Russia - Books I Have Known

introduction

With all the fuss concerning Russia now-a-days, I thought I would share some of the books I have read on the subject.

My list is by no means complete and no doubt excludes many fine volumes, but I can only speak to those that I have read myself.

Nevertheless, these works should provide anyone interested with a reasonable idea of Russian history and character.

Index

The following is an index of the books under review. They are in order of appearance and you will have to scroll down to view the review for any individual work.

The March of Muscovy by Harold Lamb

Ivan III and the Unification of Russia by Ian Grey

Ivan IV The Terrible by Henri Troyet

East of the Sun by Benson Bobrick

The Shaman's Coat by Anna Reid

The Gulag Archipelago I - II - III by Alexander I. Solzhenitsyn

Peter the Great by Robert Masse

Russia in the Era of Peter the Great by L. Jay Oliva

Catherine the Great by Henri Troyet

Russia Against Napoleon by Dominic Lieven

Napoleon's Russian Campaign by Count Philippe-Paul De Segur

The Retreat From Moscow by R.F. Delderfield

The Shadow of the Winter Palace by Edward Crankshaw

The Crimean War by Orlando Figes

Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear by Richard Connaughton

In Wars Dark Shadow by W. Bruce Lincoln

Nicholas and Alexandra by Robert Masse

Rasputin - The Holy Devil by Rene Fulop-Miller

Black Night, White Snow by Harrison E. Salisbury

Red Mutiny by Neal Bascomb

In the Russian Ranks by John Morse

The Russian Revolution by Alan Moorehead

The Russian Revolution by Ira Peck

The Ignorant Armies by E. M. Halliday

Ivan's War by Catherine Merridale

Iron Curtain by Anne Applebaum

The Bridge At Andau by James A. Michener

The Russians by Hendrick Smith

Mig Pilot by John Barron

Night Letters by Rob Schultheis

Afghanistan - The Bear Trap by Mohammad Yousaf

The Great Gamble by Gregory Feifer

Afgantsy by Rodric Braithwaite

One Soldier's War by Arkady Babchenko

The March of Muscovy

"What man ever thought or divined that Moscow would become a kingdom, or what man ever knew that Moscow would be accounted an Empire?"

An ancient wonderment from The March of Muscovy (1948) by the prolific chronicler of ancient history, Harold Lamb.

Lamb begins with the unofficial founding of Moscow in 1155 when the first building was erected on a wooded height above the river Moskva in an unknown land called Rus.

Burned down from time to time, Moscow managed to rebuild and survive 300 years of repeated invasions and servitude from both east and west while carrying on a spirited rivalry with the city of Kiev.

The majority of the work concentrates on the reigns of Ivan III (1462-1505), who is credited with founding the Muscovite state, and on the accomplishments of the otherwise demented Ivan IV The Terrible (1533-1584), who turned a provincial state into an empire.

The work concludes with short discussions on the conquests of Siberia (1579), the Ukraine (1602), and the Kamchatka Peninsula (1650).

Ivan III and IV

To expand on Lamb's work, Ian Grey's Ivan III and the Unification of Russia (1964) is a short but informative volume.

Ivan III (1462-1505) used a mix of patient diplomacy and, when necessary, brute force to consolidate local hegemony over a number of independent principalities and their Tartar allies.

Wars with Sweden, Lithuania, and the fading Golden Horde created the first true Muscovite state that extended beyond Moscow to Smolensk in the west, north to the Barents Sea, and beyond the river Pechora to the northeast.

Ivan's grandson, Ivan IV (1547-1584), became one of histories most demented rulers.

Author Henri Troyet examines this long and bloody reign in Ivan IV The Terrible (1982).

Born in 1530 to a clap of thunder, Ivan IV, and his younger brother Yuri, were so abused as children by the boyers who ruled in their stead that Ivan became a violent, sadistic psychopath who enjoyed joining in on the torture of his victims, especially those he knew to be innocent.

Ivan had entire villages, towns, even cities razed to the ground, and murdered his own son in a fit of rage.

Yet, despite the burning of Moscow once again by the Tartars (1571), Ivan managed to extend Russian influence against the Tartars of Kazan and the Crimea.

By the time of his death, he was still fending off attacks from the west by armies of Poles, Germans, and Swedes, but he had advanced Russia to the Urals in the east.

Siberia

I own, and have read, a 1000-volume library - most of it non-fiction.

Benson Bobrick's East of the Sun - The Epic Conquest and Tragic History of Siberia (1992) is one of the best. It should be read for no other reason then it is a great story well told.

With early sixteenth century Russia hemmed in by Poland and Sweden to the west and the Crimean Tartars to the south, the only route open for those fleeing repression, taxes, famine and debt, for religious dissenters, tramps, bandits and adventurers, lay to the northeast, into the vast virgin woodland beyond the Ural Mountains.

In 1581, Russian hero Vasily Timofeyovich, "Yermak", a bandit by trade, was sent on an official punitive expedition to reign in these malcontents.

A pattern was established: When the state taxman arrived, the locals pulled up stakes and moved further into the interior. Thus, over the next 100 years, with more interference than help from Moscow, thousands of square miles of the richest resource area on the planet was slowly occupied.

This exploration and exploitation was not without price, especially for all the native peoples who were ruthlessly slaughtered, subjugated and cast aside.

This was the story I thought was getting when I bought The Shaman's Coat (2002) by Anna Reid, supposing the subtitle - A Native History of Siberia - an accurate description of the contents.

Unfortunately, despite Reid's Masters Degree in Russian History, there was precious little of it.

Each chapter concentrates on a different Siberian people - the Khant, Buryat, Tuvans, Sakka, etc. - and does begin with a brief history of their initial meetings and dealings with the Russians.

From there however, the bulk of the work is made up of seemingly random interviews, stories and antidotes used to portray their sad contemporary lives and their struggle to gain the mineral rights to their ancestral lands.

Badly overwritten, it is more an exercise in self-serving literary prowess than the actual telling of a coherent story.

To conclude with Bobrick, he ends on a hopeful note on the possible future of Siberia, but also includes a long chapter on the sad history of Siberia as the frozen prison camp for Russian dissidents.

Of course, for a thorough history of Siberia as a vindictive Russian punishment, there is Alexander I. Solzhenitsyn's massive three-volume study: The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956.

Solzhenitsyn mixes his own experiences with those of contemporaries, historical figures, events and victims, to tell a complete history of the camps.

Volume I (1973) deals with the arrest and arrival in the Gulag.

Volume II (1974) describes the various camps and life within them.

Camp uprisings, changes with the death of Stalin, and the resilience of the human spirit fill Volume III (1976).

At 600-plus pages apiece, they can be a slog at times, but worth the read.

Peter the Great

One hundred years after the terror of Ivan IV, came the relatively enlightened rule of Peter the Great (1682-1725) who dragged a medieval Russia, often kicking and screaming, into what was the modern European world.

Author Robert Masse presents a panoramic work that, like Bobrick, should be read just because it is a great story well told: Peter the Great - His Life and World (1980).

Soon after taking power, Peter traveled to Europe, and by apprenticeship, personally learned every detail of ship building so to build a great navy.

He built St. Petersburg, revised the law, and modernized an army he led to battle in the far off Crimea.

Except for frequent bouts of festive drunken revelry that often lasted for days, he seems to have been in constant motion.

I, for one, am in awe of people like Peter. All of his accomplishments were achieved at a time when every aspect of daily life required a physical effort. Life was conducted on foot or at the speed of a horse. A simple letter to another part of the far flung empire might require a round trip of months.

That he accomplished so much under such circumstances is amazing.

For those interested in the times without the massive read of Peter the Great, there is Russia in the Era of Peter the Great (1969) by L. Jay Oliva.

You could say a primer to Masse's work, Oliva touches on the political, military and social lives of both Russia and Europe in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Catherine the Great

Sophia Augusta Fredericka, the future Catherine the Great, was born four years after the death of Peter the Great.

German born and French educated, Catherine, at age 16, was married off to the feeble Russian Grand Duke Peter III who, when informed of his marriage bed duties, "... sniggered and was afraid."

The Grand Duke never recovered from the shock and was murdered soon after taking power, leaving a reluctant Catherine to rule over a nation she never really understood.

With Catherine the Great (1977) author Henri Troyat, as with his Ivan the Terrible, dwells on the more sensational aspects of the reign - the affairs and intrigues of the court, of which there were many.

A woman of substance, Catherine personally led the army, sword in hand, to quell a coup d' Etat soon after taking power.

She revised Russian law, and squashed an insurrection of the poor led by the Cossacks.

She fought wars with Poland, Sweden and Prussia, wrested the Crimea from the Tartars, and annexed a large portion of the Ukraine.

Spoiler alert: After 34 years of rule (1762-1796), she died as did many of the monarchs of the day - fat and degenerate.

Russia Against Napoleon

Not 20 years passed between Catherine's death and the invasion of Napoleon in 1812.

I can recommend three works on the subject, all from a different perspective.

Author Dominic Lieven examines the French invasion from the Russian, mostly officers, perspective in his massive volume Russia Against Napoleon (2009).

He details the results of Peter and Catherine's conquests, the preparations for war, and the war itself - from the invasion of 1812, and subsequent French retreat, to the battle of Leipzig in Germany in 1813.

Two much shorter works are Napoleon's Russian Campaign (1958) by Count Philippe-Paul De Segur, and The Retreat From Moscow (1967) by R.F. Delderfield.

Both describe the invasion, the frightful slaughter at Borodino, the burning of Moscow, Marshall Ney's heroic rear guard defense, and the final disaster at the bridge over the river Berezina.

De Segur tells the story from a scholarly perspective, and Delderfield from the French soldier's point of view.

Russia and the Nineteenth Century

"The whole of our administration is one vast system of malfeasance raised to the dignity of state government" - A. M. Unkovsky, Provincial Marshall of the Nobility of Tver, 1859.

An entertaining read, The Shadow of the Winter Palace - The Drift to Revolution 1825-1917 (1976) by Edward Crankshaw provides a fine overall view of the last four Russian Tsars and the 100 years between Napoleon and WWI.

Internally, there were reforms in law, education and government, including the emancipation of the serfs in 1861.

Much of the century was caught up in revolutionary movements that railed against a dysfunctional autocracy - from the unsuccessful Decemberist Revolt against Nicholas I in 1825, to the eventual assassination of Alexander II in 1881.

Internationally, Crankshaw summarizes the Crimean War (1853-1856), the sale of Alaska (1867), the ill-conceived war with Japan (1904-1905), the ascendency of Lenin, and the fall of the last Tsar, Nicholas II, in 1917.

In the middle of the century, the Russian claim of sovereignty over all Orthodox Christians, no matter where they lived, was a direct challenge to Turkey.

The entire episode is well documented in The Crimean War (2010) by Orlando Figes.

The siege of Sebastopol and the Charge of the Light Brigade were two of the events in a war that did not end well for anyone.

Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear (1998) by Richard Connaughton tells the story of Russia's bumbling, incompetent bid for a warm water port at the expense of the Japanese who thrashed them thoroughly.

In Wars Dark Shadow

In Wars Dark Shadow - The Russians Before the Great War (1983) by W. Bruce Lincoln, stands with Barbara Tuchman's The Proud Tower as a vivid portrait of a way of life in Russia, and in Europe, in the last 25 years before WWI swept it all away forever.

Robert Masse's Nicholas and Alexandra (1967) is a frank, but sympathetic examination of the tragic life of Nicholas II, a man far more suited for the life of a clerk than that of a Tsar.

Devoted to his wife, he ruled without the slightest idea of life In the countryside.

Eventually, that ignorance, and the arrogance of place, cost him, his family, and his country, dearly.

A major reason for disaffection among those around Nicholas and Alexandra was the rude, unwashed, unlettered and lecherous peasant Rasputin - The Holy Devil (1928) by Rene Fulop-Miller.

A supposed holy man, Rasputin held a hypnotic sway over both Nicholas and Alexandra due to his seemingly miraculous ability to soothe the hemophilia of the couples beloved son Alexei.

Rasputin was murdered late in 1916: poisoned, stabbed, shot, and finally, pushed through the ice of the Neva river; but it was far to late to change the course of events

Events that had been simmering for some time.

In the spirit of long Russian tradition, revolution was in the air for the entire reign of Nicholas II as well documented by the brilliant Harrison E. Salisbury in his exhaustive study Black Night, White Snow- Russia's Revolutions 1905-1917 (1978).

Most of these insurrections, no matter how brave, or foolhardy, ended badly of course, as did the case of Red Mutiny (2007) when the crew of the battleship Potemkin mutinied in hopes of sparking a general revolution.

Author Neal Bascomb relates the inspiring tale of the Potemkin's 11 harrowing days of revolutionary freedom.

It did not end well for the crew, of course, but it is quite a rousing tale of heroism doomed from the start.

World War I

A picture of Russian espirit d'corps early in WWI is presented by John Morse in his entertaining In the Russian Ranks - A Soldier's Account of the Fighting in Poland (circa 1916).

An English business man stuck in Germany when war broke out, he was forced to escape east where he joined the first Russian forces he ran into.

In true English understatement, he apprises the thrill of the cavalry charge, and the clearing of a German trench.

He is obviously having the time of his life until he falls ill, is captured by the Germans, escapes, and is captured by the Russians who eventually place him on a slow boat back to England.

It is only after he is safely back in England do we discover he is 60 years old.

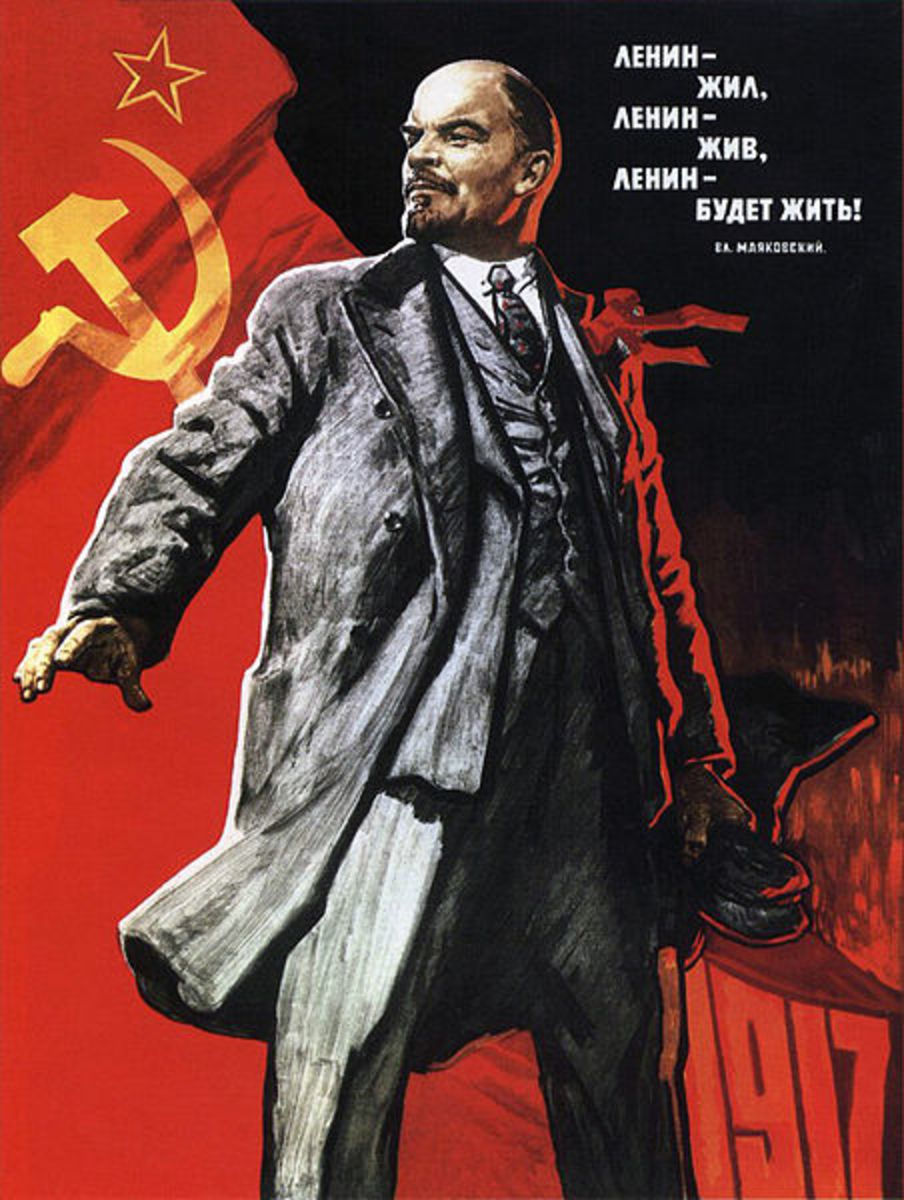

Revolution

The Russian Revolution (1958) by the able Alan Moorehead is a recap of the 20 years leading up to the storming of the Winter Palace in 1917.

I purchased The Russian Revolution (1967) by Ira Peck in 1967 from the Scholastic Book Service while still in grade school.

In paperback, and barely 100 pages, it is full of period photos.

Notably, it offers a (very) brief description of the brutal civil war that erupted after the Russian surrender in 1917.

Also included is mention of an incident the Russians have never forgotten nor forgiven.

In 1918, the American Expeditionary Force to Northern Russia, occupied Archangel and Murmansk near the artic circle.

The mission was the protect arms shipments from falling into the hands of the victorious Germans.

One misunderstanding led to another, battles were fought in the bitter cold, lives were lost, and eventually the Expeditionary Force was withdrawn.

The entire bumbling incident is described in detail in E.M. Halliday's revealing The Ignorant Armies (1958).

World War II

Of the 50-plus volumes I have on Russia in WWII, including several, heavily edited, first person accounts, none of them provide but the merest glimpse into the life of the common Russian soldier.

Then there is Catherine Merridale's important, highly readable, and sympathetic ode to the WWII generation Russian soldier, Ivan's War - Life and Death in the Red Army 1939-1945 (2006).

Under strict military and political control by questionable leadership, and often short of supplies, an entire generation was driven forward to die in their millions.

The survivors returned to little fanfare from a depopulated country whose entire infrastructure had been destroyed.

They were told to go home and forget where they had been, what they had seen, and what they had done.

Highly recommended for students of WWII or anyone interested in what shaped the character of the Russian WWII generation who are now passing, as are our own.

The Iron Curtain

After WWII, Russia found itself in possession of large swaths of eastern Europe. They were not as popular as they had imagined.

Foiled at the ballot box, they weaseled their way into power by taking over the police, newspapers and radio, youth organizations and control of the workplace.

Pulitzer Prize winner Anne Applebaum reveals the blueprint used to subjugate the peoples of eastern Europe, and the consequences for the ordinary citizen, in her important work Iron Curtain - The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-1956 (2012).

The communist takeover of eastern Europe was not without resistance and culminated in the brutal putdown of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956.

Sympathetic author James A. Michener personally helped many Hungarians escape the final battle and relates the survivor's story in The Bridge At Andau (1957).

The Russians

"And so it was necessary to teach people not to think and make judgements, to compel them to see the non-existent, and to argue the opposite of what was obvious to everyone …" - from Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak.

Pasternak's words might serve as the theme for Hendrik Smith's highly informative The Russians (1976), a revealing first hand study of life in the Soviet Union during the early 1970's.

He examines all walks of life, from the privileged with their country dachas, to the common man standing in queue and living 'nalevo', or under the table.

He studies rural, city and political life in an atmosphere where WWII was still the defining national call to patriotism.

A look at the issues faced by the Soviets at the time; culture, religion, dissent, thoughts on the outside world, etc; concludes the work.

A massive volume, but well worth the read.

It was during this time,1976, that Soviet Air Force pilot Lt. Viktor Ivanovich Belenko deserted and flew his top-secret Mig-25 to Japan.

Mig Pilot (1990) by John Barron tells the story of Lt. Belenko - from his peasant background, his rise through the Air Force ranks, his eventual disenchantment with communism, and his struggle to adjust to American society.

Afghanistan

The Soviet Union of The Russians was the Soviet Union that invaded Afghanistan in 1979.

Perhaps the most interesting of the four volumes I have on the subject is the brief, first person account of Rob Schultheis, Night Letters - Inside Wartime Afghanistan (1992).

A newspaper reporter, Schultheis rather bravely, or foolishly, joined mujahedin raids that matched out-modeled weapons against the latest Soviet tanks, planes, and helicopters.

Another unique perspective is presented by Mohammad Yousaf (with Major Mark Adkin) in Afghanistan - The Bear Trap (1992).

A Brigadier in the Pakistani army, Yousaf was the head of the Afghan Bureau of Pakistan's Inter-Service Intelligence. He controlled the flow of US purchased arms across Pakistan and on into Afghanistan.

He follows the course of the war while explaining what it takes to fight a modern war in such a place as Afghanistan.

The Great Gamble (2009) by Gregory Feifer is told from the Soviet soldiers point of view.

The demoralization that occurred among the Russian army during Afghanistan would have devastating consequences later in Checknia.

Feifer concludes the work by comparing the Soviet failure with US efforts in 2001.

Afgantsy - The Russians in Afghanistan 1979-1989 (2001) is another interesting work.

Author Rodric Braithwaite was the British Ambassador in Moscow (1988-1992) and presents a conventional and comprehensive history of the conflict from the Russian perspective, including the negative effects it had on the men, the army and the country.

Checknia

Those negative effects from Afghanistan exploded in the Chechen wars of 1995 and 1999.

One Soldier's War is author Arkady Babchenko's brutal first person account of his time in the Soviet army.

Drafted, he and the other recruits were routinely beaten by their older superiors before being sent to the horrors of the Chechen front.

Unable to find work as a civilian after the first war, he volunteered for the second Chechen war.

The only thing worse than a recruit, is a volunteer.

Whack!

Even though it has been 20 years, with morale so low, one must wonder if the current Russian army has rebounded into an effective fighting force.

In Conclusion

In conclusion, read the books I have reviewed and you should have a working knowledge of Russian history and character - from the founding of Muscovy to the age of Putin.

Good reading!