Set Me Free--An Excerpt (Non Fiction)

All Names Changed

Set Me Free

"Freedom is not worth having if it does not include the freedom to make mistakes."

--Mahatma Ghandi

She was not my patient, and when I was called to witness the atrocity that was the buzz of our unit, I was immediately struck by the baldness of her head. Her name was Monji and she had recently arrived as a refugee from Liberia. In the language of the freed African slaves who were the countries original settlers, the name Liberia means liberty. Monji was in active labor, and she was silently walking around the room. A great deal of land separated her from the children she’d birthed before the camp. We did not know her language, and she did not speak ours. Our language line services for translation were not able to accommodate her specific dialect.

She was beautiful, with skin that glistened like a creek in the middle of night. She was so dark, a soul could get lost in the blackness of her. She was puzzled by the spectacle she had become.

The atrocity, as best could be determined, was that she intended to have her child on the hospital floor. She’d had her other children on the earth, and it seemed only right to her that the hospital’s floor was the best available substitute. The robotic contraption of a bed that all the people in blue scrubs wanted her to get in seemed like madness to her. She was wordless, but her expression, and the language of her body was clear and direct. Why are all these white people looking at me? Don’t they know how to have babies in this country? Why is this string in my arm?

In time, a family member made her way to the room, and was able to help bridge the insurmountable communication gap between the patient and our staff.

“She wants to deliver on the floor. She does not like so many people looking at her in pain,” the woman called herself Monji’s sister and said this calmly.

I noticed that Monji and this woman did not look remotely like one another. This could easily be missed by anyone, and everyone, who hadn’t thought to look past their darkness for the individuality of their features. I imagined that at some point in their lives, in the hardship of what their lives had been, that they had become sisters related by the passion to survive.

Her primary nurse was distressed about the very thought of a non-labor bed delivery. She was rattling off all the hazards she could think of, like a chapter from an obstetrical medicine textbook. The nurse, and most of the residents responsible for this woman were completely beside themselves. They were concerned for her, and for her baby. What the patient had going for her case to have this baby the way she wanted, was that she had what we call in this field a "proven pelvis." This meant that she’d had children vaginally before, and assuming she was carrying a fetus that was not exceptionally big, she would likely be able to do so again without much incident.

Monji continued to walk around the room, massaging her belly, shaking her head at the pain, her eyes were strong and meek. Her fear was obvious, but what was also clear, was that her fear had nothing to do with having this baby. She’d done this before, and likely, she’d helped other women do this before. She was afraid of us,. The people in the blue scrubs with the disagreeable faces clearly looking down on her primitive way of having a baby. She wasn’t trying to cause trouble, she was too scared to. She wasn’t digging her heals in, and demanding control the way a patient who spoke English might. She was finally in a free country, and hadn’t learned what that meant yet, but was hoping that it didn’t involve being forced into a bed she did not understand, to do something she did understand. We called it safety, hospital policy, and we called it civilized to deliver our way, in our bed, and in our mechanical stirrups. But the message was clear, that even in this country, control of a woman came easier on her back with her legs up.

We learn in school, at conference, in the textbooks, and in practice, that our best maneuvers when we need to rescue a baby in a vaginal delivery are done in the traditional stirrups position. We tend to appreciate epidurals, mainly because we don’t like to witness suffering. We also like epidurals because if things turn south in a delivery, our maneuvers will become more abrupt and fierce, and we do not want to cause undo pain. In emergent situations, it is far easier for trained professionals to work on the problem without the added contender of excruciating pain. But for those of us who are the most honest, the mystery of childbirth, the godliness of it, is terrifying. We manage our own fear by creating the most controlled environment as possible. Whether or not they know it, a patient wants and needs their providers to function in as calm, and clear-headed a way as possible. Our delivery methods in the United States are our best effort at maintaining safety for a woman and for her child.

Monji had not yet read the US textbooks on childbirth, nor had she attended any conferences on maternal-fetal safety. What she had done, however, was have babies. A woman who’d recently come from an environment where sexual violence ran rampant, was none to keen on being manipulated into bed and strapped onto the wires that were designed to listen to the gallop of her baby’s heart. We were at an impasse. Monji’s eyes called me in a way that made me unable to look at her for very long, and they were asking for help.

One of our nurses there in Utah, made the radical suggestion that we grant her wish to deliver on the floor. She suggested the blue drape that covered the delivery table as a place for her to deliver, and made sound and reasonable suggestions about what to do to keep them safe. It was brilliant, and the residents agreed. A couple of hours later, in near silence, as if laying an egg, Monji had her baby girl on the blue drape on the floor. When Monji got a good look at her baby, nearly dry after the quick efforts of her nurse, I couldn’t help but think that the loving smile she gave her daughter looked strangely like an exchange of two co-conspirators who had loved their crime.

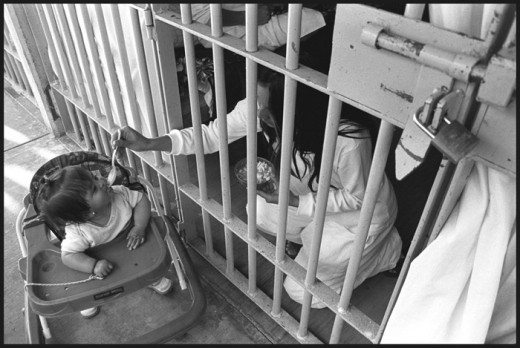

Approximately, two weeks later, I had a patient whose crime or crimes were not disclosed to me, but she was seated in our small waiting room by our unit in handcuffs. To her immediate left was a female prison guard in full uniform. Her name was Robin and she had come from the Timpanogos facility in Salt Lake. Her labor was going to be induced. When we are inducing a labor at term, most insurance companies like us to have cause. Labor inductions can be for maternal or fetal safety. Inductions can be due to a suspicion that the baby will be large for it’s gestational period, or that maternal blood pressures are becoming elevated, or for low amniotic fluid around the baby, and so forth. It is known that when there is a pregnant woman who is incarcerated, maintaining as much control of the labor as possible is ideal in order to prevent escape of the prisoner. I wasn’t sure how inmate would go over as indication for this induction, but it wasn’t my affair. I had many more questions about this patient.

She had pale skin, long brown hair and quiet brown eyes. Though she was in her early twenties, she could’ve easily been mistaken for the neighborhood babysitter in Draper, UT. She was very mild and unassuming. I noticed no tattoos, no random knife marks, or unusual piercings that said she might rob someone, or assault someone. I had the fleeting thought that if I were wrong about this, and things got ugly all of a sudden, I could probably take her. A good nurse is always thinking ahead.

When a patient is admitted to the hospital we have to take a history, which involves a series of medical and personal questions. These questions help us to take better care of the patient we have as an individual, and to understand them. What are you in prison for, is not a question on our database, but I was dying to know. She seemed so sheepish; she seemed innocent. But I knew that this would just be a question that would only embarrass her, and would not be relevant to her care.

Robin was eager to cooperate, and very appreciative of everything done for her. She moved in a way that would make a person think her name was Apology, and she had to live up to it. She declined pain medicine for most of the shift, and sans the rattle of the chain linked from the base of the bed to her right hand she would’ve been a classic mommy in labor who was coping well. The prison guard fidgeted in her chair at the foot of Robin’s bed in a bored way for most of the day. Robin certainly hadn’t made any attempts at freedom, and my suspicion was that she didn’t think she deserved it. I have an urge, as most nurses do, to make what is wrong right, or as right as it can possibly be. I encouraged Robin, smiled at her a lot, and worked to project the fact that I was not judging her, and that I would not judge her. She seemed nothing but grateful. She spoke very little, but explained to me hours later that the baby, ward of the state at birth, would go to a family member eventually.

I gave report on Robin to the night shift nurse at 7pm, before Robin’s baby was born. She still had a long way to go to see her baby, but I let myself wonder about her past on my drive home. This woman couldn’t have planned to have a stone-faced prison guard be her labor coach. Where was the father of the baby? What on earth had she done to be in that situation? And when she was a little girl, dressing dolls, or building blocks, who would ever have thought that she would end up chained to a labor bed having her labor induced? Who would ever plan to have their first words to their healthy baby be about saying goodbye in this way?

I will never know Robin’s full story. What I did learn was that nearly 70 percent of female inmates report a history of victimization either physically, or sexually before they were imprisoned. I learned that the criminal mind is a complicated one, and that before it was a criminal mind it was likely a mind similar to mine, yours and our neighbors. I learned that for many women, something got broken inside, and before it got fixed crime came first. Violence begets violence, abuse begets abuse, and the self-image that sprouts from so injurious a seed as victimization, is an obvious culprit for so much of what is seen behind bars. At dinner, on the 5 o’clock news, Robin would’ve been some irresponsible, reckless and hopeless deviant. But as the woman by her bedside for most of the day during her labor, the show was quite different. Robin in actuality, was a very lost woman, chained to the bed, and chained to her past who just wanted to be set free.