- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- Literary Criticism & Theory

Madness and Melancholy: Abnormal Psychology in the Works of Charlotte Brontë (The Professor) Part II

It is advised that you read Part I first, for it provides essential background to its successors.

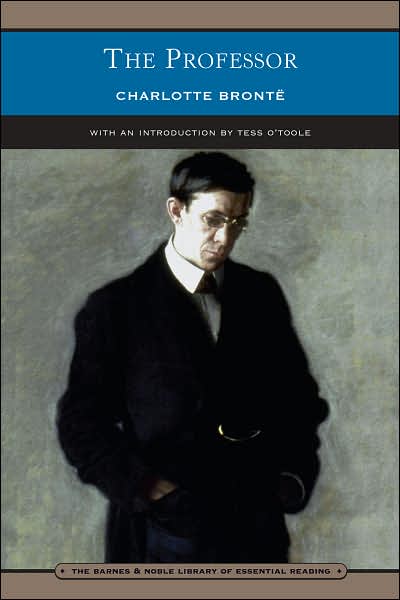

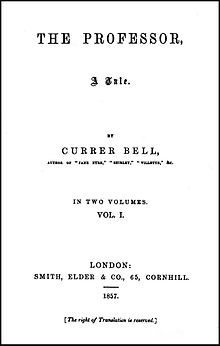

The Professor was the first book written by Charlotte Brontë but the last published after six failed attempts (Howells 160), and is described by Michael S. Kearns as “a study in unendearing self-control” (142). It is vastly different from Brontë’s other books in many ways. The main character and narrator is male, and his character is generally not very well accepted by readers, as he is considered “a man who understands little of other people and who seems to know nothing of the unseen seat of Life” (Kearns 143). While being able to see into a character’s mind and delve into their thoughts is generally a good thing, William Crimsworth’s mind is not a very attractive place to be, for he “never allows himself any extremity of feeling. The passions of rapture and despair only impinge on his life through the agency of the young lace-mender, Frances, whom he comes to love” (Kearns 142). Lawrence J. Starzyk suggests that Crimsworth distances himself from his emotions because he is “fearful of revealing his true self” (155), and this emotional evasion “is a psychological defense” (150), perhaps against his own depression. Because of Crimsworth’s tendency towards stoicism, after the rare moments that he does act spontaneously and allows himself to feel, he finds himself out of sorts and, in a way, separated from himself in a strange bout of what he calls “hypochondria” (The Professor 253).

The time of depression and withdrawal that Crimsworth experiences after his engagement to Frances could be seen as a temporary loss of self as he struggles to come to terms with the odd impulsiveness and burst of feelings that he has always steered away from, and it is a prime example of the concept of selfhood spoken of by Vrettos as part of the late Victorian era’s more modern study of psychology.

Crimsworth's Hypochondria from Boyhood

Crimsworth’s hypochondria is not a new experience for him, for he describes how he had fallen prey to “her” before, and he refers to it as having been “my acquaintance, nay, my guest, once before in boyhood” (The Professor 253). The Professor is not a Bildungsroman, as it is not Crimsworth’s coming of age story, but the reader is still allowed access to a few vague glimpses of his childhood through his narration. Despite the limited knowledge presented to the reader of Crimsworth’s childhood, it is obvious that Crimsworth does fit the criteria for the basic theme given by McCurdy: Crimsworth suffered in his youth from a “relative absence of any personal origins” (Starzyk 150).

He is an orphaned young man who is trying to find himself and love in the world, and his difficult background contributes to the man he is in the novel, with all of his evasiveness, stoicism, and reluctance to associate himself with spontaneous surges of emotion in order to save himself from the ever-encroaching depression. Crimsworth himself realizes that hypochondria had chosen him because of his difficult, lonely childhood when he says, “But my boyhood was lonely, parentless; uncheered by brother or sister; and there was no marvel that, just as I rose to youth, a sorceress [hypochondria], finding me lost in vague mental wanderings, with many affections and few objects, glowing aspirations and gloomy prospects, strong desires and slender hopes, should . . . lure me to her vaulted home of horrors” (The Professor 253). Even in her first novel, Charlotte Brontë was able to present the concept of selfhood and psychological development based on childhood experiences.

When depression steals upon him again after his engagement to Frances, Crimsworth wonders at hypochondria’s sudden reemergence in his life, reflecting that it was not surprising when it afflicted him in the past and marveling at its rearing its head “now, when my course was widening, my prospect brightening; when my affections had found a rest; when my desires, folding wings, weary with long flight, had just alighted on the very lap of fruition, and nestled there warm, content, under the caress of a soft hand” (253-254). There is no real explanation offered within the text, but it is possible that Crimsworth adopted a lifestyle of self-control in order to escape from the depression that clouded him, and that with any kind of disruption of spontaneous emotion, his self-control begins to deteriorate, leading him back into the arms of his old mistress, the “sorceress” with her “illusive lamp” and “vaulted home of horrors” (253). One of Crimsworth’s faults is his “inability to understand . . . such a wide range of behavior” (Kearns 143), and when faced by this newfound emotion and temporary loss of self, he finds himself sinking back into the familiar spell of depression.

Lack of "Psychic Rebirth"

Crimsworth eventually overcomes this newest resurgence of hypochondria, but it does not seem to change him, which is unusual, because in Charlotte Brontë’s other novels, when a character goes through a spell of mental agony, there is always a “psychic rebirth” (Malone 185), a reawakening of passion or new determination to overcome the obstacles ahead. For William Crimsworth, there is nothing; his ordeal does not affect him in any way. There is “barely any psychic change [in Crimsworth]; for the remainder of the novel, he is as aloof, as self-absorbed, as unperceptive as ever” (Malone 186).

Any reasons for this oddity are not clear, but it is possible that Crimsworth reverts back to stoicism in an attempt to evade yet another encounter with his dark mistress, depression. This could very well be a defense mechanism (Starzyk 150), bit if this is the case, then it is not a very effective one, because although it might help shield him from some feelings of melancholy, Crimsworth is ultimately depriving himself from living a full life.

Hypochondria as a Seductress

The language that Brontë uses to describe the emotional state that Crimsworth finds himself in is an odd mixture of compelling and disturbing diction and imagery, and she employs the use of “figures of speech that differ from those common in the novels of the previous century” (Kearns 144). Crimsworth’s hypochondria is described as a seductress, sorceress, and even a lover, and through the eerie, metaphorical descriptions of Crimsworth’s experience with her, Charlotte Brontë is able to portray with accuracy the lure of hopelessness and the dark, twisted beauty of despair:

. . . she [hypochondria] lay with me, she ate with me, she walked out with me, showing me nooks in woods, hollows in hills, where we could sit together, and where she could drop her drear veil over me, and so hide the sky and sun, grass and green tree; taking me entirely to her death-cold bosom, and holding me with arms of bone. What tales she would tell me at such hours! What songs she would recite in my ears! How she would discourse to me of her own country – the grave – and again and again promise to conduct me there ere long; and, drawing me to the very brink of a black, sullen river, show me, on the other side, shores unequal with mound, monument, and tablet, standing up in a glimmer more hoary than moonlight. ‘Necropolis!’ she would whisper, pointing to the pale piles, and add, ‘It contains a mansion prepared for you.’ (The Professor 253)

Using the imagery of a beautiful, dark siren seducing her victim, Brontë shows her deep understanding of the power of depression and its effects on the human mind. She is able to simultaneously show the looming, ugly, and terrifying shadow of darkness that accompanies depression and the beautiful lure of death to the hooded eyes of the person caught in its clutches (Malone 185). Crimsworth’s apparent longing for this land of the dead can be seen not only as a descent into depression, but it can also be interpreted as a death wish. It is unclear whether Crimsworth is actually referring to an actual longing to die or is simply comparing depression to Necropolis, but either way, it is clear that what Crimsworth feels during his bouts of hypochondria is severe, dark, and dangerously alluring.

What do you think?

Is Crimsworth's description of depression as a dark mistress a valid one? Can you relate to this observation? Share your thoughts in the comments!

Sources

Brontë, Charlotte. The Professor. 1857. Ed. Heather Glen. London: Penguin Books, 2003.

Howells, Coral Ann. Love, Mystery, and Misery: Feeling in Gothic Fiction. London: The Althone Press: University of London, 1978.

Kearns, Michael S. Metaphors of Mind in Fiction and Psychology. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1987.

Malone, Catherine. “‘We Have Learnt to Love Her More than Her Books’: The Critical Reception of Brontë’s Professor.” The Review of English Studies. 47.187. Web. 15 April 2013.

Starzyk, Lawrence J. “Charlotte Brontë’s ‘The Professor’: The Appropriation of Images.” Journal of Narrative Theory. 33.2 (2005): 143-162. Web. 20 April 2013.

Vrettos, Athena. “Victorian Psychology.” A Companion to the Victorian Novel. Ed. Patrick Brantlinger and William B. Thesing. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, Ltd., 2002. 67-83.