Power at Sea:The Breaking Storm, 1919 - 1945 Review - Better, but Still Flawed

Lisle Rose's trilogy of books on naval power since 1890 starts out in an extremely rocky way with the decidedly flawed and mediocre volume of The Age of Navalism, 1890-1918. For many readers, this would probably be enough to put them off reading the series, but fortunately things do progress to the level of average and bearable - if not necessarily very good - in the second volume in the series, The Breaking Storm, 1919-1945. This book, which covers the interwar naval treaties and then combat operations during the Second World War, still has many of the errors of the first book - overly grandiose hypothetical situations, leaving untouched the actions of many crucial combatants, the sheer size and scope of the situation which the author wishes to cover, and a vaunting of the American navy which is often not backed up and can read as chauvinistic - but it overall cuts a much better figure than the first volume in the series, enough to make it it into a decent, if unspectacular, naval history of the period.

The book's beginnings include its preface, followed by maps - somewhat better than the first book in the series in giving at least some convoy routes, but still generally mediocre. After this the first chapter is about the Washington Naval Conferences and the efforts to rein in naval sizes as a budding post-war naval arms race threatened to spark off another war - this effort however, was troubled by major disputes and differing priorities between the powers, Its ultimate signature required significant concessions to be made by all involved.

A period of relative quiescence is covered by the book in the 1920s, with the major construction of new cruiser fleets by the Japanese, Americans,and British, and the German navy recovering from its nadir with the construction of new heavily armed pocket battleships. The real turning point however came with the 1930 London Naval Treaty which the Japanese hardline naval factions took very negatively, leading in part to increasing Japanese estrangement from global arms limitations and political radicalization.

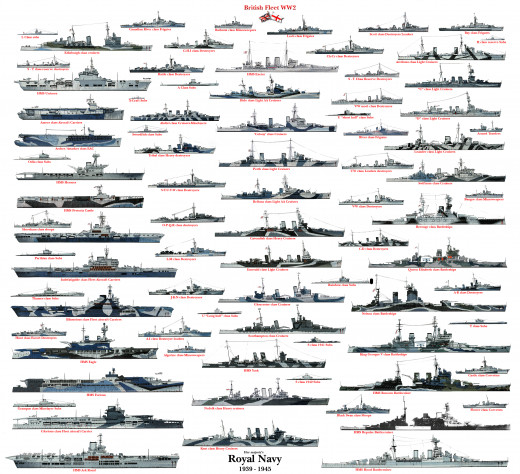

After this, The Breaking Storm takes a look at each of the big navies in turn, starting with the Royal Navy, castigated for its decline despite its still formidable size, as its ships aged and enemies strengthened relative to it. Even more important was declining morale and deep personnel problems. British diplomacy effectively encouraged the Germans to start to rebuild their fleet, and in the long term it would be used against the British, while they backed down in front of Italian aggression in Ethiopia. The British lacked the funds to engage in a new naval arms race on equal terms with the Japanese, Italians, and Germans, and although they made important steps with carrier aviation - albeit limited by long inter-service battles and small aircraft complements - the British went to war with a fleet that was the largest in the world but also dangerously over-extended and stretched.

Germany takes the next position, with the revival of German naval power under its naval leader Erich Rader, Major new battlecruiser fleet elements, cruisers, and destroyers were built, and intelligence improved, but limited resources and greater interest in land and air operations throttled the German fleet's growth.Furthermore it was riven in its own controversy between surface units and submarines - never fully incompatible between the two, but neither arm was strong enough when war broke out, despite the best effort of Donitz, head of the German submarine program. This chapter also contains a short section on the Italian fleet, but it is mostly critical in nature, attacking its perceived lack of fighting spirit and training.

Following this is Japan, The Japanese built up a powerful fleet to try to match the American navy, laying down the massive Yamato class battleships to provide for the most powerful battleships in the world. A highly capable naval air arm with superbly trained pilots - although there were never enough of them - and unprecedented naval airpower concentration doctrines, joined greatly enhanced amphibious warfare capabilities with sophisticated doctrine and plentiful experience. But it never had enough trained officers and took too long to train new ones, was always overly ambitious and over-reached to disastrous effect.

The middle of the book carries quite a few photos.

Last but not least come the Americans, who prepared to fight a war with strategic mobility unparalleled by any other nation as their plans called for an offensive across the Pacific to the heart of the Japanese empire. This also led them to develop amphibious landing doctrines, like the Japanese, and to build up the nucleus of an ultimately decisive carrier fleet based on fast and flexible operations that would prove much more mobile and useful than the battleships.

After this there is a chapter which lays out a general overview of the Second World War at sea., focusing on the tonnage war in the Atlantic and the Pacific carrier battles, and emphasizing the massive and industrial nature of the war.

In the most hypothetical chapter in the book, there is a section about the potential missed chances of the Axis powers as seen by the author - invading Britain in Operation Sealion, the Japanese attacking the Panama Canal, the Japanese and Germans rendezvousing in the Middle East after a Japanese naval offensive into the Indian Ocean, and the Japanese defeating the Americans at Guadalcanal.

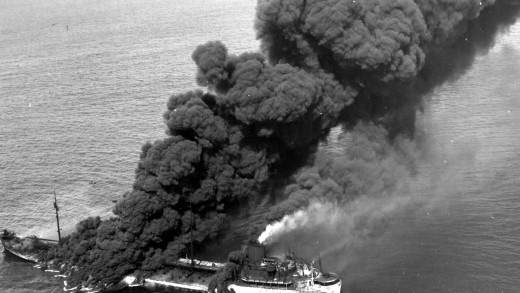

The tonnage war in the Atlantic takes center stage, relating the combined German air, surface ship, and submarine offensive which attempted to strangle the United Kingdom by destroying its communication lines and merchant marine. It covers the build up of the German U-Boat arm and then the strategies adopted by the German navy in its communication and tactics to defeat the British. Much focus is paid to relating anecdotes and the living conditions and mentalities of British and German sailors, all of whom were in horrifying and terrible, dangerous and frightening conditions. Both sides were in a constant race to develop new technology - radar, snorkels, escort carriers, throwing anti-submarine warfare weapons, magnetic anomaly detectors, radio trackers, improved sonar, acoustic torpedoes, torpedo decoys, etc. - and penetrate the other's communications: ultimately the Allies won this race, made most clear by Ultra, the breaking of German communication codes upon which the entire tightly coordinated German U-Boat campaign depended. Worst of all was when the Americans were brought into the war, and despite initial terrible losses in poorly coordinated anti-submarine warfare of their own, they brought industrial capacity and shipbuilding which utterly dwarfed the British one. This meant the Allies won the battle in the end, and were able to proceed to the invasion of Continental Europe, as related in the D-Day and logistics section at the end.

American sailors and their life and type is the following subject, painting a picture of disciplined and innovative men. It is less complimentary towards the American obsession with a battle line fleet battle, like Jutland of twenty years before, although it compliments the Americans on their intended way of doing so, with decentralization and initiative. Much ink is devoted to discrediting conspiracy theories about Pearl Harbor having been set up to bring the Americans into the war, and emphasizing its morale effect on the Americans. After another section of odes to Americans and their spirit during the war, it goes back to the Old World with the Mediterranean conflict, writing a laudatory account of the British and their carrier operations against the Italians and their stuggles to supply and make useful Malta.

A final chapter is about the American war in the Pacific, starting with the American submarine war which proved devastating to Japanese communications and commerce, The continuation is about the American drive across the Pacific with their powerful carrier fleets, both the Central and Southern Pacific offensives, focusing on the Battle of Leyte Gulf and the Marianas Turkey Shoot against the Japanese - although it is harshly critical of the decision to attack to liberate the Philippines in the first place as having extended the war. Its final component is about the prospective invasion of Japan and a defense of the decision to use the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and a eulogy for the British who had been supplanted as the greatest seapower on Earth by the Americans.

The Second World War was a conflict of such scale and size that it makes it quite difficult to give any reasonable overview of it in a regular book. Rose's entire series could have been just about the Second World War and it still would have left the conflict only covered moderately, with plenty of extra room for detail. 400 pages - not even to mention the cover of the Interwar period, and the preparation of the navies for the conflict, neither of which are short - does not suffice.

Within these limits however, Rose does a reasonable job. He does have an eye for providing for a stirring and romantic description of some of the theaters of the war, such as the Atlantic - where in addition to giving a good overview of events from a technical front, he also includes moving and dramatic snapshots of the lives and struggles of men and ships in the deadly storm-tossed grey waters of the ocean between Britain and America, churned by convoys between Britain and America and the desperate efforts by the Germans to sink enough ships to put the British out of the war, and the equally desperate efforts by the Allies to defend their merchant ships.

Rose should also be credited for greater attention paid to doctrine and training in this book, which was rather lacking in his first book, but is expanded upon to include subjects such as amphibious landings or carrier operations. Things such as the training of Japanese pilots - admittedly a rather heavily covered topic in any naval history of the Second World War - receive their due place. It goes deeper than the normal declaration of them being the best pilots with discussing how the extensive training lead to curiously fragile pilots, convinced of their superiority and too eager to show their skill in battle, taking unnecessary risks and cracking under the pressure of war.

But some of Rose's failings from the first book continue to exist. There is nothing wrong with hypothetical speculation about what might have been done, but his chapter in the middle of the book on hypothetical German and Japanese (as usual the Italians are ignored....) options to defeat the Allies has even more than his proposals of possible German routes to victory in the First World War, an era of unreal over-optimism and amateurish ignorance of the problems afflicting his proposals. Sealion, the German invasion of Britain, is advocated for, despite the horrific - nigh impossible - odds confronting the Germans, with the argument that it might have worked since British morale could crack, His proposals about the Japanese attacking the Panama Canal at the beginning of the Pacific War are even more ludicrous, in light of the severely lacking Japanese fleet train which was operating at the limits of its endurance just to bring the Japanese fleet to within striking range of Pearl Harbor, much less thousands of kilometers to the east.Similar proposals of Japanese full forays into the Western Indian Ocean appear horrifyingly unrealistic in light of poor Japanese logistics, lengthy logistics lines which would be vulnerable to British counter-attacks, the inability of the Japanese to sustain themselves for long in the Western Indian Ocean, and that the author's proposal - a mass uprising in India - seems terribly unlikely. It shows that the author has a continuing tendency to think too highly of naval ships in of themselves as being the arbiters of conflict, rather than as parts of an overall strategy - such as his proposal for pinprick attacks by the American fleet on Japan after Midway, despite their limited impact, instead of capturing territory to enable a truly effective war to be waged against Japan with island bases, and the Japanese merchant marine unable to reach Southeast Asia with its resources. Certainly, his proposals about the Southern Pacific offensive have merit as perhaps being unnecessary, but his alternatives show themselves as useless.

There is also the selectivity of Rose's choices and chauvinism at times: the naval campaigns of the Baltic and Black Sea between the Axis and the Soviet navies and air fleets are simply not mentioned, and his portrayal of the Italians - with a fleet far larger than the Germans and of often forgotten strategic importance given how it kept the Mediterranean closed to British shipping and mostly succeeded in supplying Axis armies in North Africa for 3 years - is laughably short and stereotypical, relying on characterizations of lazy Italians and lack of professionalism. It indulges in innaccuracies too, such as claiming the Italians lost every battle, decidedly not true as shown by Operation Harpoon, and in any case most of the battles between the British and the Italians were draws, or that the Italian cruisers were tin-clads without armor - true of the early Italian cruisers, definitely not true of the Zara class cruisers. Italian defeats like Matapan were the exception, rather than the rule. Insultingly, it mentions the Italian navy as only a small portion of the German chapter, makes no real attempt to explain its wartime strategy - instead relying, as always, on explanations of it being cowardly and lacking the morale to sortie against the British - and its section on the Mediterranean conflict is short and written from above all else the British and German point of view. The French meanwhile, make almost no appearance in the annals of naval power, despite their formidable post-war fleet - just a dismissive small reference about its neutralization at Mers-el-Kebir.

There are too many omissions, flaws, and over-reaches for this book to rank as being an excellent naval history. But Rose does make enough improvements from the first book in the series to make The Breaking Storm, 1919-1945 into a reasonable book. It gives a decent overview of most of the big naval operations of the war - although its Mediterranean coverage is lacking - and of the mentalities and problems facing the naval powers, and the lives of their sailors and men. It is reasonably easy to read and well written. It must be read in conjunction with other books for a more detailed and analytical look at naval operations during the war, but it is a readable and interesting tome for a neophyte looking to have a graspable overview of naval operations during the conflict and preparations leading up to it, even if it must be taken with a grain of salt.

© 2020 Ryan C Thomas