- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- Literary Criticism & Theory

Much Ado at the Globe: A Fictional Historical Essay

My name is Andrew Brown and I am a pickpocket.

The year was 1613 and it was early summer. I had had a rather productive morning – I had been in and out of bars and skulking down the crowded streets of downtown London, lurking amongst the wealthy and “relieving” them of their monetary burdens (Cook 205). After all, if their purses became too heavy on their belts, they might attract the unwanted attention of those who would exploit them for their riches. I was just doing the privileged patrons a favor, really. Still, though, my work was not done and I knew that I had to collect more money if I was to be welcomed back into my small band of fellow cutpurses and ne’er-do-wells that night so I decided that it was about time to pay a visit to the theater.

I will be honest – I do not much care for drama. I have never been one to sit – or, heaven forbid, stand like those “groundlings” in the pit (Gurr 18) – through a play and actually pay attention. Why people – rich and poor alike – like to spend their money to watch pretend people live out their lives is beyond me, but if it attracts those with wealth, which it often does, then I cannot complain, for it makes my job that much easier (Gurr 20).

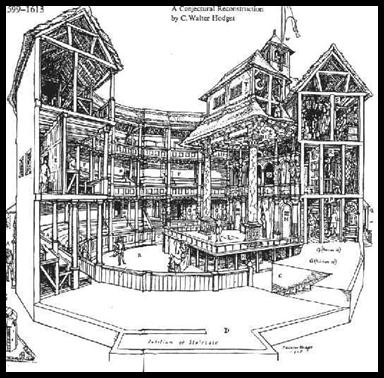

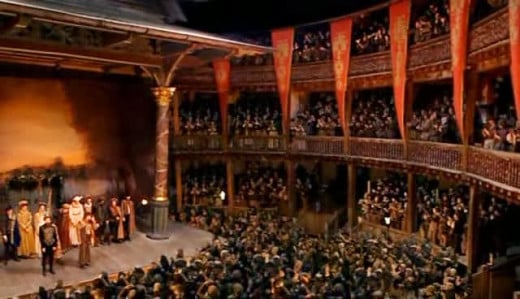

Despite my lack of interest in the theater arts, I found myself mildly curious at the amount of people pouring into the new Globe Theater that had been built just this year to replace the old one after its destruction (Neilson and Thorndike 117). Apparently this was a big deal – rarely had I seen a theater so packed. I knew this would probably be to my advantage, though, because it is common knowledge that “when the house was full, the crowding was intense.” (Gurr 18) The more people there were, the easier it would be to “accidentally” bump into someone and swipe their coin purse once inside.

It was not until after I was in the line to be admitted to the theater that I remembered why there was such a big fuss today. Fourteen plays were going to be “acted by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men at court as part of the festivities celebrating the betrothal and marriage of Princess Elizabeth” (Grice 565) over the course of this month, and this was, if I was remembering correctly, one of them. This particular play, as I soon found out, was written by William Shakespeare and entitled Much Ado about Nothing. I felt a bit disgruntled at this realization, for it meant that the play was probably going to be a sappy, melodramatic romance.

Despite my somewhat unscrupulous motives for going to the theater, I still found myself slightly in awe at the vast amount of seating and standing room. I had done this many times before and I knew what to do and where to go and even how much to pay to gain access to those with the most money. Despite how much I loathed handing over any of my spoils to another living soul, if I wanted to make any profit in the theater, I had to be willing to pay to get in. This would not be the first time that I paid admission “to get at the fat purses of the theatergoers.” (Cook 206)

There were two entrances to the theater. One led to the yard where the groundlings could stand in front of the stage and the other option was to go up a set of stairs to the galleries. It was obvious that the theater made a clear distinction between the “gallery sitters” and the “standers in the yard.” (Gurr 16). I knew exactly which route I wanted to take – even though I would have to pay more to get into the galleries – two pennies, instead of just one (Cook 181-82) – because that was where the wealthy sat. It was a small price to pay for the potential wealth I could accumulate by sitting in the galleries. And where there are rich people, there is more money to pilfer.

I did not pay much attention as everyone made their way to their seats. Instead, I leaned against the doorframe to the galleries and just watched. My eyes surreptitiously scanned the room, seeking out the biggest change purses and the fullest pockets (Cook 206). After years of practice, I was quite adept at picking out the best victims. Even as the crowd began to settle and quiet down in anticipation of the play starting, I still stood, watching them. I needed to find the best targets beforehand so I wasn’t bumbling around trying to pick the pockets of those that had just managed to scrape together two pennies to get into the galleries.

The people in the gallery, as I had noticed multiple times before on some of my previous exploits, definitely thought themselves above those in the pit. It was easy to notice this snobbish behavior from the way they continuously insisted that they “deserved better treatment” than those that were paying less to see the play (Gurr 18). I personally do not understand their insistence that they are “better” because they are wealthier, especially with the way they try to distinguish themselves from the groundlings through dress and presentation of themselves. Their “clothing was absurd.” (Neilson and Thorndike 9) Both men and women wore garments covered in an array of ruffles, bright and unseemly colors, a ridiculous display of jewels, and breeches. It is my earnest belief that they looked more like the “fools” this Shakespeare fellow was known for incorporating into many of his plays – comedies and tragedies alike (Mangan 50) than the noble and wealthy people they claimed to be.

And please do not get me started on the smell of the galleries and those who occupied them. For people who boast openly about their riches and wear gaudy jewels upon their clothing to showcase their wealth, one would think that they would take the time to properly bathe now and again. I know that I, for one, had I been born into a prosperous family and not the sixth child of a poor, sick, all-but-homeless peasant family in a small, decrepit house in Stratford (coincidentally, the same area where our playwright for today’s comedy, William Shakespeare, was born), would be taking advantage of the luxury of a bathtub (Wood 15).

Nevertheless, perhaps these privileged theatergoers thought that they were too good to bathe, because “cleanliness did not thrive” and “perfumes took the place of baths.” (Neilson and Thorndike 9) Who am I, a humble thief just trying to make a living by taking from the rich, to judge these upper class figures of society? They are rich, I suppose, so they can do whatever they want. Personally, I would recommend bathing, because the stench of sweat combined with that of strong perfume only serves to make the nostrils twitch more from discomfort. It would certainly make my job easier if they did not stink to high heaven.

The gallery in which I stood waiting for the play to begin so that I could start picking pockets and cutting purses was populated by men and women alike. Most of the women were accompanied by a man, for it was common for people to view a woman going to the theater alone as a prostitute (Cook 158). Some of the wealthier noblewomen, on the other hand, could be found seeing the plays “unescorted except by their pages.” (Gurr 20)

Finally, it was time for the play to begin. I was used to the way theaters worked by now and the setup of the stage. Believe me, I have been to more than enough performances in my career as a crook. There was no front curtain and the stage was essentially “bare,” with very little “scenery or furniture,” which the audience did not seem to mind in the slightest. Instead, the scarcity of scenery and props seemed to only strengthen the bond between the playgoers and the players on the stage as the audience was forced to immerse themselves into the drama in order to see in their minds what was supposed to be there (Neilson and Thorndike 130). That is what I have heard, at any rate. My girlfriend, Elisabet, who also happens to be a very cunning cutpurse, actually enjoys working the theaters when there is a play – particularly a romance – going on. Needless to say, she spends nearly as much time watching as she does picking pockets, resulting in her lovely fiancé doing all the work. That is the main reason I insisted on going to the theater alone today, her constant prattle about how “romantic” or “exciting” the performance is. It gets old after a while, trust me.

Any scenery that they did have were not elaborate, but merely indicators of what was supposed to be there. For example, as the play begun and the characters were welcomed into Beatrice and Hero’s home, there was no canvas painted like a house as a backdrop. Instead, there were two windows and a door that were placed near the rear of the stage, indicating where the house was and giving a rough example of the size (Graves 59).

As the play began, I found myself dreading having to listen and watch it as I did my work. I could not simply lurk around the gallery, snatching money from people – I had to blend in, to pretend that I was indeed watching and enjoying the show. The play began with a prince named Don Pedro and his possy arriving to the home of Leonato, the Governor of Messina. I instantly disliked the character of Claudio, who was a young man who apparently fought well in the war. On the contrary, despite my dislike for drama, I found myself drawn to the character of Don John, the prince’s bastard brother (Campbell 563). True, Don John was technically the villain and Claudio is supposedly one of the heroes of the play (Mangan 180), but I found Claudio with all his talk of love at first sight (complete rubbish, if you ask me), to be a bit of a stupid, frivolous man. This is reinforced later in the play when he automatically accuses his “true love” of being an adulteress without any sustainable proof near the end of the play.

I was just about to start my slinking about and liberating gold from the wealthy, stinky patrons of the Globe theater when the characters of Beatrice and Benedick were introduced. I sat down tentatively on the edge of my seat, not willing to give into the sudden urge to watch just a little more of the play, but strangely drawn in by the banter between the two characters as well. Much to my surprise, I found myself laughing out loud as Beatrice, Leonato, and the messenger discussed Benedick. I actually stored away some of the insults thrown around in the hopes that I might be able to use them against someone someday. I had to hold my sides, almost forgetting to hold my breath in a meager attempt to escape the smell in the process, when Beatrice commented about Benedick, “He is no less than a stuffed man. But for the stuffing – well, we are all mortal.” (Much Ado about Nothing I.i).

Sources

Campbell, Oscar James. “Much Ado about Nothing: Plot Synopsis.” The Reader’s Encyclopedia of Shakespeare. Ed. Oscar James Campbell and Edward G. Quinn. New York: Thomas Y Crowell Company, 1966.

Charney, Maurice, ed. Shakespearean Comedy. New York: New York Literary Forum, 1980.

Cook, Ann Jennalie. The Privelaged Playgoers of Shakespeare’s London, 1576-1642. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Graves, Thornton Shirley. The Court and London Theatres During the Reign of Elizabeth. New York: Russell & Russell, 1913.

Grice, Maurice. “Much Ado about Nothing: Stage History.” The Reader’s Encyclopedia of Shakespeare. Ed. Oscar James Campbell and Edward G. Quinn. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1966.

Gurr, Andrew. Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Mangan, Michael. A Preface to Shakespeare’s Comedies 1594-1603. Longman: Longman Group Limited, 1996.

Neilson, William Allan and Ashley Horace Thorndike. The Facts about Shakespeare. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1939.

Ornstein, Robert. Shakespeare’s Comedies From Farce to Romantic Mystery. London and Toronto: Associated University Presses, 1986.

Shakespeare, William. Much Ado about Nothing. In The Necessary Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. Chicago: The University of Chicago, 2009.

Wood, Michael. Shakespeare. New York: Basic Books, 2003.

As the play wore on, with balls and witty repartees, cunning plots, and disguises, I began to unconsciously relax more into my seat. My eyes were drawn to the stage and suddenly I could understand Elisabet’s words about connecting with the players on a whole new level with the lack of scenery and props. I found myself immersed in the action, on the edge of my seat. When Beatrice overheard a false conversation about how Benedick felt about her and immediately began to believe that she, too, was in love with the man, I felt a bit giddy myself (Much Ado about Nothing III.i). After all, it was more than obvious that Benedick and Beatrice were meant for each other, despite the fact that they were always at each other’s throats, even if they were not exactly aware until their friends used trickery to point it out to them. I also realized about halfway through the play that I was more than relieved that Beatrice and Benedick were a large part of the play (Ornstein 120).

I found nothing about Hero and Claudio’s relationship appealing in the slightest. Their relationship was a bland one, filled with the sappy melodramatic love at first sight garbage that I detest so much in plays of the time. Claudio, I felt strongly, was a coward for being too afraid to approach the woman that he supposedly was madly in love with (Much Ado about Nothing II.i). A man that has to have his friend flirt with a woman for him, in my opinion, does not deserve the girl in the first place. He should have gotten over his stage fright and asked her to dance himself.

Later on, after Don John’s devious plot to make Claudio think that Hero had been unfaithful to him, he decided that she was guilty without proof. For a man that claimed to love this woman so much, he did not give her a chance to defend herself. I will admit, I am a bit of a scoundrel myself, but I would like to believe that if Elisabet were ever accused of adultery that I would at least hear her out. I did not feel very sorry for Hero, though, either, because she did not try to stand up for herself and when Claudio found out the truth, she did not demand an apology but fell into his arms with mushy melodrama galore (Ornstein 123).

Benedick and Beatrice, on the other hand, were the greatest couple in the play. Their witty banter dominated the humor and they still managed to keep their funny, jesting relationship even after falling in love. I realize that some might have been taken aback by the use of trickery to make two people realize their feelings for each other, but I, for one, thought it was the perfect way to get the two sarcastic lovers together. After all, I am not one to judge – I first convinced Elisabet to give me a chance by telling her I was a noble in disguise. She thought that she could steal something from me although the only thing she ended up taking as her own was my heart. Do not get me wrong, though – I am still not a lover of romance. I will admit, however, that the drama and love in the play left me with a clearer view of how lucky I was to have a woman who did not behave like a bland, spineless child. I will be truthful here: I would not have been too bothered if Hero had died from shock when Claudio refused her at the altar; it would have made this particular subplot much more bearable. Sadly, there seemed to be an unspoken rule in Shakespeare’s dramas that said that no good characters could die and there had to be a happy ending in comedies (Ornstein 20).

I could hardly believe it when the play was over. It was astounding how gleeful I felt inside at the happy ending. I was also a bit baffled as I trickled out of the gallery and down the steps to the exit of the theater. I had gone into the Globe dreading having to bear witness to a drama but in the process I had realized that theater was not nearly as terrible as I had made it out to be. At any rate, this particular drama was not a complete waste of money. I would not say that I emerged from the theater a changed man, although it is true that I now have a greater appreciation for the arts and the people who go to view plays for entertainment. I actually had – dare I say it? – fun watching Shakespeare’s comedy Much Ado about Nothing.

Of course, it was only after I was halfway back to the meeting house of our band of thieves that I remembered – I had been so wrapped up in the play that I had forgotten to steal a single thing. I mustered up my courage (because I am not a wuss like Claudio or Hero) and went to face Elisabet and the others. I would come back with very little money and I would tell them the truth about what happened – that I was unable to pick any pockets because the audience was keeping an extra-sharp eye out for thieves.

I didn’t say that it was going to be the whole truth, after all.