- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Books & Novels»

- Fiction»

- Science Fiction & Fantasy Books

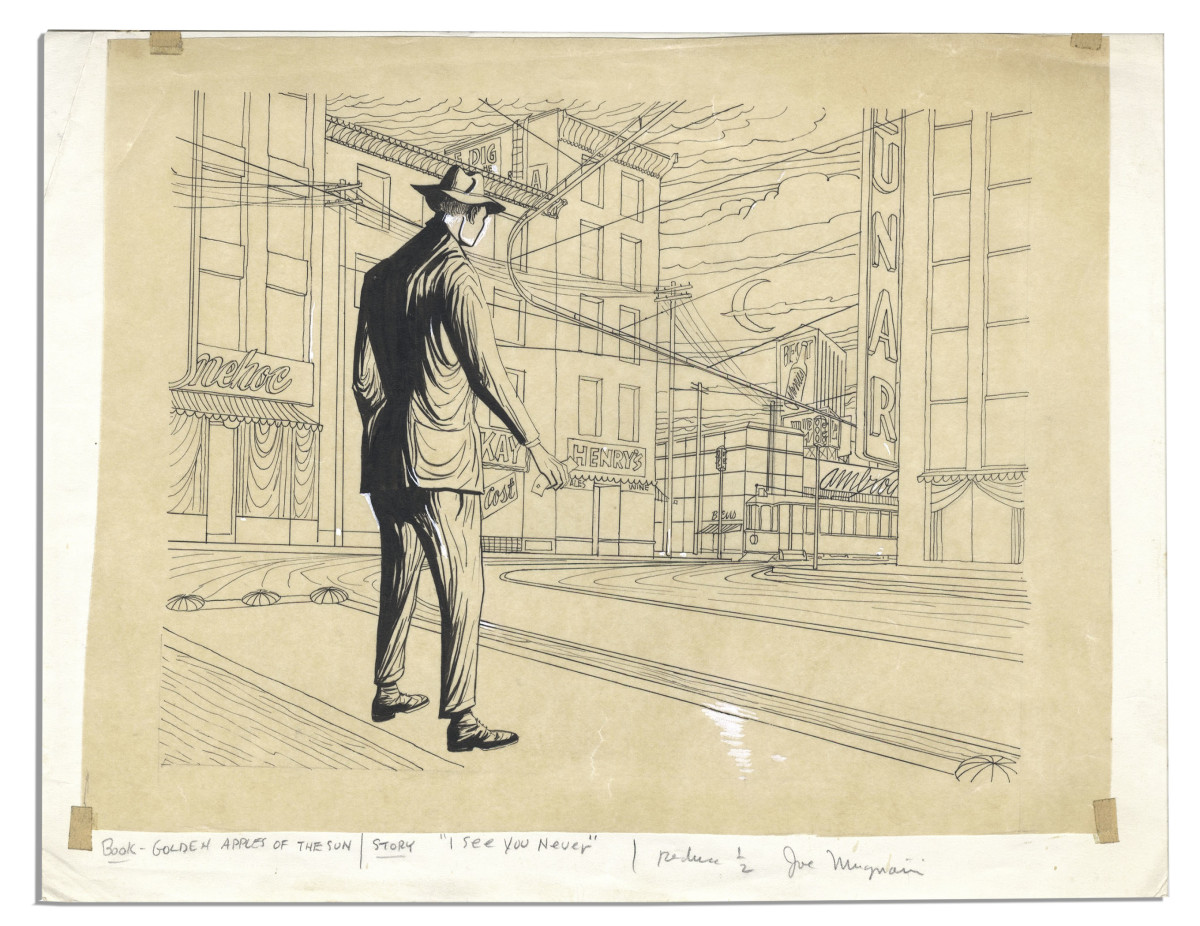

Ray Bradbury's The Illustrated Man: A Book Review

Today we're going to take a look at a short story collection of science fiction author, Ray Bradbury(1920-2012). The collection is The Illustrated Man; there are twenty stories.

What I'm going to do is compare and contrast him to Philip K. Dick. There is a point I want to make about Dick's work, that didn't occur to me until I started thinking about writing this review of Bradbury. Any of you who are both science fiction fans and thinking about giving Dick a try, you might find the following remarks useful.

Let's get started

Bradbury, as a science fiction author, comes out of the same stylistic mold as Philip K. Dick. What is that stylistic mold?

Well, like Dick, Bradbury's science fiction is not classifiable as hard science fiction. I have previously defined "hard" science fiction as: left-brain-oriented and technical, so much so that the science fiction apparatus (the futuristic science and technology imagined) is, itself, a kind of character in the story. In this sense, the "medium IS the message."

With Bradbury and Dick, the specific science-technology apparatus is usually used to launch the reader into the story; the futuristic encasing functions more like a means to the end of storytelling, rather than an integral part of the process. That make sense? Good.

I'll solidify this point when we look at some of Bradbury's stories from The Illustrated Man.

First of all...

This is just a minor point I want to start with. It may hardly seem worth mentioning, but all of the stories in The Illustrated Man were published in either the late 1940s or early 1950s. We are given that on the appendix in the back of the book.

I mention this because, as I said in my review of a short story collection of Philip K. Dick, both writers treat the future in material terms, in such a way that---as far as I can tell so far---seems to be characteristic of science fiction from that period in general, to a greater or lesser degree. Dick and Bradley treat futuristic technology with what I have already called a sensibility of a kind of World's Fair euphoria.

Basically, Dick, Bradley, and science fiction writers in general in the period of the late-1940s, 50s, and perhaps early 1960s, thought we would be living like The Jetsons today: talking, intelligent robots; flying cars; transport chutes; the virtual abolishment of manual labor; beds making themselves; dinner magically appearing on the table and the remains whisked away and cleaned by computerized and robotized appliances, and so forth.

Adaptability

Also, like the work of Philip K. Dick, Bradbury's work has proven readily adaptable to the stage, big and small screens. On the back dust jacket we learn that he had adapted sixty-five of his short stories for television, something called Ray Bradbury's Theater; in addition to winning the Emmy for his teleplay The Halloween Tree.

I think there is a reason that his work, like that of Dick, is so readily transferable to other mediums of storytelling. I believe it lies in the relationship of the imagined futuristic apparatus is used in relation to the story: the science-technology stuff is merely used as a launching point into the story, into the imagination; once you are launched into this space, the futuristic science-technology stuff recedes. This approach makes the work very accessible for right-brain-oriented people like myself. In other words, the concept is usually a right-brained one; the starting point is vaguely left-brain-related; soon dominion is given over to the right brain. That's how I see it in any event.

Mode of Conflict

There is just one, broad general difference between the work of Dick and Bradbury, that I can think of right now, but it is rather important. Though I, personally, love the work of both gentleman, let me make the following distinction, so that people unfamiliar with either of them will get a clearer picture of what they will be in for, should you decide to engage one or, hopefully, both of these authors.

The way I would broadly characterize this difference is this way: Bradbury's writing will appeal most to people who like impressionist painting; Dick's work will appeal most fans of surrealist art.

What am I talking about?

Well, by using two forms of painting as an example, I am making a characterization about the different degree to which "reality" is "warped," for lack of a better expression.

So, what does that mean?

Fiction is, by definition, "false" and "made up," as it were, according a deeply cynical view. Depending upon the genre of fiction, we are talking about different degrees to which the laws of physics are broken, if you will. Literary fiction does not break any laws of physics. Crime novels begin to stretch laws of plausibility---more or less depending on the author; mystery novels are the same. Fantasy novels completely shatter those laws, and indeed, ignores them.

Hard science fiction grounds itself in the known laws of physics and speculates upward (theoretical physics), but tries to stay true to that which is known.

The science fiction of Bradbury and Dick does not do this. Their work is not classifiable as hard science fiction. Remember that I said before that their writing exhibits a kind of World's Fair euphoria about the future in material terms; they imagined The Jetsons, in short. They, and writers of that mold, are not concerned with any rigorous grounding in strict scientific fact; something vaguely related to known science-technology is used as an instrument to point the reader's attention here or there.

Anyway, that is, in my opinion, the necessary starting point at which one must compare the work of Bradbury and Dick. Given that, then, as the starting point, I say that Dick will have the most appeal to people who like surrealistic painting; and Bradbury will most appeal to fans of the impressionist school.

Given that...

1. Dick's plots are far more elaborate in general,--- sometimes downright Rube Goldberg creations (see Time Out of Joint and Eye in the Sky for example)---than those of Bradbury. Indeed, what I want to say about Dick is that he was not afraid to stack up layer upon layer of impossibility.

2. Because Dick's plots are so elaborate, even wacky (which can get old in the wrong hands), they are always anchored by perfectly reasonable, down-to-earth, even somewhat heroic, "normal" protagonists. This feature is needed to safely pull everyone, including the reader, through the funhouse back to the other side, standing on solid ground again. Dick reminds me a lot of Dean Koontz in that regard. Koontz's novels seem to really need to be anchored by straight up, heroic, see-the-world-in-black-and-white, Captain America-types because his plots are so complex, with so many moving parts, and the villains tend to be evil to the extreme that they simply have to be leavened by the extreme from the forces of light. Does that make sense? I hope so. Stephen King, on the other hand---not so much.

3. The moral lessons Dick tends to offer, therefore, are rather standard, American centrist-liberal, Enlightenment, modernist---and there is nothing wrong with that.

4. With Bradbury, the plots are not so reality-shredding, the heroes can be more complex and ambivalent; its even okay if everybody dies at the end.

Let's take a look at one or two of the stories from The Illustrated Man.

Kaleidoscope

This is a truly sad story about a rocket that blew up while in space. The astronauts each hurtle to their deaths, in different directions, away from each other. They talk as long as they can maintain radio contact. They all dies of course, but one dies with the hope that---from his perspective---a wasted life can mean a tiny little, fleeting something as the onrushing Earth's atmosphere burns the light from it.

That's it. That is the story: poignant. This belongs in any fancy "literary" story collection in my opinion. Notice: the rocket ship is only a vehicle to transport the imagination. What is it like to die alone?

The Rocket

This is simply a story in which we, the readers, are asked to imagine what it is like to imagine other people imagining. What decision does a poor man make, who only has enough money to send one of his family on a rocket to see Mars? Will it be his wife, one of his three children, or himself?

I don't want to spoil things for you. Let me just say that the way that Fiorello Bordoni solves this Solomonic problem is both touching and sweet. Notice that the rocket trip could have been anything: a trip to Paris to see the Eiffel Tower, a trip on an ocean liner, a ticket to the World Series, etc. The way the father resolves the dilemma requires no great sci-fi fix. This story, too, would be well represented in any "literary" collection.

The Illustrated Man

I consider this a straight up horror story. In fact, there is nothing even vaguely science fictiony (I just invented the word 'science fictiony') about it. The tale is more like the magical realism of The Twilight Zone.

In fact, I think that is another difference between the writing of Dick and Bradbury. Bradbury uses more of what I would call magical realism than Dick.

What do I mean by 'magical realism'? Isn't it a contradiction of terms like jumbo shrimp?

Well, no---at least not the way I understand the term. To me magical realism is fiction of one kind or another (usually belonging to the province of what is called 'speculative fiction') that present the uncanny in such a way that suggests that such forces are a normal feature of the universe that we live in; an opening---whose cause is unknown---occurs so that we may witness and/or experience them. There is usually no identifiable, direct science fiction or fantasy catalyst which creates the uncanny phenomena. Follow?

Anyhow, I'm saying that Bradbury employs that technique more often than Dick does, from what I can tell so far, at least.

This story, "The Illustrated Man," is about a circus performer who gets injured. In order to keep a job, he gets himself tattooed from head-to-toe, front and back. Well, it turns out that the drawings hold predictive value... and your imagination can take it from there. But notice: no futuristic science and technology employed.

The Zero Hour

What is this story about? Think of Children of the Corn in a strictly science fiction context. Instead of a demon, the children summon invaders from Mars!

The Highway

This is a little story about the fear of the coming end of the world, taking place very quietly on the side of a highway. The interaction takes place between an old man and some kids, whose car needs water on a scorching hot day. That's it, but the effect is powerful.

Again, there is no discernible "science fiction" apparatus; and this story, yet again, deserves to be in any "literary" collection.

The Long Rain

This story simply asks the question: How long can you hold onto hope in the face of hopelessness?

The protagonists are on Venus where it rains all the time---literally all the time. The only thing that makes the place livable are man-made structures called Sun Domes. At these places there is shelter from the rain, warmth, companionship, hot coffee and delicious things to eat. Well, it comes to pass that some men have to trek across the surface of the planet, pounded by the rain until they get to one, which may not be as simple as you think.

Again, what makes the story strictly "science fiction" is the fact that humans inhabit Venus (and all that goes with such a circumstance), but the situation could have been anything. It could have been a tale of survival on a snowy mountain, a North African desert, or aboard a lifeboat in the middle of the ocean waiting for rescue. The situation is the same: How long can you hold onto hope?

The Other Foot

What we are asked to consider in this story is exactly what the title says. What happens when "the shoe's on the other foot"? Black and white race relations are taken on. What makes it science fiction is the fact that we're dealing with interplanetary travel and settlement. BUt, yet again, the story has a way of leaving that apparatus behind. I don't want to spoil anything for you, but remember what I said: All of these stories were published in the late-1940s or early-1950s.

This is a wonderful story of redemption and second chances.

Conclusion

I will leave it there. I hope my remarks, especially those comparing and contrasting Dick and Bradbury, will give you a reasonable picture of what we're looking at when it comes to the science fiction of Ray Bradbury. I hope the cross section of stories from this Bradbury collection, The Illustrated Man, that I lightly commented on here helps in solidifying that picture.

Thank you for reading.