Post-War Poetry of Witness: Making Sense of an Altered Reality

The first half of the twentieth century was marked by war on a global scale, mass genocide, bloody civil wars, revolutions, and repressions. In an atmosphere so volatile, it comes as no surprise that events of the world impacted its poetry.

From Eugenio Montale’s Italy in the aftermath of World War Two, captured in "Personae Seperata," to the Spanish Civil War and Rafael Alberti’s “Punishments,” to the Austrian poet Ingeborg Bachmann’s “Early Noon,” a forever altered Europe is depicted in the poetry of the age. These poems were directly influenced by the wars, and reflected what was occurring in the both the imagery and poetic structures. As the fabric of society and nations appeared to break down around the poet, so too did the poetry reflect this sense of deconstruction.

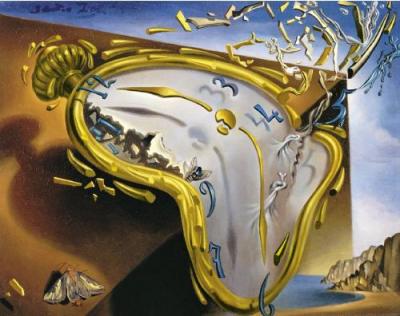

The Post-War poetry of Europe during the early half of the 20th centry is a poetry of fragmented time and space, of dreams, of the arbitrariness of fate. It speaks of the effects of trauma and grief, of the difficulty in remembering and forgetting. It is a poetry of ruin, a poetry with a sharp divide between past and future, a poetry with an overwhelming appeal to be believed, to be heard. Above all, it is an articulation of the compulsion to bear witness to an increasingly chaotic and incomprehensible world, a poetry of witness.

Poetry of witness is often a form that provides more questions than answers. It is in the act of questioning that the poets seek to make sense of their changing world. The reader comes to the growing realization that even more than being changed, the world has been irrevocably altered.

For Bachmann, Alberti, and Montale, previous modes of existence lay in ruins, and their poems reflect this sense of deconstruction. Just as the families, communities, and countries of the poets were rendered unrecognizable, so too did the poetry become unmoored in time, space, and construct. Loss of the familiar within everyday life led to a loss of relevance for the traditional forms of poetry, creating a new poetry of witness to articulate it all, and redefine the role of the poet within the world.

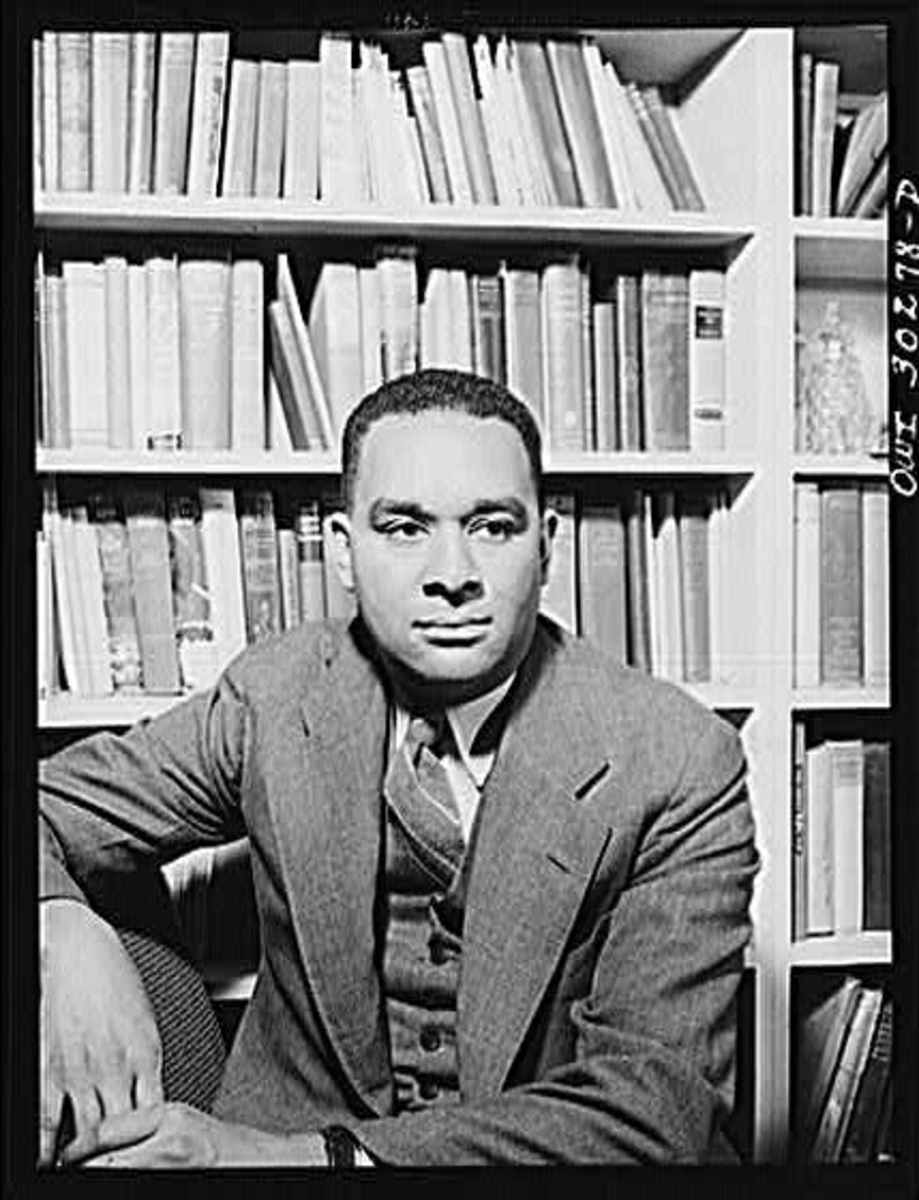

Rather than existing separately, as a figment of the literary imagination rather than the world, the poetry of witness is as firmly rooted within the real as it is within the workings of the mind. It is an overwhelming necessity to portray the workings of the world, in all its trauma, it’s flux of disintegration and change, a heightened responsibility of the poet to do this.

Poetry of witness may not provide the answer to how to sense can be made of it all, but in it’s attempt to illuminate overwhelming questions and uncertainties, brief glimpses of insight flicker forth like the golden scales of justice, the flickering day-moon, like Alberti’s “thunderbolt that shuffles tongues and jumbles words.” It is in this fleeting moment that comprehension begins to dawn, at times acceptance, and if one is lucky, redemption and hope.