Land of Invented Languages

I recently read a book published earlier this year: In the Land of Invented Languages, by Arika Okrent (Spiegel & Grau, New York 2009).

In general, there seems to be two main attitudes to "artificial" languages, like Esperanto: the extremely enthusiastic, and the extremely sceptical.

(I put "artificial" within inverted commas, because all human languages are artificial, especially their written forms. Writing and books are no natural phenomena, and spelling norms are often decided by political bodies; that may be the reason why English has at least two: the British and the US:ian. The term currently most used by those who know is "planned languages".)

Some are deeply engaged in one of these languages, believe it will save the world, and that everything created in it is just wonderful.

Others are not, don't think they have any value at all, and believe that a planned language can't be a living one.

Neither attitude is quite in accordance with facts. Still, many professional linguists belong to the second school, without having actually explored the matter.

A funny thing with Esperanto is that anyone can have a very strong opinion about it, whether he knows anything about it or not. Linguists wouldn't do so with Latin, Sanskrit, or Spanish, but many of them don't hesitate to do it with Esperanto.

Okrent, however, is a professional linguist who has managed to practice a more scholarly attitude and find some kind of golden means. She is not an active member of the Esperanto movement, or of any similar movement around some other planned language, but she takes the matter seriously, and she has cared to do some field study before making her conclusions. She has taken a good look at several planned languages, and has visited conventions of both Esperanto and Klingon speakers.

This makes her rare indeed.

Okrent started out with the prejudiced idea that planned languages can’t be living tongues, but her experiences taught her better.

The field of "invented" languages, as Okrent prefers to call them, is vast indeed; even if discarding languages like Pali and Jaina Prakrit (standardised and possibly more or less planned Middle Indian languages used for the oldest canons of Buddhism and Jainism, respectively), the history of planned languages goes at least as far back as Hildegard of Bingen, a German abbess living 1098-1179. She left, among her papers, a glossary of about a thousand words in something she called Lingua Ignota, "Unknown Language", with translations into Latin and sometimes into German. No one has the slightest idea why she made it, and how she intended to use it.

Okrent has concentrated at a few high-lights of the more than nine hundred projects she has found, from Lingua Ignota and onwards: Wilkins’ logical language from the 17th century, Esperanto from the 19th but still very much in use, and from the 20th century Charles Bliss’ symbolical language, as well as Logban and its offshoot Lojban as more a less a return to Wilkins’ ideas of a perfectly logical language, and finally Klingon.

She is rather short about languages with similar goals as Esperanto, like Volapük that was defeated by it, or Ido and Interlingua which failed to defeat it. She is also rather short about the languages connected to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, although at least Sindarin may actually have about as many fans as Klingon.

Her inclusion of both Esperanto and Klingon shows the widely different intentions of the language-creator wannabees (or "initiators", as the initiatior of Esperanto, LL Zamenhof, modestly preferred to call himself, being aware that a living language is never a single man's creation, although its basis may be so):

Some planned languages, like Esperanto, were launched to be actually used for all aspects of human life (Esperanto was never intended to be just an "auxiliary" language).

Others, like Sindarin and Klingon, started out just for the fun of it, and got a circle of fans by being used in books or films.

Still others, like Wilkins' early project, was meant to make it easier for philosophers to think logically; Medieval Latin was not felt by some to be good enough for that purpose, although it did work quite well as a neutral and international language.

In the list of 500 ”invented languages” at the end of the book, Okrent includes Anglic, which actually is just ordinary English with a revised spelling, not a language in its own right (she might as well have included George Bernhard Shaw’s proposed spelling reform), and Basic English, which also is hardly a language of its own – just plain English with a limited word-stock. On the other hand, I don't find any mention of Latino sine flexione, which differs more from ordinary Latin than Anglic or Basic from English.

Okrent makes it clear that a planned language, same as less planned ones (which she mistakenly insists on calling "natural languages"), can only survive if it is used by a community; which may explain why Esperanto is still thriving, while Ido and Interlingua have difficulties to survive, and Volapük is dead.

Regarding the so-called "natural" languages, Okrent's view is not realistic. She writes, at p. 4-5:

"The languages we speak were not created according to any plan or design. Who invented French? Who invented Portuguese? No one. They just happened. They arose."

That may be almost true for spoken dialects, but not for any written language, if it has any kind of spelling norms or formal grammatical rules. Present day official French is the creation of the French Academy. Modern official Italian was largely created by Dante, who based his written Italian on his own spoken dialect - upper class Tuscanian.

An extreme case is modern Norwegian, one language with two alternative norms for its written form, and with a number of spoken dialects which some say is identical with the number of Norwegians. Both forms of written Norwegian are very much planned.

A language used in two or more countries may have several official norms - British English differs from American English, but official British English is very much an "acquired" language taught in schools to pupils, who often grew up speaking not quite that form of the language.

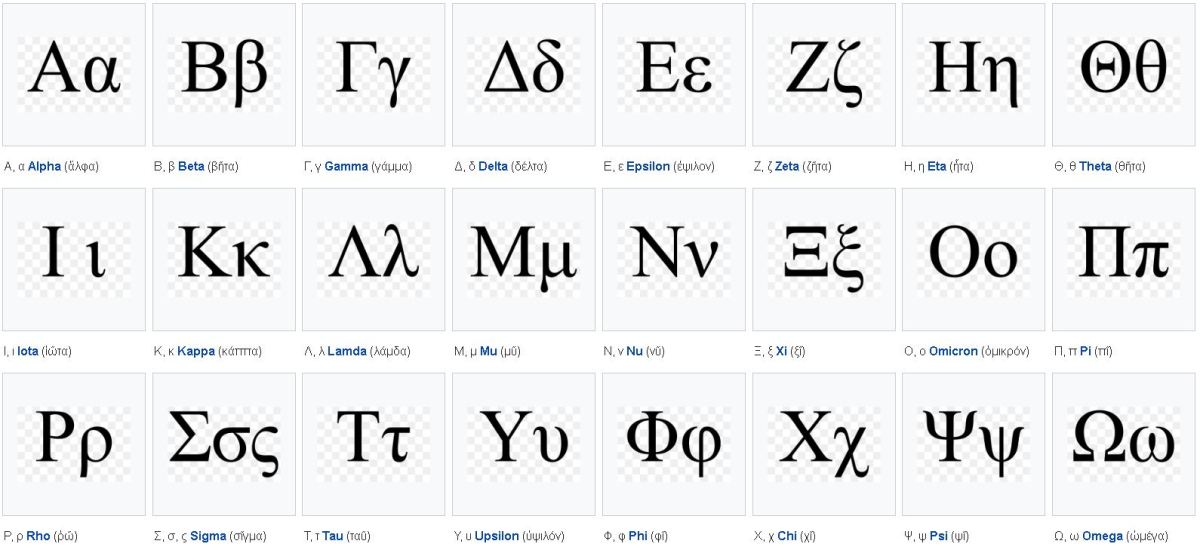

Why was ancient Greek written in several dialects, but ancient Latin only in one? Because the Romans founded a centralised empire, while the Greek mostly lived in several mutually independent city-states; so there was a political power behind Latin uniformity. Official Latin did not "just happen".

Actually, the difference between a normalized "natural" language and an "aposteriorical" planned language - i. e. a planned language based on one or several languages already existing - is much smaller than the difference between the latter and an "apriorical" planned language, i. e. a language created from scratch (and normally still-born). Esperanto is more similar to Latin than to Loglan.

There are some aspects of invented language history which haven't found a place in Okrent's book, e. g. the history of the Workers' Esperanto Movement, or the fact that Esperanto has sometimes been branded as "the dangerous language" by people like Hitler, Stalin, and some Obama haters in our time.

But there are limits to what you can get into about 350 pages.