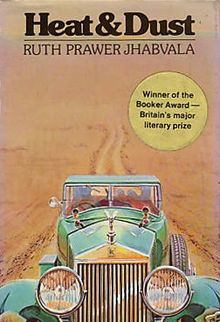

Literature and its Workings- "Heat and Dust" by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

What is storytelling? Some might select it as the basis of history, while others might hail it as the basis of life. It is the most unique form of art in that it its genres include every form of art ever invented, from painting and drawing to photography, music, film, and finally, literature. Storytelling is, to put it simply, the definition of art.

As humans, we need storytelling to survive. We need its lessons and entertainment. Without it, the world is nothing but a repeat of past mistakes and a sea of miserable and lonely people. However, that isn’t to say that everyone likes all of the genres equally.

Paintings and drawings allows for artists to produce images of the world as they see it, while photography permits the capturing of stills of those moments that should last forever. Vocal music is a personal journey of release in which the musician allows the world to know their deepest emotions, while instrumentals allow for creative interpretation of the musician’s thoughts. Film and acting lets actors and actresses escape from whatever hardships that may be present in their lives to go away for months while they become somebody else and solve that person’s problem. Writing literature lets the author release to a select few a story that they are proud of, just because they created it.

What makes storytelling so valuable, though, is that everybody has the ability, but not the will. Everybody who has ever learned how to read and write words, in any language, can write a bestseller and anybody who knows how to hold a pencil, pen, or paintbrush can draw or paint the next great masterpiece. You just have to be willing to not only try, but dedicate yourself. Not everybody, however, will do that part, so it’s only fitting that we honor those who will by showing attention to their work.

For a painter, drawer, or photographer to draw me in, they must have something in their work that no one else has. There must be something unique or catchy in the look or meaning of their picture to make me want to even consider hanging it up on my wall. Films and works of literature must have a plot twist. There must be something that I did not see coming, because if I know what’s going to happen, then what’s the use in reading or watching? However, there are two exceptions to that preference. The first is a suspense element. If there is no twist or if the twist is easy to figure out beforehand, then it or the story should be so tense that my body goes completely stiff from staying curled up for so long.

The second exception is an idea. If the story presents an idea for me to think about (it could be one I have or have not thought about before), then I’m satisfied. However, it has to be a deep thinking, heavy idea. It can’t be simple or elementary.

In Heat and Dust, Jhabvala shows the superiority of the British in both eras by giving the reader a before and after, or then and now, look at their happenings in India. In Olivia’s time, they ruled the country and criticized the Indians and their culture, viewing their ways as “plain savagery and barbarism” (pg. 59). In the granddaughter’s time, the British were arrogant enough to go to India as tourists who thought themselves unbreakable, only to wind up crowding up the sidewalk outside of a hotel, looking “a derelict lot” (pg. 5). In both of these instances, the British went into India with a pompous attitude, only they weren’t so lucky the second time around.

Jhabvala doesn’t separate these attitudes from the story, but instead use them to drive it. Olivia begins to, in her own way, reject British beliefs in favor of Indian ones, even saying that “‘[she’d] be grateful for such a custom’” (pg. 60) as the suttee. One has to wonder, though, about the real reason she spoke out. Did she feel sorry for the woman because of the way she was being criticized or did she truly believe what she said? It’s probably the first possibility, as she didn’t speak up until her “challenge” (pg. 60) to Douglas’ agreement with Mr. Crawford that the suttee lady was not “an altogether willing participant” (pg. 60) in her own death. She felt so sorry for the woman that in that instance, she saw herself in the lady’s shoes, and was perfectly content with the way they fit.

The granddaughter knew that she “had to submit to all the social rules they thought fit to apply to [her] case” (pg. 8), or else she’d end up like the lot of Europeans on the sidewalk outside of A’s, so she became accustomed to Indian life. However, you have to ask: did she do it out of necessity to survive, fear of the inverse, or a want to fit in. It was probably a mixture of all three. She knew that if she didn’t, she wouldn’t get anywhere in the country, as she’d seen with her own eyes. What she saw outside of A’s was a group of people who looked “like souls in hell” (pg. 6), which is enough to terrify anyone onto the right path. The granddaughter would want to fit in because India is “‘[for] Indians only’” (pg. 159), and when you’re in India, you’re either one-hundred percent India, or one-hundred percent outcast.

Jhabvala shows the impact of the Indian culture on the women’s western sensibilities by taking the reader through their lives in India and showing how and in what ways India changes them.

Olivia was probably used to the fanciness and higher class of Britain before coming to India, which would explain why she “was already beginning to get bored” (pg. 14) after several months as a foreigner. When Olivia went to the Nawab’s palace for the first time, her eyes “lit up” (pg. 15) because she was being reintroduced to luxury. The most probable reason “she liked it” (pg. 17) when he started giving her attention because she was unsatisfied with her marriage. After all, “Douglas got up at the crack of dawn… and was usually too rushed to come home again till late in the evening and then always with files” (pg. 17). So, it’s not hard to see why Olivia would go outside her marriage, no matter how “noble and fair” (pg. 16) Douglas was. However, in the end, India might’ve destroyed Olivia. Where in England, everything, her marriage and her life, was perfect, when her experience in India was over, she’d cheated on her husband and gotten pregnant, had an abortion, and finally, ran off with a married man and “stayed in the house in the mountains he had bought for her” (pg. 172-173), without him most of the time.

The granddaughter came to India completely neutral. She just wanted to follow the story of her grandfather’s first wife, who just so happened to run off with a married Indian prince. When she first arrived, she was clueless about India and its workings, as the woman at the S.M. Hostel pointed out from her being “so careless” (pg. 3) about her belongings. She smoothly transformed into an Indian by living with Inder Lal and befriending him and his mother. She allowed herself to truly experience India in a way that Olivia didn’t. After she got pregnant, she assured Maji that she “was not running away but on the contrary was going further” (pg. 173). She chooses not to run away because she knows that there is nothing to run away from. India is not a bad place if you not only look for the good, but do it for non-selfish reasons.

Olivia’s western sensibilities were her downfall in India because she tried to transfer them over. The granddaughter, on the other hand, had no western sensibilities to clash with the Indian culture, which made her transition to and life in India easier.

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

Movie Poster