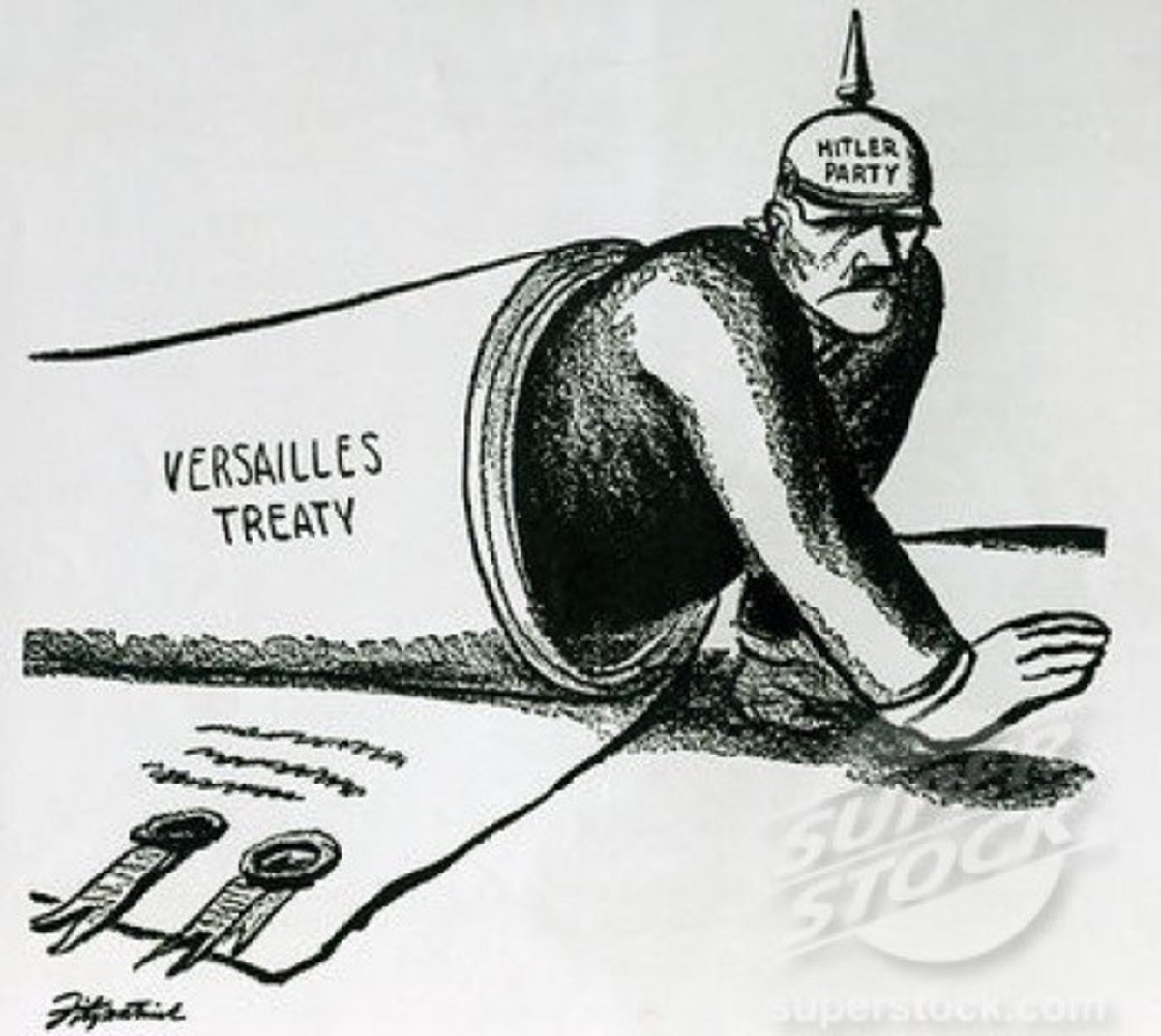

Another crucial part of the treaty was to constrain Germany, done through military disarmament - which once more paints a picture of a rather benevolent Anglo-Saxon perspective for German land forces, and a strict French view. After this comes the territorial adjustments for Germany, focusing principally on the Polish border, the Rhineland, and Alsace-Moselle. Economic reparations were also important for controlling German strength, with both resources demanded from Germany and also internationalization of key aspects of its economy. Finally it notes the intense German hostility to the treaty, particularly fired by Article 231 which declared the Germans responsible for the war. This would be a lodestone around the neck of the new German state, dramatically harming its long term legitimacy.

Moving on from Germany, chapter 6 looks at the division of Austria-Hungary, following the fortunes of each of the successor states with Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Poland - although not noting anything about Romania...

The former Ottoman Empire receives its attention with the internal chaos and independence movements in the former Ottoman Empire, and the Franco-British rivalry over the spoils of war. Its disemberment gave impetus to Arab nationalism and Zionism, as well as a Turkish revival which would put an end to the Treaty of Sèvres which sought to impose foreign control over much of Turkey.

Colonial territories is the focus of chapter 8, with the colonial ambitions of the victorious nations, the new mandates system which was created to fulfill Woodrow Wilson's declaration of a fair colonial treatment - partially just a colonial annexation, partially a genuinely new structure in international law. Of course, this had some motivation by racism, discussed concerning Woodrow Wilson and European leaders.

Chapter 9 is about Italy, with the Italian rivalry with Yugoslavia over Adriatic coastal territories, and in particular their goal of obtaining Fiume - ethnically Italian, but surrounded by Croatians and vital to the new Yugoslavia's economic integrity. This resulted in an affair of Italian paramilitary units being allowed to occupy the city, the Italian representatives at the Versailles conference quitting Paris to try to pressure the other Allies: although these failed Italy was ultimately able to secure a reasonably positive and advantageous peace treaty, despite claims of a "mutilated victory".

Japan's fate was similar as expressed in chapter 10, as it lacked weight and interest on most questions other than Asia at the peace conference. It managed to gain Shangdon against the Chinese and many German Pacific colonies, but failed to impose its racial equality treaty.

Comically the United States ultimately rejected the treaty it had played such an important role in crafting, with Wilson failing to convince the necessary majority of Americans concerning the League of Nations and compromising American sovereignty by involvement in it. The "isolationism" adopted by the United States afterward still however, involved significant US international cooperation and ultimately the US would play a decisive role in the creation of the UN during and after WW2

Chapter 12 examines the rise of fascism in Italy, Germany, and Japan, fired by real or imaginary offences, and their policies. In Italy, Mussolini - although he would be relatively moderate for the first decade of his leadership - in Germany the increasing polarization and problems of Weimar even if the mid 1920s provided a temporary stabilization. the rise of Hitler, and Japanese radical nationalism.

The final substantive chapter concerns appeasement to Germany, French and British foreign policy in the 1930s and 1930s including the French attempt at Franco-German rapprochement, and the lead-up to WW2.

The conclusion draws the normal verdict about Versailles in academic circles: that it was a valiant effort but undermined by the retreat of the Anglo-Americans from European affairs, differing national priorities and intractable differences, and the weakness of the UN, and that it was the effects of the Great Depression that put paid to the Versailles system, rather than it being in of itself worthless. Despite its problems, the Treaty of Versailles would leave important legacies to history about self-determination, a determination to end war forever, and law and justice as the order of international affairs.

The Treaty of Versailles is one of those historical events which continues to generate controversy even until today. In popular opinion tends to be reviled as an incredibly foolish peace treaty which led to German hostility and anger and then to the Second World War - but there is also a reasonably broadly-based academic view which stresses the treaty as being a response to difficult circumstances and which did its best to attempt to respond to a diverse range of priorities. Ils ont Fait la Paix: Le traité de Versailles vu de France et d'ailleurs broadly is positioned in this stance, in what might be viewed as mildly revisionist, standing against the orthodox view present for decades proclaiming the Treaty as an inherently catastrophic and unjust disaster, itself at its origin a revisionist stance on the Treaty.

Key to this understanding, is the word " cautious". The great central theme of this book is its caution. It is moderate in its claims, and doesn't aim to make any great and sweeping revisionist claims, or significant claims in general beyond this exceedingly unambitious stance - that the Treaty of Versailles was an attempt to provide a treaty for a difficult position and which was let down in large part by the events of the following decades.

There are crucial elements of information missing. For example, in the beginning of the book it mentions the various objectives of the great power nations involved in the Versailles Peace Conference - the British, Germans, French, Americans, Japanese, Italians, etc. But the amount of detail here is extremely lacking - Germany for example, includes next to nothing about their actual aims, besides them hoping for a lenient peace. Other books do provide this. To quote Germany Tried Democracy; A Political History of the Reich from 1918 to 1933, pages 137-138:

"In April, 1919, the German government laid down a number of instructions to be used by its representatives at the Paris peace conference. It stressed the point that Wilson's program, which it regarded as binding on both sides, would have to be made the basis of the peace. It demanded a free plebiscite in Alsace-Lorraine. It rejected the separation of the Saar and the left bank of the Rhine from the Reich. It likewise insisted on keeping the great coal mines of the Saar under German control. As regards the frontier with Poland, the Scheidemannn government felt that a plebiscite was indicated in one area only, Posen. Here alone, it held, was the population indisputably Polish. West Prussia could not be ceded because that would mean the severance of East Prussia from the Reich. The cession of Upper Silesia was also inadmissible because the large amount of coal produced there was vital to Germany's existence and because the people of the region would be adversely affected by union with Poland. The latter would receive privileges from the German government which would take care of her need for free access to the sea. A Polish corridor to Danzig was out of the question. Northern Schleswig's right to self-determination by means of a plebiscite was conceded. German territories now occupied by Allied troops would have to be evacuated when peace was concluded. The American note of November 5, 1918, was to he the basis for any settlement of the reparation question. This meant payment only for damage to civilians and their property. The blockade, which was still in effect except for carefully stipulated food supplies, would have to be lifted promptly. Germany would have to regain control of her merchant fleet. In her economic relations with other countries, she would not allow herself to be fettered or handicapped. Her colonies, which had been overrun by Allied armies, would have to he returned to her. She asked only that the principle of equality be adhered to in this matter. She was prepared to serve as a mandatory under international supervision if the other colonial powers consented to do likewise. Unilateral disarmament of the Reich was rejected. Disarmament would have to be carried out on an international scale and in accordance with the principle of reciprocity. Germany definitely favored the formation of a League of Nations; she was sympathetic to the idea of settling international disputes by means of arbitration. She wished immediate admission to the League on the basis of equality with other countries. As for the Allied charge that Germany alone was responsible for the outbreak of the war, it would have to be denied forcefully and unequivocally.

This is an excellent and clear laying out of exactly what the Germans proposed as their own peace settlement: there is no equivalent to this in Ils Ont Fait la Paix. In general for most powers the amount of detail and specifics is quite lacking concerning their peace treaty policies, only their general philosophies and ideals. Sometimes this can be misrepresented as well - for example, Foch's proposal for Germany's army was 200,000 short term conscripts, which was actually larger than the Anglo-Saxon proposal for 100,000 long-term service soldiers, which is not mentioned in the book and which constantly attempts to portray the Anglo-Saxons as more lenient concerning German army size.

The same can be said about the French negotiation position. The book is very quick to define the French as intransigent towards Germany and a partisan of a harsh line to limit German power. While this is broadly speaking perhaps correct, especially in the public sphere, historians such as Mark Trachtenberg have shown that the French had alternate peace proposals, including overtures to the Germans that sought a degree of rapprochement, such as different reparation schedules - indeed, the book settles too firmly on the side of harsh French reparations, without focusing on the French attempt for inter-allied economic cooperation to resolve the problems of European economic reconstruction.

Some chapters do seem better. The section on Italy is well done, showing the internal Italian political response to the question of Fiume, both afterwards, but less often talked about, during the crisis, with the occupation of Fiume by the Italian nationalist D'Annunzio, showing the rather strange and heady mixture of policies and rhetoric adopted by D'Annunzio during his time occupying the city, and also how it was interpreted abroad.

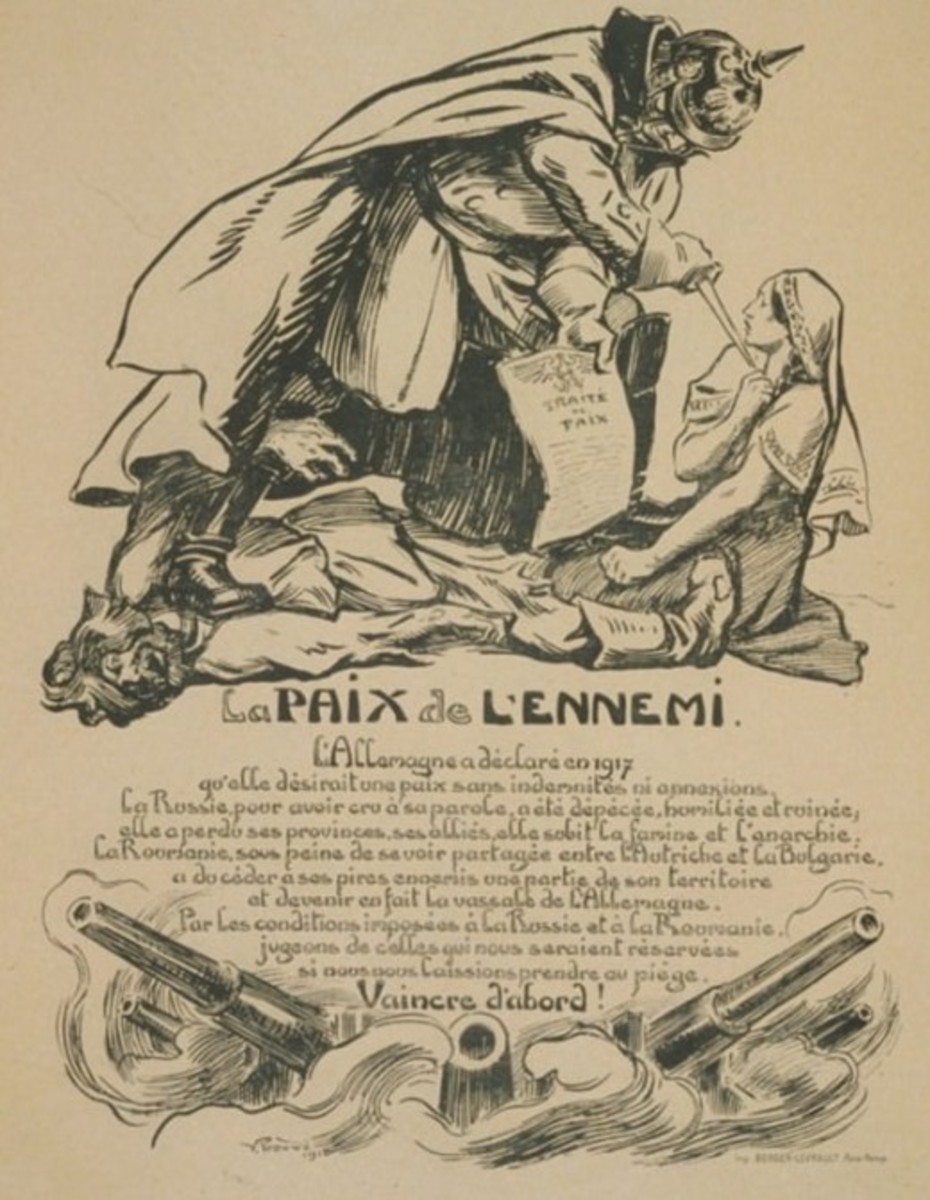

There are also decent maps and images to support the book, with each of the treaties including reasonably good maps to cover them, as well as various pictures of events happening during the period, such as the meeting in the Hall of Mirrors, celebrations at the Armistice, refugees, etc. While none are particularly striking, they are workable and complement the book well.

For an introduction into the post-WW1 peace treaties, Ils Ont Fait la Paix is a decent book, but generally dry, uninspiring, a perfect example of a committee project which has arrived at producing a consensus without much spark or elan left. For those seriously interested in the subject, there are no footnotes to look at claims, only the bibliography at the end, and the book lacks key areas of information as mentioned above. If it had confined itself merely to the Treaty of Versailles as it proclaims to do in the title, there might have been the space to enable it to set up a sufficiently detailed and exhaustive history of the German peace treaty: the dilution of its strength by simultaneously covering the Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian, and Turkish peace treaties definitively amputates its central theme. For anybody with more than a passing knowledge of the the post-WW1 peace treaties, Ils Ont Fait la Paix is an unnecessary book. If any book can have almost everything within it learned on Wikipedia, then its role is a doubtful one in the current age.

© 2020 Ryan C Thomas