Indians, Puritans and Feminists

"Hobomok" & "The Wept of Wish-Ton-Wish"

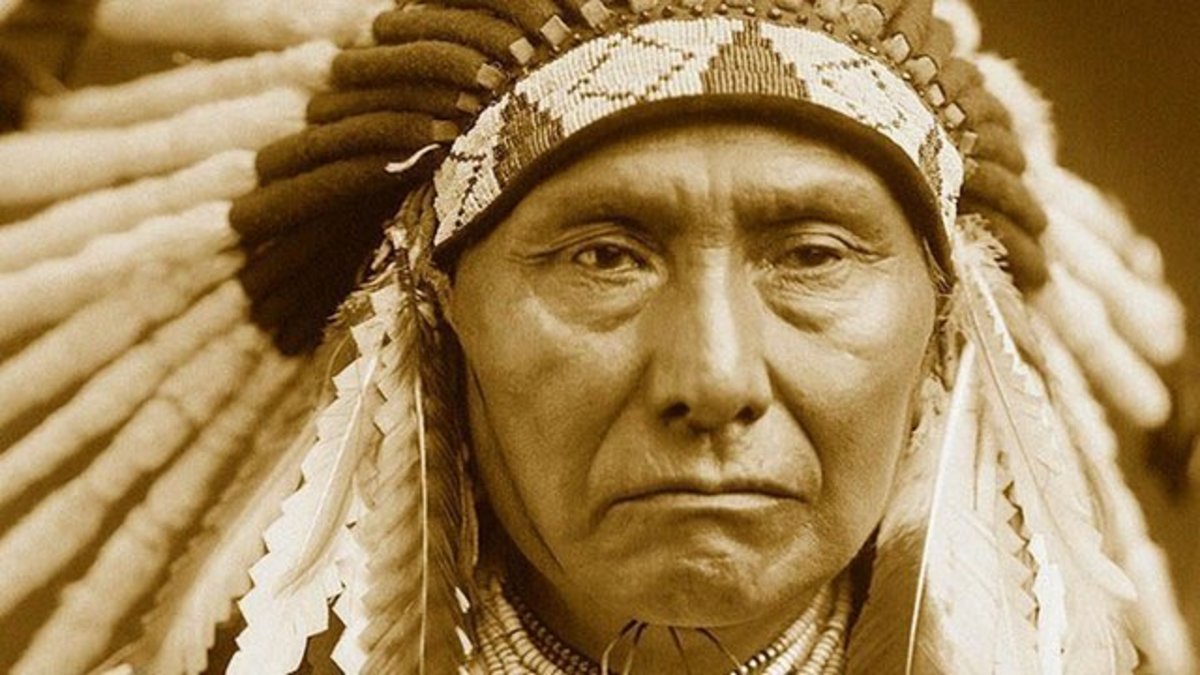

In this essay, I will take a closer look at the two novels "Hobomok" by Lydia Child and "The Wept of Wish-ton-Wish" by James Fenimore Cooper. These novels are both related to early American settlement and the Puritans that lived there, living both in harmony with and in quarrel with the natives. However, it is also necessary to consider the contemporary time they were written in; the 19th century. The authors also have different genders, which with the political agenda would provide them with different starting points and political views. The introductory part of the essay will present the authors, as their political views and social backgrounds are important to discuss their intentions upon writing these works and discover how the social reforms of their time has affected their novels.

Why would these 19th century authors return to the topic of Puritan religion, upon encountering the social Antebellum period's battle for female rights?

About the authors

Lydia Maria Child (1802-1888) was born into a family of abolitionists which influenced her education heavily. In the 1820s she kept busy as a literary figure, writing historical novels, teaching and publishing a children's periodical called "Juvenile Miscellany". She married the editor David L. Child in 1828 and this, combined with her encounter with William Loyd Garrison was the most important factors which led to her dedication to abolitionism. (EB writers, 1998)

Child was politically active through this cause and published a lot of different kinds of literature to further their cause. Her best-known work is An Appeal in Favor of That Class Americans Called Africans (1833) which made her socially shunned and resulted in her periodical being cancelled. Her book was a success despite of this and for two years she also edited the National Anti-Slavery Standard. (EB writers, 1998)

Lydia Maria Child was a force to be reckoned with throughout her life, serving as her country's "conscience" (SNL, Johannesen, 2009) She was a spokeswoman for the rights of black people and women, and human rights in general up to her death in 1888.

James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) grew up in Massachusetts, in Cooperstown, which was founded by his father William. He studied briefly at Yale University, but was expelled and enlisted in the navy from 1808-1811. The year he left the Navy was consequently the year he also got married to the woman that would kick-start his career as a writer. SNL (Store Norske Leksikon) writes that his wife made him live up to his word upon having criticised a reading of a novel by claiming that even he could have done better. His "Indian-books" are well known, and through his career as an author he is one of the writers that have most influenced the way Americans view their country through his historical accuracy and portrayal of different ages of the American history. It is natural to consider him for a position as one of "America's literary pioneers" (SNL, 2009)

Cooper also founded "the Bread and Cheese Club" where American authors, editors and artists would meet at Washington Hall to share a meal and discuss their dabbling with the arts. Other members were scholars, politicians and other high-status characters with an interest in the arts. Cooper was a liberalist and moved to Europe to have his four daughters educated, a luxury he would not find in 19th century America. (Dekker, 1998) Although he wanted his daughters to be formally educated, Cooper was a man who believed in previously defined gender roles. His interest in politics were presenting him with social changes he was living through, and several of his novels he tries to incorporate these changes while still holding own to his own values. (Zeitvogel, 2004)

Cooper and Child are both considered a part of the Knickerbocker School, which was a 19th century regional group who "sought to promote a genuinely American national culture and establish New York as its literary centre". (EB writers, 1998) Encyclopaedia Britannica (EB) defines both Cooper and Child among the most important members.

The political agenda

The antebellum period and its many reformers created the first feminist movement in the United States. The roots of this nineteenth century movement can be found in the inequalities between the sexes at the time, but also in "material and cultural changes affecting the way women saw themselves (Walters. 102)." With economic developments came great change, and the fact was that the best new opportunities were reserved for men. Femininity was tied to the home, childbearing and thereby separated from political life and from career-opportunities. Because of the new technology, a woman's home life became easier and the lowered birth-rate made sure their duties were increased. Still, the men were the ones who worked and controlled the financials of the household and provided the money needed to raise children. The impression was that men were" naturally strong in body and mind, aggressive, and sexual. Women were innately weak, passive, emotional, religious and chaste (Walters. 102-103)." Today, these explanations show signs of beliefs that women are inferior, but the nineteenth century women saw some of these traits as something to cherish. Intuition and emotion were traits that made them different from men, but in a good way. "Some writers went so far as to suggest that feminine traits were morally superior to masculine ones […] (Walters. 103)." Some women stated that the differences between men and women allow them (in a justified way) to divulge in activities outside the home, and amongst these was the notion of "reform".

Although the earliest part of the reform made no real impact, this would soon change. This change came when the reform met another social struggle; Antislavery, or abolition. The most accepted theory as to why women's rights reformers turned their heads towards antislavery was that the struggles of the black man and the woman were similar. When women fought for the betterment of the black people's situation, they became even more aware of their own identity within the society. ""The comparison between women and the coloured race is striking," declared Lydia Maria Child […]. Both are characterized by affection more than intellect; both have a strong development of the religious sentiment; both are excessively adhesive in their attachments; both… have a tendency to submission; and hence, both have been kept in subjection by physical force, and considered rather in the light of property than as individuals (Walters. 105)." This statement is filled with stereotypes for the radical purpose of stating that both women and coloured people are "morally sensitive (Walters. 106)." This term opens for the view of these two social groups as people who are good, but who have been oppressed by the white males of society.

Lydia Child's "Hobomok"

In her novel, "Hobomok", Child takes us back to the 17th century and the Puritans of Salem in its beginnings as a settlement. She introduces the plot of the novel as something taken out of a manuscript written by a male ancestor of hers, which she has taken the liberty of making into a story worth telling in a novel. When considering the contemporary social debate of feminism, however, a probable idea is that she uses this male ancestor as a tool in order to make her own thoughts and opinions more relevant and attractive to those who were opposed females' right to write and support their own thoughts. The general belief that women are too ruled by emotion to compose their thoughts into something of value, seemed to be a factor even in the 19th century, thus the need for Child to promote her novel in this way.

Upon reading about the Naumkeak (Salem) settlement we meet several characters and families, the main character being Mary Conant. Her mother is sick, her two brothers have died, and her father is a Puritan of heart and soul. In addition to this, she fancies a man, Mr. Charles Brown, who belongs to the Episcopal Church, a form of Christianity her father disapproves of, claiming it is lazy and wrong towards Jesus. In the first chapter of the novel, Child, disguised by the notion of a male ancestor, depicts Mary in the forest, performing a Native American ritual. The ritual has her draw up a circle, and is supposed to summon her future husband to come and join her in it. The Native American Hobomok appears and joins her, but she is afraid of him. Shortly after Mr. Brown appears, having been awoken by a dream that she was in danger and thus coming to make sure she was all right. He doesn’t take the ritual seriously, and claims that even if it would work, Hobomok's appearance wouldn’t affect her future. Hobomok questions why he can't have love for a white woman.

Another character who is central to the plot is Mary friend Sally Oldham, whose father is an associate of Mr. Conant. Sally is being doted by another member of the Puritan church, Mr. Graves who, on the beach upon Child's ancestor's return from England with his young bride, tries to kiss Sally against her will. She strikes him in the face, prompting a conversation between herself and Mary later, which reveals the characters of their fathers. Mary confesses that she is glad it was Sally's father that witnessed her strike Mr. Graves, instead of her own. Sally agrees and notes; " Though he is your father, to my thinking he is over fond of keeping folks in straight jacket" (Child, 1829, p. 11). As time passes, Sally becomes engaged to another young man and Mary and Charles meet in secret and their love grows despite the fact that Mr. Conant doesn’t approve of Charles and his religious views. Mrs. Conant however can see that her daughter truly loves Charles, and assists them as far as her conscience will allow her. Mrs. Conant's illness has kept Mary from a great deal of things and this is her way of atoning for Mary's sacrifice. Charles wants to marry Mary and take her back to England where they can be happy, and where he won't be judged for keeping to the King's religion, but Mary won't leave while her mother is alive.

An Indian chief, Corbitant, attacks the settlement and Hobomok warns the Government of his plans. Corbitant is married to the woman Hobomok was engaged to, but he called off the wedding shortly after Mary had healed his sick mother. This has sparked a feeling in Hobomok, and it is clear he feels a sort of love for her, but at this time it is unclear what kind. "Mary had administered cordials to his sick mother, which restored her to life after the most skilful of their priests had pronounced her hopeless: and ever since that time, he had looked upon her with reverence, which almost amounted to adoration." (Child, 1829, p.19) This attack and Hobomok's meeting with Corbitant, as a translator, brings to attention two things; Hobomok holds love for Mary and shares her experience with a sick mother; and the aftermath of the attack has an effect on the female population. Mr. Conant is a man of authority and is deeply committed to the settlement's growth and people seem to turn to him. His wife experiences the same after the attack. The women come to her for comfort because their husbands won't tell them what is going on, and they end up comforting each other as a group, coming up with ideas of how to help the rest of the settlement after the attack. They gather under the strong religious figure of Mrs. Conant. This is not the last time this happens. Later the church in the settlement prospers, along with its industry and there are more families. This results in regular organization of the church, where women were active participants. Despite of their original job of keeping house, cooking and raising children, the women of the Puritan church seemed to crave more to do.

Mr. Conant and Mr. Brown are not on the best of terms, and with the prosperity of the church, which is Puritan, Mr. Conant gains more influence in the settlement. He does not agree with Charles' choice to be a member of the Episcopalian church, and he agrees even less with his quest to woo his daughter. Mr. Conant has him sent in exile and he boards a ship bound for India probably because he dreamed the next time he would set his feet on English soil, Mary would be his wife. Mary is heartbroken when they receive news that his ship has sunk and that he has died at sea. She hates her father for making Charles leave, she hates herself for not trying harder to change his mind, she hates the Puritan church for being so set in its ways. After her loss she has no regard for her father's opinion anymore and decides to marry Hobomok, believing in the ritual and his word that he has love for her. Mary's rebellious decisions are the consequences of her father's actions on behalf of his church. Mary is thus one of the few who take advantage of the possibilities for women to organize themselves and step into the social aspect of the world, through the church. The effect the church has had on her has pushed her as far away from her family as is possible. To marry someone who loves her, she must look outside the settlement's puritan population so find a remote satisfaction. Hobomok and Mary has a child (Hobomok Charles Conant) and Hobomok truly loves Mary. Her love for him started slow, but she reveals that it grows every day when she sees how kind he is, and how much he loves her and their son.

Charles returns to the settlement. It turns out he is alive and more intent than ever on marrying Mary. She is happy he is alive, but she is already married to Hobomok and cannot grant his quest. Upon seeing that Mary's true love lies with Charles, her husband tells her that he will divorce her, so she can marry him. Mary and Charles get married in the settlement due to Mrs. Conant's dying wish, which her husband couldn't refuse, and Charles raises Hobomok Jr. as his son in a white environment where his Indian heritage is neglected. The world wasn’t ready to define a mix-race marriage a happy ending just yet, but through the relationship, Child presented a lot of ideas that provoked, and was in keeping with the political agenda of her lifetime such as divorce, mix-race marriage, rebellion and solidarity among women.

James F. Cooper's "The Wept of Wish-ton-Wish"

The Wept of Wish-ton Wish, is also set in the 17th century and features a Puritan family and its value to the settlement of Wish-ton-Wish (which Cooper claimed was the Indian translation of Whippoorwill, a bird known for its sound). Captain Heathcote who was widowed when his wife died in childbirth, giving him a single son, Content Heathcote has moved from the prosperity of England and settled her in his older days. He brings Content and his wife Ruth Harding Heathcote to the New World with him and the family becomes esteemed in the settlement because of Captain Heathcote's Puritan ways, which gives him clarity even when face with difficult times. He is truly a man of God, kind and repenting and he never turns away those in need. Compared to the Puritan population in Child's Hobomok, the Puritan religion in this novel is interesting and seems to make people kind and likeable, whereas Mr. Conant and his associates proceed to talk about religion with deep seriousness while the plot of the novel happens around their conversations. Thus, these conversations seem more like a distraction from the plot than of actual use to it. (Sederholm, 2006) The settlement is visited by a stranger who speaks to Captain Heathcote in secret, appearing as a man of urgency and mystery at the same time. The stranger is later revealed to be one of the men responsible for the execution of Charles I, and they come to know him as Submission. Even though officials from England come to inquire about this man, Captain Heathcote does not give him up even though it is clear he knows the identity of the man and his actions. Another important character from outside the settlement is the 15-year old savage boy Conanchet, who is captured outside the settlement and held captive by Ruth and Content. They are trying to convert his savage ways into white-civilization and he spends a long time with the settlers. Even though Ruth and Content spend much time with him, however, it is the stranger Submission that connects with the boy. Conanchet eventually escapes, right before an attack on the settlement where many of the townspeople die. The Heathcote family manages to hide and elude death but at the price of Ruth, the young daughter of Content and Ruth who has disappeared. She is henceforth known as "the wept" because her disappearance shakes the remaining population into sorrow. Ruth is affected the most and spirals into depression and sickness.

Time is fast forwarded to a time where Wish-ton-Wish has been rebuilt and in 1675, the Indians strike the town again, Conanchet is now the leader of the Narragansets, and his tribe is organized under Metacom who has moved to unite all red men to annihilate the English settlers. When the last attack happened, Conanchet had seen the town burn and believed the Heathcote family had died and he feels conflicted when he is asked to kill them, after they have been captured in the new attack. It turns out that for all these years after he believed them to be killed in the former attack he had saved baby Ruth from the chaos. She has grown to be around 18 years, a white savage woman and Conanchet's wife. She has no memory of her life in white society and doesn’t recognize her mother, who is thrilled to see her. The Wept is now called Narra-mattah and she has given birth to a child which she proudly presents to her white family, but their reaction isn’t as filled with glee as she expected, even though her mother tries her best to be. The family who tried to turn the savage Conanchet into a white man has instead gained the opposite, a white daughter turned into a savage.

The end of the novel holds a clear message of social class as both Conanchet and Narra-mattah dies, leaving their infant child to be raised by the Heathcote family, as a white civilian. Conanchet dies how it is expected of him, as a strong Indian chief, and Narra-mattah's shock as she stands over his dead body brings back memories of her childhood as a Puritan. Her childhood memories combined with the values she has adopted later is too much for her and she dies next to her husband.

The death of Narra-mattah might seem a little strange. How can one die from conflicting values? In the case of Cooper this isn’t simply normal, but seemingly a rule. His characters are defined by their social class and is given a very simple purpose in order to achieve a happy ending; "Any character who accepts his or her position and fulfils his or her assigned role is rewarded." (Zeitvogel, 2004) This rule, and the opposing, that a character who tries to surpass his or her class or fails to fulfill that role is punished. This is Cooper's view of how American values should be, in action. This places him in opposition with Child, whose view of American values include strong women who dare to challenge the "old ways" in order to gain the possibility of vielding more power through a career, the possibility of owning land or divorcing a man without losing her entire livelihood and thus becoming a liability for her parents.

Cooper has been criticised for being to set in the old ways but in the Wept, he has allowed himself to present the power of women, but only in the confined setting of "the wilderness" of the settlement, and although he thus acknowledges that women can bear the responsibility of gaining more power, he still trusts the real power with men, who "control all social spaces, and political power" (Zeitvogel, 2004). Contrasted in Child's strong female characters, particularly Mary and Sally but also Mrs. Conant, this might not be as visible, but the power is there. Ruth is given the responsibility of educating a savage teen into a white man of standards, and given the proceedings of the novel, with two major attacks and general quarrels with the natives, this would be an important task. The advantage of having a savage on their side, or simply having him speak their language in order to function as a mediator would be priceless for the Puritans, as they wanted to avoid bloodshed, on both sides of the quarrels. If Cooper was too set in the old ways he wouldn’t have allowed Ruth to hold that kind of power. What is interesting is that Cooper's definition of good American values was rooted in traditional gender roles, but because of the social change he was exposed to in his later years, he implemented them in his novels even though he didn’t necessarily agree. This implementation was, however, bound to "the wilderness", of the early settlements and the nature around it.

The puritan church is a central factor in both of these novels, but as we have seen, to very different ends. Cooper's novel uses religion as an explanation for Captain Heathcote's goodness and thus his family's as well. To Cooper, Christianity serves as guidelines for a good life, and those of his characters who live their life according to it, and the other values he treasures in society get their happy ending. This in accordance to his "rules" where a character who realizes and accepts their role in life and society is rewarded. However, we can argue that Captain Heathcote, who is portrayed as a good man and a good Christian is punished at the end of the novel despite of his goodness. In the span of one day, he is exposed for having harboured a fugitive from the law, loses his grandchild Narra-mattah and her husband, whom he knew as a boy. The question here is what the reader perceives as a punishment. Is Canonchet and Narra-mattah's deaths only a punishment for them? Isn’t it also a form of punishment of Content, the Captain and Ruth who are left behind? And what of the child, is it fair to have it punished because it is mix-raced even though it is only an infant? The bottom line of all of this is that throughout the novel, Captain Heathcote has had absolute faith in his religion and led his family and community through hardships, giving the Puritan church an important place as a positive factor in the novel.

Child in on the other hand presents a puritan church that is tedious, repetitive and sometimes destructive. The antebellum philosophy of the 19th century was that women had to take their work outside the house. What good were their roles as the person who raised the children if they had no control over what they did outside of the house? This kind of thinking made opportunities to become active in social setting, which was a breach of the old gender roles. Child, who was an abolitionist and women's rights activist, plays on this when she organizes the women of her settlement in the 1600rds. Through the Puritan form of Christianity, which is known for its settled gender roles and rules of conduct, the women in Hobomok leave their houses to participate in the social life. Looking at the church in this manner might prompt us to say that it created good opportunities for women; but Child has another message about the church as well. The church creates problems for Mary and Charles' love, and even though he would if he could, Charles believes he could in no situation become a Puritan – something that becomes clearer to him the longer he spends in the settlement. His interests are pulled between the girl he loves and his religious beliefs. His brother Samuel Brown tells him; "I could hardly stoop to woo the daughter of that dogmatic rascal" Though I will acknowledge, she is the very queen of women" (Child, 1824, p.38). this sentence reflects the entirety of Charles' struggle, and it gets in his way throughout the rest of his time in the settlement.

The choice to work within this era seems to be connected to Child and Cooper's political wish to present what they considered the correct "all-American values". To do this, they have worked within the early settlements of America in order to play off of the confined society of an early settlement. The people there know each other, they mostly share the same religion, and they all have doubts about the native savages that lives on the same land as them. Child has taken advantage of the hardships of a small community, heavily influenced by Puritan values, creating strong female characters that represents what women can do. Cooper has also given women more power within the borders of the tiny society of Wish-to-Wish. In this sense, he has managed to portray the values he feels should be universal to all Americans, while also exploring the arguments made by abolitionists and feminists of his time. The use of Puritan religion works to their advantage, even though they portray it very differently. Child as a hindrance and disruptive force, and Cooper as the base for a person's goodness and understanding of one's social class. We can thus conclude that the age of Puritans, settlers and early America has served its purpose as an agent to promote what the two authors feel should be the "all-American" values and their take on their contemporary society's debates about women's rights and gender roles, as well as race and rules of conduct.

Works cited:

Child, L. M (1824) Hobomok. Blackmask Online (2001) Retrieved: 29.09.17, from http://www.public-library.uk/ebooks/45/90.pdf

Cooper, J. F. (1866) The Wept of Wish-ton-Wish: A Tale. Stringer & Townsend. Retrieved: 29.09.17, from http://www.gasl.org/refbib/Cooper__Wish_Ton_Wish.pdf

Dekker, G. G. (1998, ed. 2016) James Fenimore Cooper: American Author. Retrieved: 11.12.17, from Encyclopædia Brittannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Fenimore-Cooper

Editors of Encyclopædia Brittannica (1998, ed. 2017) Lydia Maria Child: American Author. Retrieved: 11.12.17, from Encyclopædia Brittannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lydia-Maria-Child

Editors of Encyclopædia Brittannica (1998) Knickerbocker School: American Literature. Retrieved: 11.12.17, from Encyclopædia Brittannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Knickerbocker-school

Johannessen, L. (2009, ed. 2017) Lydia Maria Child. Retrieved: 11.12.17, from Store Norske Leksikon, https://snl.no/Lydia_Maria_Child

Sederholm, C. H. (2006) Dividing Religion from Theology in Lydia Maria Child's Hobomok. Retrieved: 10.10.17, from The American Transcendental Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 3, https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-154561988/dividing-religion-from-theology-in-lydia-maria-child-s

Walters, R. G. (1978) American Reformers: 1815-1860. Farrar, Straus & Girouz.

Zeitvogel, C. (2004) Gender Power and Social Class: The Role of Women in James Fenimore Cooper's "The Pathfinder", "Homeward Bound", "Home as Found", and "The Ways of the Hour". Retrieved: 03.10.17, from The Cooper Society Website (2005), http://external.oneonta.edu/cooper/articles/other/2004other-zeitvogel.html#note

Øverland, O. (2009, ed. 2017) James Fenimore Cooper. Retrieved 11.12.17, from Store Norske Leksikon, https://snl.no/James_Fenimore_Cooper