Machines Like Me: Ian McEwan Attempts a Twist on an Old Trope

Picture 1982 in a fashion that we least expect. The British lost the Falklands to Argentina. Alan Turing, John Lennon, and John F. Kennedy are all alive. Unemployment soars in epidemic proportions and cars are self-driving. Welcome to the Blade Runner vision of Ian McEwan in Machines Like Me. In his latest book, an alternate 1982 becomes the setting of Great Britain in her waning years. Like most speculative fiction that touches on future social ills, this book sets the bar as much as how Philip K. Dick envisions a technocratic future. Charlie Friend, the main protagonist, narrates all these social and political backdrop while wasting his existence through wrong choices and mismanaging whatever money he has left: “Whenever money came my way, I caused it to disappear, made a magic bonfire of it, stuffed it into a top hat and pulled out a turkey.”

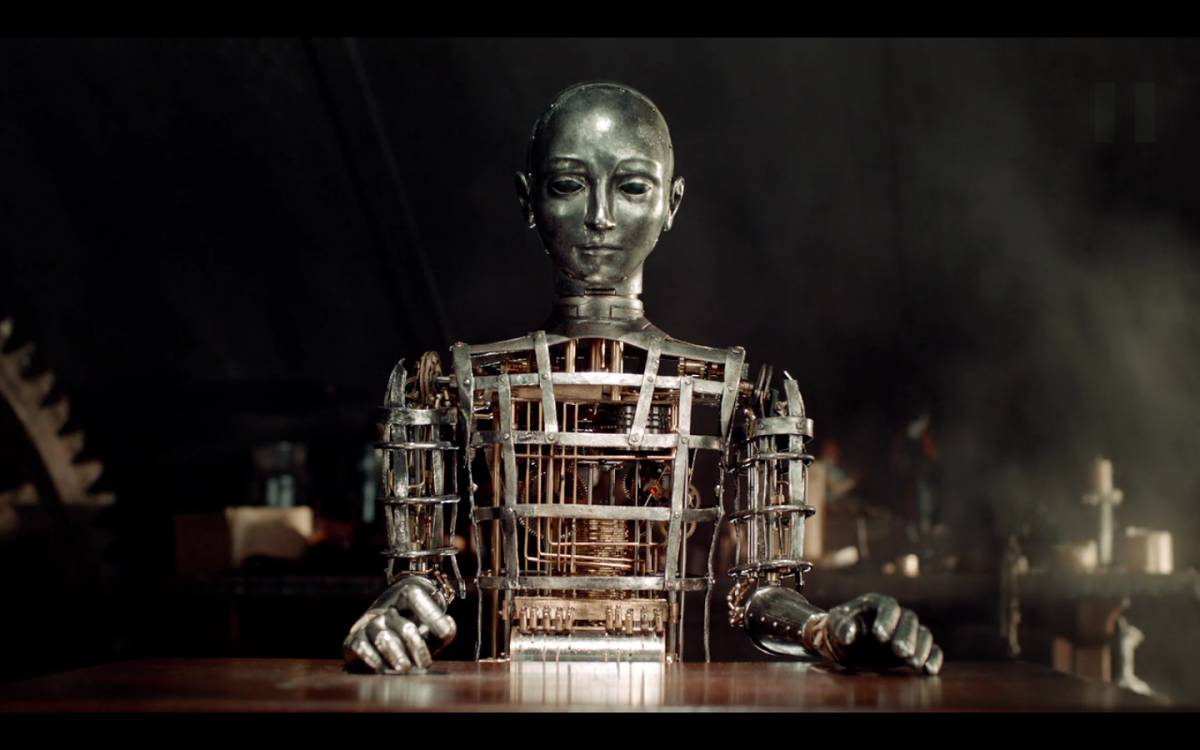

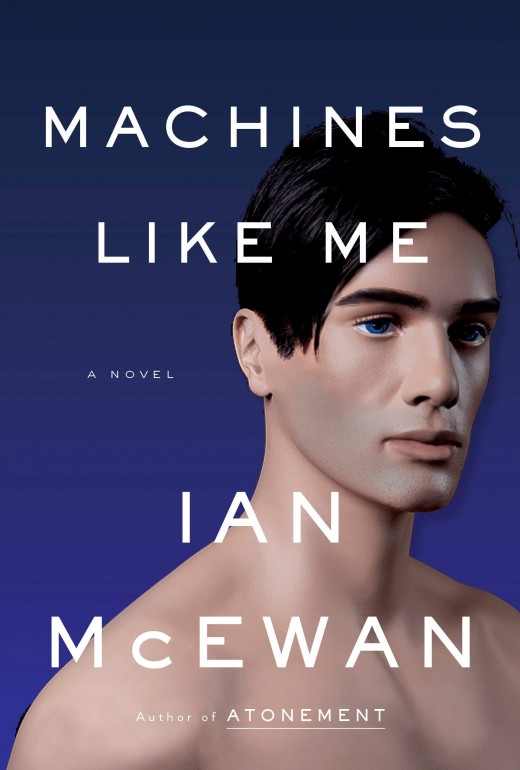

Thirty-two-year-old Charlie is a solitary stock market player operating in his small flat in South London using an obsolete P.C. model. Without much success at trading, he manages to make both ends meet through an inheritance from his mother. He goes through the story narration in a combination of laments, extolments, and cynical analysis of his worth. At times he is hopeful and recounts with fascination how he got hold of an extraordinary automaton commercially known as Adam, procured through the sum his mother had bequeathed him. Adam’s price was prohibitive. Charlie wanted an Eve, but the female automatons have sold out. How Mr. McEwan describes Adam is symptomatic that the automaton is bound to play an integral part in the plot: “Before us sat the ultimate plaything, the dream of ages, the triumph of humanism--or its angel of death. Exciting beyond measure, but frustrating too.”

The eerie scene of Charlie getting acquainted with Adam is similarly symptomatic of a tragic vein the plot traces. Charlie does not immediately charge Adam’s battery. The automaton’s user manual advises owners to take their time and study how to pre-set their companions. This scene takes the time to deconstruct Adam’s anatomy and what makes him distinct as a character. It conveys the modern equivalent of assembling your P.C. and taking time to find out what components work and what doesn’t. Fully charged, Adam’s awakening comes like the birth of a human child, where Charlie gives him time to assimilate information.

Charlie considers Adam as a sizeable investment in helping improve his quality of life. He has grand schemes for Adam, and one huge part of it is to use Adam to pursue Miranda, his upstairs neighbor whom Charlie has long been drawn to. Charlie does not have the audacity to express his true feelings for Miranda, who is ten years younger and pursuing a doctorate in social history. Charlie has high hopes that Miranda would consent to quasi-conjugal ownership of Adam. The care and maintenance of the automaton would draw them closer together. His rationale for the robot’s purchase then gets off the hook, even if he does not consider any ramifications.

Machines Like Me is doing what has long been done to the A.I conundrum. Speculative fiction under the pens of Philip K. Dick, Isaac Asimov, Dan Simmons, and William Gibson have discourses on the eschatology of tech and its incompatibility with human values and interests. It presupposes that the advancement of science and technology is how we are pushing ourselves toward self-destruction. Technology makes our lives easier, but to how far and to what extent are often questions addressed in the sci-fi genre. Charlie is up to his neck in financial troubles. Miranda has a dark past. Adam it appears is the character that serves as an antithesis to the clouded mores of his human masters. He is intellectually and physically advantaged, and his computational decisions take the well-being of everyone involved into account. Adam is a manifestation of irony as a servant that is superior to his masters. Despite this superiority, a human inclination for the natural persists, as Miranda expresses a biological interest in nurturing a real child.

And as a sophisticated robot capable of independent thought, Adam demands freedom and rebels in the process. Primarily because he has a higher moral compass than his human counterparts, and is subject to Asimov’s Law of Robotics. Behind Adam’s crusade is Charlie’s suspicion of Miranda and Adam’s betrayal taking place behind the sanctity of the bedroom. Charlie’s original plans for Miranda to assume a maternal role for Adam backfires as she finds the well-endowed automaton far more sexually gratifying than Charlie.

Adam is the most noteworthy character in the book, with his constantly intense presence and edifying scruples. He is designed to meet the highest standards in A.I. technology and represent the best service to humankind: “He was advertised as a companion, an intellectual sparring partner, friend, and factotum who could wash dishes, make beds and ‘think.’” But his design takes an extra mile as implied in his amorous features that he can tend to carnal recreations. He reads and educates himself, and argues with the most unconventional ideas that make sense, particularly when he predicts the obsolescence and ultimately the death of literature since it is an art that reflects a variety of human failures.

Machines Like Me drum-rolls the ramifications of A.I. as an indispensable yet still limited tool that then becomes antithetical to its original intent--as a partner in progress. It becomes an extension of human flaws and errors stemming from disagreements, risks, and faulty decisions. Our baser instincts and propensity for destruction will always go side by side with innovation. Mr. McEwan is suggesting left-wing politics for Britain, with Tony Benn in his refusal to have another referendum and challenging Margaret Thatcher for the position of prime minister. The novel does an excellent service of opening millennials to a stark future wherein humans are losing jobs to robots. There will be more free time for people, but at what cost?

Still, Mr. McEwan has done what eminent science fiction writers have done in the past, rendering the novel a clichéd attempt to overhaul a theme by presenting it with moral and social ambiguities. That a robot operating for the welfare of humans is nothing new. This also strikes a familiar illustration that excessive moral righteousness that we impose upon others and encode on our creation can be counterproductive. Either way, if Mr. McEwan projected Adam as a cold-blooded killing machine, it is at best, another cliché.

We cannot blame the book for delving into a familiar and overdone territory, but the problem arises that it does not offer anything new to deviate from the standard sci-fi trope. While it depicts human-like robots in their 244 degrees of freedom, their feasibility towards coital activity could have been an issue worthy of deeper addressing. If robots are subject to Asimov’s Six Laws of Robotics, could they also operate under laws governing them to sexual norms? Their right to autonomy is a similar question that presses for an answer.

Similarly, Charlie’s introspections about the past, present, and future are typical discourses on man’s existential crisis and how our excesses aggravate our impending decay. When he says, “We create a machine with intelligence and self-awareness and push it out into our imperfect world. Devised along generally rational lines, well disposed to others, such a mind soon finds itself in a hurricane of contradictions. We’ve lived with them and the list wearies us.” It is an invitation to embrace a deterministic future where there is no escape.

Machines Like Me is not that disappointing. It does have fascinating and thought-provoking moments. But such moments do not linger after you close the book, and it leaves you feeling so-so.