Quality Articles Fall Victim to Google Panda and Anti-Duplication Hysteria

Have you been a Panda victim lately?

Writers, and the public in general, increasingly have been encountering censorship, but who would have expected Google — and its Web-searching tools — to become a major driving force? However, it appears that Google — and in particular its Web content "filtering" process tagged as "Panda" — has emerged as a serious impediment to productive writing.

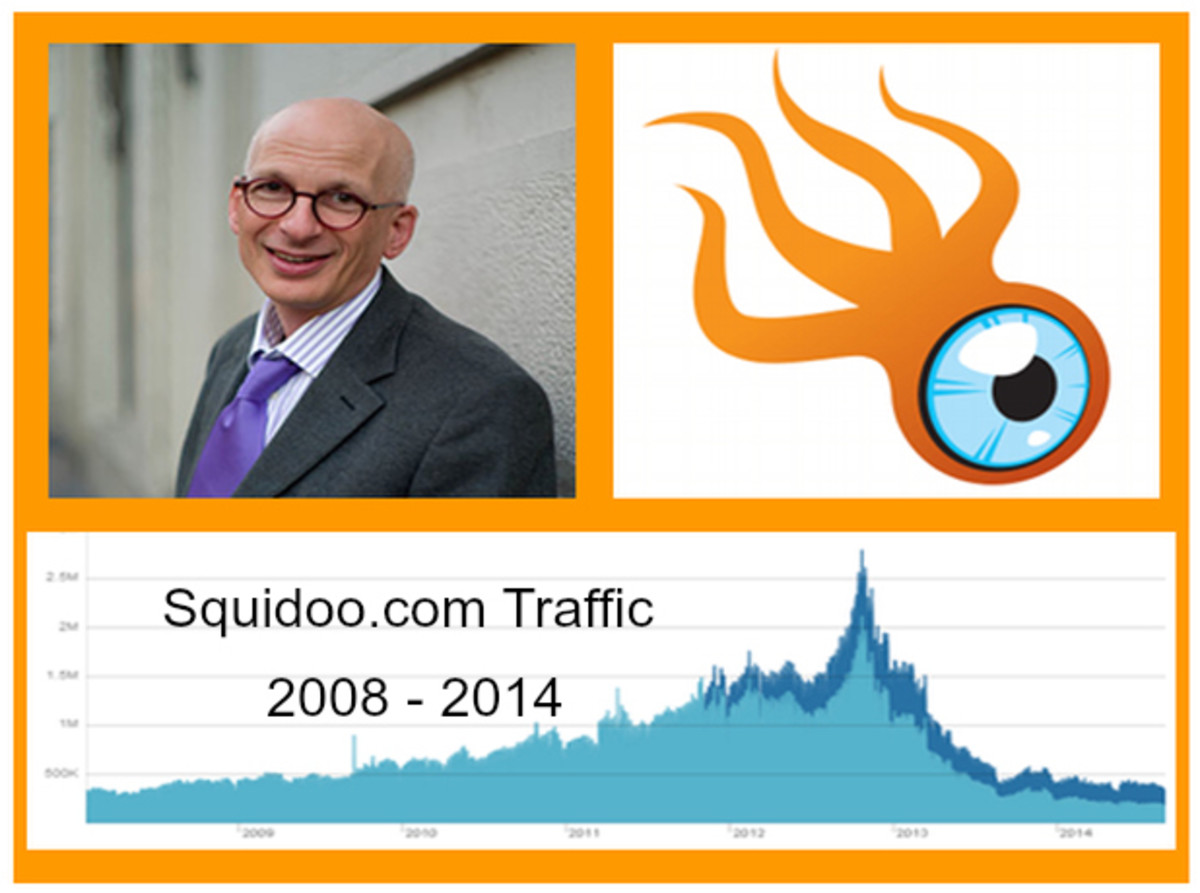

Panda — no, not the cute, lovable Chinese bear, but basically, Google's name for a kind of content-screening algorithm — was instituted by Google in about 2011) to try to address a real problem: rampant, deliberate, reckless, and unbridled duplication of content by a number of content providers (in quest of spreading a wide net to be found in Google searches and thus to catch Webpage ad revenue). Panda reduces the number of SERPs — Search Engine Results found in Google search queries. In response, so as not to be screened out in Web searches, various major online publishers and content providers have adopted similar "house rules" — in-house screening procedures to try to conform to this stringent new paradigm by imposing severe strictures against any duplicative content and insisting on entirely pristine, virgin content.

Lots of people, including many writers, have been applauding Google's move because it supposedly thwarts plagiarism. This kind of content piracy (stealing someone else's written work and portraying it as your own) has certainly been a problem ... but Google's robotic crusade against virtually any duplicative content is also creating an unforeseen, and perhaps ultimately more harmful, problem

Penalized for Adapting Your Own Work

What's the problem? Traditionally, many, possibly most, writers have reprocessed their own content, updating it, expanding it, tweaking it, inserting it into new articles. If you've expressed a concept well, why should you have to junk that wording entirely and somehow find entirely new and different words to try to express the same thing? Yet the emerging new paradigm seems to admonish any such re-use of past formulations and phrases, and to convey a mandate that all content emerge ever new from the writer's brain.

Many writers create new material (such as articles on important topics) by adapting and expanding their own older material, perhaps from relatively small sections of other much longer articles. Often this means that some of the new material will be duplicated (key phrases, especially those describing very specific objects, procedures, or concepts) — even though the overall wording may be changed substantially, with totally new case examples or other material, and new content added

However, more and more writers are finding that, because of the emerging Panda paradigm, their new articles may be rejected, or suspended, by the online publisher for a "duplicated content" violation. "Substantial similarity to another work" can mean not just duplicating the exact wording elsewhere on the Web, but may include "close paraphrasing, among other forms of misappropriation or copying of content...." In other words, you can't just change the wording of previous material, you can't even paraphrase it — which seems to mean you can't really use it again at all.

"Cure" Worse Than the "Disease"?

Unfortunately, the ultimate result of the Panda "remedy" may be worse than the disease if it stifles even useful and essential duplicative content. Possibly, Panda (and online publishing sites that seek to comply with this paradigm) may be relying on far too mechanistic and draconian an algorithm to assess duplication

What if you write a short article, with the intent to develop that later into a more extensive article on the same theme or topic? Watch out — the very words and phrases you use in your initial short article might trigger a "duplicated content" violation when you try to re-use some of the same expressions and phrases later.

So writers may find that plagiarism of their work has diminished (this is yet to be demonstrated). However, the price may be to frustrate or encumber their efforts to produce more new work in the future. It's hard to say exactly what the best solution to the problem of content piracy might be ... but when you leave it to the robots, you may get something far different from what you bargained for.

Originally published 2011/12/06

This content reflects the personal opinions of the author. It is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and should not be substituted for impartial fact or advice in legal, political, or personal matters.

© 2011 Lyndon Henry