Storyline - 17: Tall, Forgotten, Alone, Like a Sentinel Amid the Tall Trees in the Lower Dale

All there is left of the mine buildings is that chimney?

''Ey gaffer, there's been a cave-in up t'ill by Surrender Bridge, close t'smelt mill!'

The lad was out of breath, having run hard all the way from the top end. He had almost fallen headlong down the steep hill that ran along Arkengarthdale, so great was the urgency, and banged on the office door. One of the clerks was told to see what the noise was about.

'What's up lad? You look fit t' bust, d'ye want a drink o' watter?'

'Jack said to tell ye there's been a cave-in near t'smelt mill... er, inbye* I think 'e said, reyt up top end!'

The clerk turned to look at the office manager. As he did so the slightly-built boy pushed past him to stand at the manager's half-open door,

'Come quick boss! Jack's got everybody scrabblin' and shovellin' 'ard to get 'em out. There's five men buried where they'd been diggin' up that new workin' on t'moor! One o' the 'orizontal chimneys 'as collapsed an' all!'

'Tell Jack I'm on my way!' The manager lifted the speaker and wound the telephone hard. He slammed it down again and shouted through his back window at some men who had just past, 'Have you just come down from the top end?'

'Naw, boss. We're in from ower yon', one of the men pointed to the back of the town.

Reeth was normally one of the quietest towns in the Dales except for Friday night. Men and women poured out from the three public houses and hotels that faced the green, stirred by the news. A steam wagon passed the office on its way out to Muker just as Henry Truelove came out of the office building,

'Are you in a rush?' he asked the driver.

'You've got to be jokin' mate!' came the answer. Steam wagons could be passed even by a laden horse-drawn cart, surely the man knew that.

'No I'm not bloody joking! How soon can you get that contraption up this hill to the moor?'

'It'll take a while -' the driver was about to finish when someone came up from the river road with an empty cart. Mr Truelove held his hand up to stop the cart, a bit too suddenly for one of the horses. It shied and backed away. It was all the carter could do to stop it pushing him back downhill across the green.

''Ey, what is it, 'Enry? D'you want me back in t' Swale?'

'Can you take six men up to the top, Frank?' Truelove asked. 'I'll get some more in the wagon. We'll need more than shovels, mind you. Can you wait while I get someone to fetch pulleys and jacks... and does anybody know whose got some steel bars to lever rocks out of the way?'.

Jeff Todd, one of Truelove's runners prodded the air above his head,

"Blacksmith's got that kind o' gear. I'll go an' ask if we can borrow it the while".

The wagon driver cursed under his breath. He had a consignment to deliver to the pub landlord at Muker but realised he wasn't going to get out of this so he set his gears to go uphill on the steep incline. He yelled to Truelove above the noise of his wagon, the clanking chains and the hubbub of the market square in front of the Black Bull and the King's Arms. Men yelled and women screeched at the news, fearful it was their husbands who might have been crushed. Children dashed about, mouths wide open, some yelping like hearth dogs. A line of onlookers crowded the green as another cart was hauled uphill by a team of four as fast as the gradient allowed.

'Well get your body on 'ere. 'Oo else is comin'?' Truelove did not have long to wait for volunteers. Before long the steam wagon chugged upward and onward. .

By the time the two carts and the steam wagon reached the top and had negotiated the sharp bend down from the road to the mine settlement most of the villagers from Langthwaite were already there. Some of the menfolk there worked for the company, there being fewer farming jobs now with increased mechanisation.

Truelove pushed past an army of onlookers. They were watching men come down the hillside, slithering on broken stones with stretchers slung between them, trying hard in the drizzle not to dump the wounded men out of the rocking stretchers. Darker clouds loomed from Rogan's Seat to the west, out of sight now in the failing light. It would be dark soon, and colder weather threatened from the Pennines.

'Henry, have you heard?' One of the deputies pushed toward him through the crowd.

'That's why I'm here, Simon. What's happened?'

'The rock was unstable. They're the first two to come down. I warned Mr Peabody that part of the hill was tiable to subsidence, but he wanted what was there - everything that could be dug out', Simon Hepplewhite answered. He had mining experience and from experience saw the writing on the wall for the Peabody Mining and Quarrying Company in this part of Swaledale.

Peabody was young, headstrong. He saw his lifestyle threatened and he wanted to mix with the other young blades at the Black Bull. He was also newly wedded, and foresaw his son inheriting the business he had inherited from his grandfather. He was therefore bullish in his dealings with those who worked for him. Henry Truelove had felt his scorn more than once, when young Peabody showed with his new bride in tow, trying to show how steely he could be..

Now men had been injured, or even killed, would Peabody see reason and cut his losses? Somehow, Truelove doubted that. They were dealing with a man who knew little about mining or the Dales geology. He only knew how to spend the proceeds, not really a chip off the old block.

Peabody showed up at the site the following morning. Men were still trying to recover the bodies of two miners, but no hope was held of finding them alive. The young mine owner stamped his feet to warm himself. He had been driven there by Hepplewhite straight after breakfast, and the kedgeree he had eaten nearly came back up again when he saw one of the miners borne past him to the ambulance.

'For God's sake pull the cover over him!' Peabody yelled at the stretcher bearers.

'He isn't dead yet', the ambulance man answered flatly.

'Who's that?' the man on the stretcher asked weakly.

'It's the boss', another man told him.

'What, Truelove?'

'No, higher up', he was told. Hepplewhite, standing beside Peabody knew all the miners. He knew their families and he knew their wives. Living on the parish was not living, and rents had to be paid. Land owners were no more charitable than mine owners, and there would be the few sticks of furniture stacked outside - whatever the weather - ready to be carted away. There was little enough work up here, but if a man couldn't work because of injury...

The man eased himself up onto his right elbow and told the stretcher bearers to stop. Then he looked to where Peabody stood, looking uphill at the next two struggling down in the flurry of snow that almost hid them from time to time.

'Peabody!'

The young man spun around, still hugging himself in the cold. He mouthed 'what?'

'Peabody, think of yourself as cursed!' The man said no more and fell back into the stretcher, his bearers hurrying back to their vehicle. They had a long drive in the worsening weather, back to Barnard Castle, the nearest town that could offer medical care.

'Who was that?' Peabody stared after the stretcher.

As the following stretcher passed him, and the bearers pulled back the cover to show the young man under it was dead, Hepplewhite nodded and answered,

'That was old Matthias Collier'.

'Collier?' Peabody smirked. 'He's in the wrong business, isn't he?'

'So are you', Hepplewhite said into the icy wind.

'What was that?' Peabody strained to hear.

'Nothing, sir', Hepplewhite walked to the ambulance. He asked the men as they pushed the stretchers into the back, 'Is that all of them?'

One of them, the driver shook his head and walked forward to the cab. As he got in he said somebody had told him there was another missing, but they couldn't be sure.

Peabody turned to Truelove, standing beside him, looking at the dark clouds dropping down from the west. Rogan's Seat was lost in there, somewhere, all two thousand feet or so of it. As the ambulance pulled away one door came open and the driver braked hard. His assistant leapt out and ran to the back to slam it shut again. Before he could do so Matthias croaked as loud as he could,

'When t'sun shines in November on Great Pinseat, another Peabody shall lose his feet!'

'What was that about Great Pinseat?' A shaken Peabody asked Truelove.

'Nothing, sir. I think he was delirious', Truelove saluted to the ambulance driver on his way back to the road, pushed by several burly miners to get it on its way up the slope.That would be the last they saw of Matthias Collier, but not the last they would hear of him.

Peabody ordered the demolition of the mine buildings after reading the report Truelove sent him. It would cost more to sell the lead from there than they would make from it. Cheaper foreign imports would signal the end for Swaledale's lead industry, as it would in the same decade for anywhere in the North.

Yet, when the demolition crews knocked down the walls of the Collier cottage one chimney stood. The weather was closing in again and it was thought the chimney would be down within the year. So they left it. The Forestry Commission bought the land, conifers were planted, a cash crop of trees to replace those felled to make pit props for mines all around the country. Peabody had shares in the forest, after all he had owned the land mined for lead.

His son owned the shares after him. One day he took his young family with him up Arkengarthdale to see the site his father told him had been blighted by a mine incident, as his father told him. His wife set out a picnic for him whilst he went to look. The day was warm for November, and his children felt adventurous. They ran ahead, through the footpath gate, out of sight. Their father looked up just then when the sun came out from behind a fast moving cloud. Great Pinseat was picked out by a bright, broad shaft of November sunlight.

Peabody heard a high-pitched scream before he came to where the mine cottages had been. He ran to where his daughters shuddered. Behind them a chimney wall had collapsed, large stones lying on his son's legs.

The ambulance was a long time coming from Barnard Castle. It came down the track from the road and halted near the gate. The driver and his colleague followed Peabody's wife and daughters to where her husband nursed his son. Their worst fears were realised when they visited the hospital in Northallerton he had been moved to. The lad would walk again one day... on metal legs.

Up at Langthwaite a group of walkers left the road to follow the forestry track.

'Did you hear that?' one said.

'What was that?' a second asked. 'It sounded like an old man laughing'.

------------------------------------------------------

*Inbye: underground - in this case in the lead seams.

This story is set in what was the North Riding of Yorkshire, known since the 1974 boundary changes as North Yorkshire

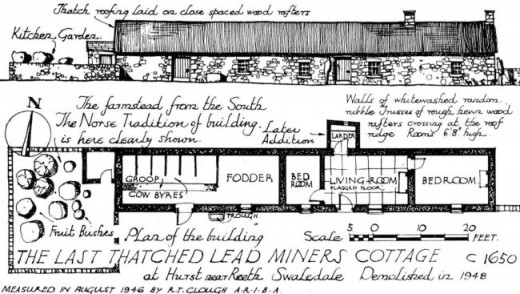

The location is near Reeth in Swaledale, up the dale from Richmond. The lead mining activities were divided into 'drifts' that punctuated hillsides, nearby smelt mills processed the lead ore and gave off poisonous fumes, mostly taken away by 'horizontal chimneys', stonework formed into long culverts up the hillsides. In this case the fictional accident happened near the smelt mill close to Surrender Bridge, off the road between Feetham in Swaledale and Langthwaite in Arkengarthdale

Arkengarthdale near Reeth, North Yorkshire

Click on the map, click on 'Satellite' and navigate from the pointer 'A' on the map northward out of Reeth along Arkengarthdale

At the foot of Arkengarthdale... Reeth, the lead town

Swaledale was near the epicentre of Dales lead mining.

Upper Swaledale was one of the centres of Dales lead mining, Reeth and Grinton were it's 'capitals'. Walkers can see the remains of lead mining all around, as I have mentioned in the early Hub-pages of my TRAVEL NORTH series on the Dales. Mine buildings still stand here and there. I've driven off the Catterick to Askrigg road near Bellerby (Leyburn) and stopped by one of the still standing chimneys. There's what's left of the smelt mill by the track and an 'horizontal chimney', a stone-built duct that took the lethal fumes to the base of the chimney and out of the top. There may have been other horizontal chimneys here, but much has gone, possibly taken for walling elsewhere. Buildings, or rather ruins, can be seen everywhere away from the roads, along the Coast to Coast walk route and as far north as eastern Cumbria near the boundaries with County Durham and North Yorkshire.. Take look in the book here, YORKSHIRE DALES ADVENTURE,GUIDE (or - if you can get it - Arthur Raistrick's book, 'Lead Mining In The Dales')