- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Commercial & Creative Writing»

- Creative Writing

Randy Godwin and 1951 South Carolina - A True Short Story

Randy Godwin and 1951 South Carolina.

Have you read Randy’s great story?

It's superb, and it reminded me of a true story of my own experience in the Deep South, so long ago, although my story is…well, you’ll see.

Dad was a high steel ironworker, and it was a job that required lots of moving around, so I saw quite a bit of the U.S. in my early days. One such job was on the Savannah River’s South Carolina side, and was called, appropriately enough, “The Savannah River Project." It was later renamed "The Savannah River Nuclear Bomb Plant," and even later, “The Savannah River Site."

Dad bought two acres in the piney woods and pulled in what was then a huge house trailer for us to live in. We put in a well and a septic system, and the power company brought in electricity. For a nine-year-old boy it was Heaven, because I had a dog and the job of killing the hundreds of rattlesnakes that threatened my mom and sisters. I was the only boy and liked it that way because I got special considerations.

Our home location was just across the Savannah River from Randy’s story location, and my experience in the segregated South was similar in many ways. Every facet of life had a white and a colored separation, and for an Iowa boy, it was shocking to have full-grown, black adults step off the sidewalk to allow a little white twerp like me to pass. In fact, it was downright embarrassing, but a protest from either black or white was dangerous, because the Klan was everywhere, and like the Taliban of today, any misstep could earn angry retaliation. I once caught hell from a white stranger for drinking out of a 'colored' fountain.

One summer evening, my cousins, sisters, and I were playing outside while the adults were inside talking, because kids in those days were not allowed to bother the adults, nor did we want to. We were playing hide-and-go-seek when we heard a strange, wailing cry from down in the swamp.

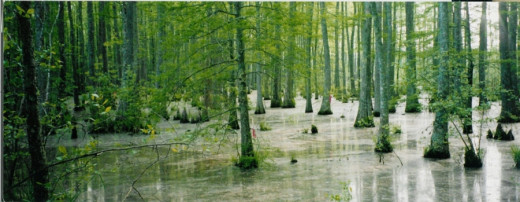

Our acreage was on high ground, but just a half a mile away and down a long hill was a big swamp with alligators, snakes, and quicksand. It was fed by a slow stream of milky green water, and was divided by the new blacktop road where we met the school bus. Dad and I had gone down there once, but the leeches, mosquitoes, and rotting stench drove us back after venturing in just a few hundred feet.

The hide-and-seek game stopped, and we all came out of hiding, staring in dread through the blackness at the invisible swamp we all knew was there. Then it came again, a thin, quavering and terrifying call that sounded like someone in desperate peril calling for help with his last bit of strength. We all ran for the trailer to get the adults.

For a long time there was silence, and my mother, father, Uncle Dick, and Aunt Jean were looking at us kids with accusing eyes when the same bone-chilling cry came from down in the swamp. My mother and aunt simultaneously put their hands over their mouths in female horror, and my mother gasped, “It’s the damned Klan, and they have some poor negro down there!”

That startled all of us kids, because we had never before heard my mother swear. Then my dad said, “To hell with the damn Klan! I’m going down there!”

Wow! Two revelations in one night, because we had also never heard him swear either, although I had my suspicions after often hearing him mutter incoherently while working on our car. I, and my cousin Frank were both fluent in expletives, of course, but we were careful never to reveal our expertise.

My dad and Uncle Dick armed themselves with double barreled shotguns, while my mother and Aunt Jean piled blankets in the trunk, which seemed odd in one hundred degree heat and one hundred percent humidity, but I knew better than to question their wisdom.

To our utter astonishment, the shoulders of the blacktop road were covered with cars because the plaintive cry had been heard by lots of anxious people. Armed men, women with blankets, and fortunate little boys who were allowed to ride along, cluttered the roadside. Girls of course, were not permitted, lest they see something that would forever ruin their delicate sensitivities. Most of the men were Dad's fellow iron workers who also lived in the area. They were a clannish bunch, and most were from the upper Midwest, where there was no segregation. They all knew it was the damned Klan.

As Dad and Uncle Dick switched on flashlights and prepared to enter the horrors of the nighttime swamp, there was a big commotion on the side of the road and we all rushed to look. A pair of muddy ironworkers were supporting an equally muddy old black man, as they climbed up the shoulder. Dad and Uncle Dick rushed down to help them, and they all gathered in a circle around the stricken man. The old man was known to all of us as a local farmer who sold delicious watermelons out of his ancient truck. We had no idea what he had done to get himself into such trouble, but he was well liked by all. The anger was growing.

We went back to the car with the womenfolk and waited for a long time. Then the cars started slowly leaving one by one, but we were still there. At last, Dad and Uncle Dick got in the front seat and just sat there in silence. Then one of them snorted and they both broke down in helpless fits of laughter. When mom asked what was so funny, they looked at each other and cracked up again, slapping each other on the shoulder and gasping for breath. At last, they subsided and Dad spoke.

“He wasn’t in any trouble at all. It turns out that he was just dead drunk and decided to spend the night down there because he was too drunk to walk.”

Mom spoke up. “So why was he was calling for help?”

Dad and Uncle Dick started laughing again. “It turns out that he wasn’t calling for help at all. He was just calling for his old coon hound!”

...

When the old man sobered up, he was mortified at all the trouble he's caused, and he was also a little scared that there might be some Klan retaliation, but the iron workers had a great story to tell, so they assured him that all was well. Then they found out that he made great barbecue, and he started doing a brisk business out of his truck. I wish I could remember his name, but it's lost to history. His grandson and I played together some. That was permitted.

That was all a long time ago, and Mom and Dad have passed on, but the memory is fresh in my mind. I still own those two acres, but the swamp has been drained and, like the KKK, it's no longer dangerous.