- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- Literary Criticism & Theory

Lord Byron's Darkness

Lord Byron’s “Darkness”

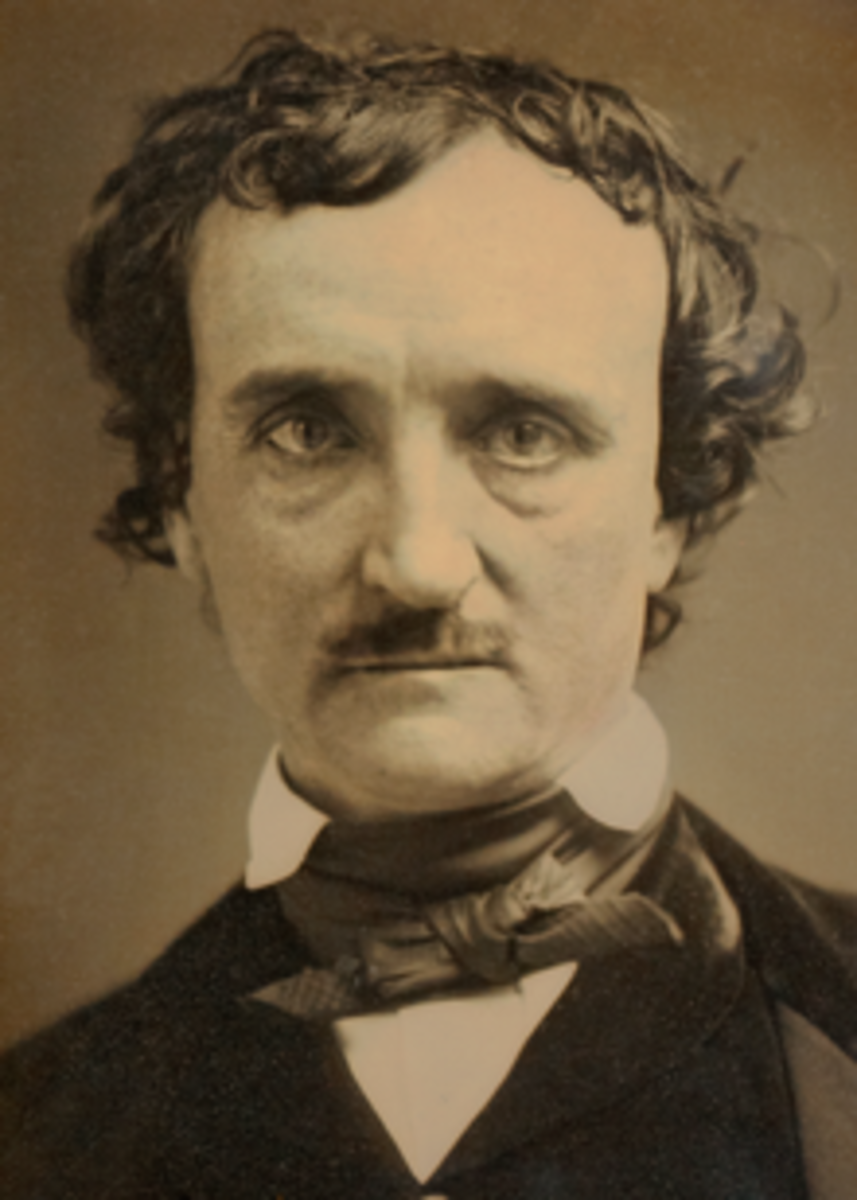

In his poem “Darkness” Lord Byron gives an apocalyptic view of the world, as he pictured it was in 1816. Through the relation of his first person speaker, using sublime imagery, which gives hints to the author’s emotional state of mind at the time, “Darkness” seems to have been written as a satirical account of what might have been the public’s hysteria during that “Summer of Darkness.” Byron takes advantage of the events of the time, and creates a hellish description of the end of humanity. Around Europe, at the time, fanaticism was growing as fear of the end of the world was raised by false prophesies and misinterpretations of natural occurrences. While the worst was yet to come from the effects of a natural disaster, Byron took the opportunity to liken the events to something resembling the reaction of the Israelites when Moses took too long to come down from Mt. Sinai.

The year 1816 saw Byron estranged from his home country, as well as his marriage to Anne Isabella Milbanke, the first of which was self-imposed. While Byron had a reputation as a lothario, one would have to presume that the vanity, or at least, its consequences, he was noted for had taken an emotional toll on him. The year was also the year after the eruption of Mt. Tambora in Indonesia. The cloud of volcanic ash from the eruption reached Europe that summer affecting crops and livestock, causing over 200,000 deaths through famine and disease.

The poem starts out with the speaker proclaiming, “I had a dream, which was not at all a dream./the bright sun was extinguished…” (1-2).

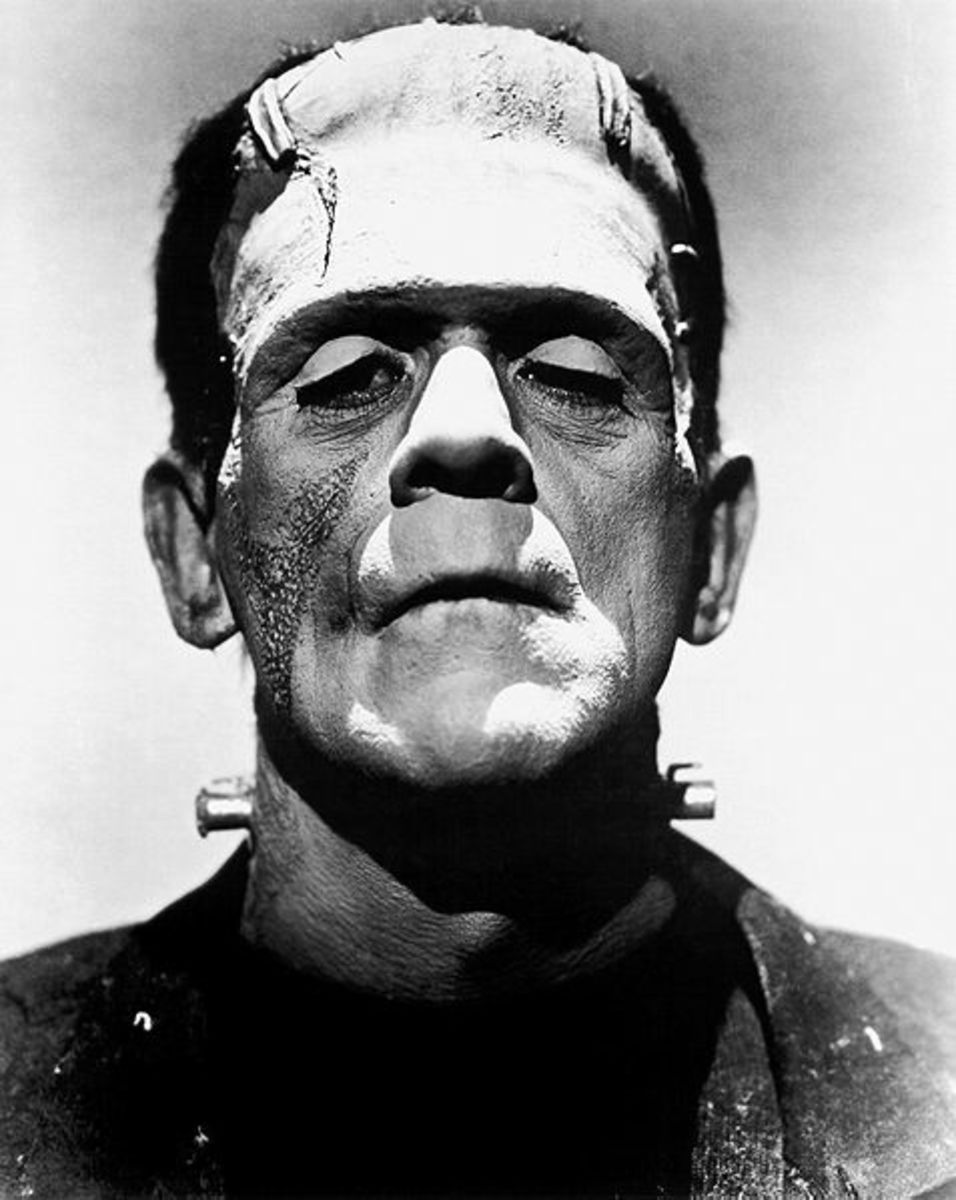

Byron, along with Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, spent that summer in Switzerland where the darkness prompted him to challenge his friends to write their own macabre stories, In Switzerland, the damp and dark year of 1816 stimulated Gothic imaginings that still entertains. Vacationing near Lake Geneva that summer, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and his soon-to-be wife, Mary Wollstonecraft, and some friends sat out a June storm reading a collection of German ghost stories. (Evans) From these stories came Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” John Polidori’s “The Vampyre,” as well as Byron’s “Darkness.”

It is with this challenge that Byron seems to make a social satire of the catastrophic events of the time. Europe was in a cloud of darkness, and he chose to offer a more neo-classical, if you will, interpretation of the effect. This is not to say that he could have foreseen the effects outcome, it is just that he paints an extreme picture in a grotesque version of what very well might have been going through the heads of a superstitious community at the time. While most of Europe was going through a kind of “Hell,” he, and his fellow intellectuals were on a vacation, upset over the inability to procure a vessel for their sailing exposition.

Descriptions given throughout the beginning of the poem relate the actual occurrences of the day, in a 2006 Atlantis Journal article Bill Phillips states, "When Byron wrote that 'Morn came and went – and came, and brought no day' far from being metaphorical, he was referring to the day to day reality of millions of people across the northern hemisphere at that time." Keats’s ‘To Autumn’ on the other hand, which was written in September 1819, celebrates the fact that the previous three years of appalling weather and failed harvests had finally come to an end. (Phillips)

In the article, Phillips relates Mary Shelley’s accounts to her writing of “Frankenstein,” and the summer spent with Byron at the Villa Diodati. While darkness blanketed northern Europe, Shelley and Byron were disappointed that the weather had prevented them from boating on Lake Geneva, and sending up a balloon, here, once again the neo-classical and aristocratic values seem to present themselves. Byron at this time is still, even after his disgrace in England, what might be considered by today’s standards, an intellectual snob.

In line 17 of the poem, Byron references “volcanos,” and “forests set on fire,” an indication that he had knowledge of the cause for the conditions of the time. He uses this to set up his condemnation of mankind. He goes on to depict men as animals, driving themselves to the darkness:

The meager by the meager were devoured,

Even dogs assail’d their masters, all save one,

And he was faithful to a corse, and kept

The birds and beasts and famished men at bay,

Till hunger clung them, or the dropping dead. (46-50)

Byron paints a picture of humanity either dead or dying in a scene reminiscent of Milton’s Hell. He emphasizes man’s inferior qualities by placing a heroic accent to a dog protecting his dead master’s corpse. Images of: /men howling, birds shrieking, and vipers crawling/ are given to the reader, while the use of enjambment and scattered punctuation add a sense of urgency to the changed rhythm of the poem at this point.

At the end of the poem, Byron goes back to the less wild, iambic rhythm with which the poem starts out. The use of alliteration and consonance create a more even flow towards the ending of the poem, / The populous and the powerful-was a lump, / Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless-/ (70-71). Here Byron creates a calmer, more serene world. Darkness has taken control. The seas are calm, the winds are withered, and the clouds are gone. Man is gone, and no longer interfering with the natural order, the universe has returned to chaos. Byron shows contempt for humanity here, implying that it was man who created the disharmony in the universe to begin with.

While “Darkness” was written during the peak of the Romantic age, by one who would become known as one of the greatest Romantic writers, one cannot help but notice the anti-romantic tone of the poem. Unlike in earlier works, such as “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,” and later works, such as “Manfred,” the lack of the Byronic Hero is obvious. The speaker seems only to be relating, “A dream, which was not all a dream,” (1) with no hint towards emotion beyond the work’s romantic “I” at its very beginning. While most works of the time give indications of self-conscious reactions against the Neo-Classical form, Byron, in “Darkness,” seems to embrace it. Where as most Romantic works, such as: William Wordsworth’s “Tinturn Abbey” praise nature, Byron opts to show its more ferocious side. With haunting imagery reminiscent of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” Byron’s ending is not so forgiving. The conclusion of “Darkness” offers nothing but death and desolation.

“Darkness” presents itself to reflect the author’s emotional state at the time of its writing. This, according to a reference from Norton’s Anthology online, was Byron’s intention,

He seems to have identified his character with his writings; his poetry, at least a considerable portion of it, is a mirror in which are reflected the movements of his soul. He has even obtruded the events of his life upon public notice; he has solicited regard to the dark current of his sorrows; he has revealed the privacy of his domestic life, and demanded the public judgment of his character (Norton).

Unlike most poetry, where the reader is urged to disassociate the speaker from the author, Byron, at times, begs the opposite.

“Darkness” illustrates the emotional workings of a complex megalomaniac during a time of crisis in the world he lived. He fed off the public reaction and religious fervor that caused riots throughout Europe when it was thought that “Judgment Day” was at hand. He left himself open to scrutiny by depicting humanity for how he viewed it, a superstitious, self-serving, collection of beasts with the capabilities of reason and emotion, but the inability to use them. Through “Darkness,” Byron demonstrates the foolishness of man’s self-importance when placed against the backdrop of the most powerful of forces… nature itself.

Citations

Evans, Robert. "BLAST FROM THE PAST." Smithsonian 33.4 (2002): 52-57. Historical

Abstracts. EBSCO. Web. 3 Mar. 2010.

Gordon, George. Lord Byron. “Darkness,” Norton Anthology of English Literature Eighth

Edition, Volume D. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. W.W.Norton& Co, New York. (p. 614-616)

Print.

Hudson , Dale. "Romantic Period, Topics ". Norton Anthology of English Literature . 3/6/10

<http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/romantic/welcome.htm>