The Mighty Fitz

By: Wayne Brown

(Writer’s Note: In August of 1976, Canadian singer/songwriter, Gordon Lightfoot, release the song, “Wreck of The Edmund Fitzgerald” commemorating the loss of the big iron ship and its crew on Lake Superior during a November storm of 1975. The song tells a great story and relates very well to the facts of this true occurrence. I thought it might be interesting to lay out the lines of verse contained in the song and correlate them to what was happening in the real life tragedy that occurred on that fateful day of 10 November 1975.)

The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

As written by: Gordon Lightfoot

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake they call Gitche Gumee

A subset of the Chippewa Indian tribe settled near the shores of the Great Lakes specifically in the Michigan and Wisconsin regions. These bands were Ojibwa Indians. Their folklore and legends incorporate stories which relate to the lakes. The Ojibwa referred to one large body of water as Lake Gichigami . French explorers had labeled the lake as La Superier . The term Gichigami translates to English as “Big Water”. It was first seen in writings by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in “The Song of Hiawatha” written as “Gitche Gumee ”. The French reference to “La Superier” is thought to point to the fact that this particular body of water rests above the other lakes.

The lake it is said never gives up her dead

When the skies of November turn gloomy

The Great Lakes and especially Lake Superior have become legend for swallowing up ships and boats in the winter storm season. More than 300 shipwrecks are estimated to reside in the deep waters of the lakes most finding their way there due to conditions encountered on the lakes in the winter storm season. Lake Superior covers a land mass approximately the size of the State of South Carolina measuring roughly 350 miles by 160 miles in dimension. Superior is over 1300 feet deep in some areas and can easily swallow a vessel so deeply that it cannot be salvaged. Superior is the largest fresh water lake in the world although not the deepest. Even at summer time temperatures, the average water temperature is 40 degrees F. In the winter months, the water temps drop significantly and become very unforgiving to any poor souls entering the water for even short periods of time.

With a load of iron ore – 26,000 tons more

Than the Edmund Fitzgerald weighed empty

The Edmund Fitzgerald was put into service in 1958 as an iron ore transporter on the Great Lakes. Iron ore or taconite is pelletized for shipping in large bulk quantities. The Edmund Fitzgerald was a classic bulk freight design looking somewhat similar to an oil tanker with most of the hull area configured into compartments for the bulk materials. There were individual accesses to each of these large cargo bays on the top deck of the vessel and walkways below the deck which allowed interior access to each bay. The pilot house and controls were placed forward on the keel of the vessel with the cargo bays distributed from the keel to the stern in order to balance the center of gravity of the vessel and provide for maximum visibility for piloting the ship. The Edmund Fitzgerald was capable of hauling 26.6 tons of dry bulk ore as configured. Fully loaded, the ship sailed at just over 40 tons of gross weight.

That good ship and crew were a bone to be chewed

When the gales of November came early

The Edmund Fitzgerald was commissioned for build by the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company. It seems the company’s president at the time was the son of an old sea captain and thus he guided the insurance company to invest in a great lakes freighter. The ship was aptly named after the old sea captain, Edmund Fitzgerald. The stipulation at the time of build was that the ship would be the biggest or among the biggest freighters on the lake. Certain restrictions set forth for governance of the St. Lawrence waterway would define the limits of the ships size. The ship measured 729 feet long, 75 feet wide, and had a depth of 39 feet. It was powered by a Westinghouse 2 cylinder steam driven turbine, coal-fired engine driving a 19.5 ft. single propeller. The engine created over 7500 horsepower. The pilot house was located forward on the keel and the engine house was located rearward to the stern. The area in between was designated as the cargo hold made up of multiple water-tight compartments. The Edmund Fitzgerald was capable of speeds under load of 14 knots. In 1972, the ship was retrofitted to burn fuel oil rather than coal as its source of power. The ship required 29 crewmembers for operation and true to plan was at one time the largest freighter on the Lakes. The Great Lakes begin to see the heavy impact of winter normally by late November into early December. By this time, large winter storms which have been brewing over Canada begin to drop down onto the lakes bringing heavy ice, snow, gale force winds, and heavy seas. Some sailors describe it as the wind-swept torrents of hell. The Edmund Fitzgerald had set out on this shipping leg in the afternoon of November 9th. It was early in the month thus the storm season was not yet expected although the National Weather Service was predicting a storm would pass that night to the south of the Great Lakes but really posed no threat to shipping.

The ship was the pride of the American side

Coming back from some mill in Wisconsin

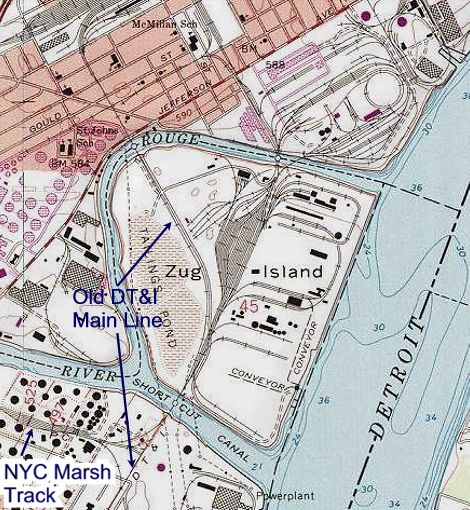

As indicated above, the Edmund Fitzgerald, also known as the “Mighty Fitz”, “Big Fitz” and “The Fitz” was owned by Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company. It was operated by the Columbia Transportation Division of Oglebay Norton Company which was headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio. The ship was registered in the United States. The Fitz had departed the Burlington Railroad Docks, Superior, Wisconsin at 2:15 PM on November 9, 1975. On this trip, it was headed to drop a load of taconite at a steel mill located at ZugIsland near Detroit, Michigan. The leg would require an overnight transit so The Fitz would be expected to arrive at ZugIsland on the 10th of November 1975.

As big freighters go, she was bigger than most

With a crew and the Captain well seasoned.

As stated above, when commissioned The Fitz was the largest freight on the Great Lakes. By 1975 other large freighters had gone into service but the Fitzgerald was still among the largest of that inventory. When the ship departed Superior, Wisconsin, it was under the command of Captain Ernest M. McSorley along with an experienced crew of 28 seamen ranging in age from 20 to 63. McSorley was a Canadian by birth but had moved as a child to the United States with his parents residing in Ogdensburg, New York which is located on the banks of the St. Lawrence Waterway. McSorley basically grew up dreaming of becoming a ship captain and he made the dream come true as he entered his adult years. By the time that he assumed command of The Fitz in 1972; McSorley had captained nine different ships and had over 40 years of experience as a mariner. McSorley had just turned 63 years of age and was sailing his last season on The Fitz. He was a man of few words yet viewed by most of his contemporaries and his crew as a skilled seaman and capable captain. He had a highly respected reputation for taking on bad weather upon the seas and dealing effectively with it.

Concluding some terms with a couple of steel firms

When the left fully loaded for Cleveland

In this case, Lightfoot adopts the concept of poetic license, in that The Fitz was departing Superior Wisconsin loading from the Burlington Northern piers. Its destination on the 10th of November was a steel mill located on ZugIsland in Lake St. Clair near Detroit Michigan. Technically, in order to arrive there, The Fitz would indeed have to set a course that was in the direction of Cleveland. First it would depart on Superior eastbound heading to the waterway locks at Sault St. Marie. At this point, the ship would transition from Lake Superior to Lake Huron and sail to the southeast and south toward Port Huron Michigan of the shores of Lake Huron. At that point, it would enter the St. Clair River and sail southbound into Lake St. Clair and then into ZugIsland. For the entire transit of Lake Huron, the ship would be pointed in the direction of Cleveland thus the poetic license on the part of Lightfoot. Also, the headquarters offices for the vessel’s operating company were located in Cleveland. The Fitz did depart on the afternoon of 9 November 1975 with a load of iron ore (taconite) pellets weighing in at just over 26,000 tons thus she was fully loaded.

And later that night when the ship’s bell rang

Could it be the North Wind they’d been feeling?

The Fitz had departed the Burlington Railroad Docks at Superior Wisconsin at 2:15 PM on 9 November 1975. After departure, The Fitz joined up with another vessel, “The Arthur Anderson” which was sailing out of Two Harbors, Minnesota heading to Gary Indiana. The Fitz and The Anderson would sail along the same route through the locks at Sault St. Marie and southward finally splitting as they neared their individual destinations. Weather was not anticipated to be a significant factor on the voyage as the National Weather Service was predicting that a storm would pass to the south of Lake Superior by the 7:00 AM hour on the morning of 10 November. This storm was expected to clear the normal sailing channels before either The Fitz or Anderson entered into Lake Huron. The Fitz had trailed the Anderson until after midnight on the 9th. Capable of higher speeds, The Fitz took the lead position around 1:00 AM in the early morning hours of 10 November. By this time both ships were encountering a massive winter storm with heavy snow, winds near 60 mph with gusts to 100 mph, and waves on Lake Superior reaching heights of 35 feet. Visibility was getting poorer by the minute and McSorley was also having difficulty keeping The Fitz at top speed. The Weather Service issued a gale force bulletin for Superior and both ships altered course toward the Canadian shore in the hopes of gaining some relief from the storm. No doubt, at this point, they were feeling the north wind.

The wind in the wires made a tattletale sound

And a wave broke over the railing

The winds had reached gale force with gusts nearing 100 mph. The waves driven by the winds were growing size. Around the cargo deck surface of The Fitzgerald, the deck rails were formed by cables strung tightly through posts placed at intervals along each side of the deck. The heavy wind gust would create howling sounds as it passed between the cables. Soon waves were breaking over the railings which stood close to 40 above the water level of the ship. Both the amount of wind and the high seas driven by it were very unusual for this early time of November. Those listening to the radio frequencies knew that it had to be bad when McSorley agreed to alter course for relief in that the captain was known to take his storms head on most of the time.

And every man knew as the Captain did too

T’was the witch of November come stealing

These were seasoned sailors who knew clearly what they were encountering. The season weather which came to the Great Lakes in late November had showed up early. In fact, one captain who had departed the same docks as The Fitz had already seen enough to head for the north shores of Superior for protection from the storm. McSorley and company had seen and encountered this type of weather before. It was not something they were incapable of dealing with but they needed the vessel to remain sturdy in the process. The witch of November was the big Canadian storms seen on the lakes every year.

The dawn came late and the breakfast had to wait

When the gales of November came lashing

By 7:00 AM on the morning of 10 November, the skies were still dark as Lake Superior was under what the National Weather Service was now classifying as a storm with sustained winds of 58 MPH and rough seas. Both The Fitz and Arthur Anderson had altered course to move toward the Canadian shoreline in the hope of gaining some relief from the storm whose center lay more to the south of their position. By this time McSorley had brought all the hands off deck. The vessel was secured for passage in rough seas. By this time, the Soo Locks at Sault St. Marie were closed due to the rough seas. The ships would have to wait out the storm, then head south toward Whitefish Point and then begin their approach for locks passage. The storm was moving rather slowly and skies remained overcast well into the day.

When afternoon came, it was freezing rain

In the face of a hurricane West Wind

By 3:00 PM, McSorley knew the Fitzgerald was in trouble. He reported on the radio that he was taking on water and the ship was listing to port or the left side. His bilge pumps were running in an effort to stay ahead of the water. There was no indication that anyone knew the source of the water although some speculate that broken hinges on some of the cargo bay doors may have allowed water from waves passing over the deck to invade the dry cargo holds creating the listing in the vessel. McSorley had reduced the RPM level of his engine as he reported that his ship was working very hard. He indicated to The Anderson captain that he was having trouble keeping under the current conditions referring to the effects of winds, seas, and the listing of the vessel due to unknown factors. The freezing rain added addition hazards associated with weight. Given enough ice loading on the high structure of the ship with the high winds and capsizing could become a reality. McSorley gave the order, “Don’t allow nobody on deck!”

When supper time came the old cook came on deck

Saying fellows it’s too rough to feed ya

The storm was relentless and continued into the evening of the 10th. All activities were shutdown on The Fitzgerald including cooking and eating. The waters were just too rough to safely allow it. McSorley had things buttoned down and he planned to remain in that configuration until they could gain some relief from the storm. The listing continued to the port side and now McSorley was reporting that he had lost his radar capability thus was sailing blind. He requested that the Arthur Anderson move within range and use its radar to help guide The Fitz toward the northern shore.

At 7 PM the main hatchway caved in

He said fellows it’s been good to know ya

By 5:00 PM, McSorley, with the assistance of The Arthur Anderson, had The Fitzgerald on a course running toward the Whitefish Point light beacon. The light was operating but the radio beacon was still out as a result of the storm. By this time, McSorley was reporting that both of his radars were out and that he was witnessing seas like he had never seen before. The Edmund Fitzgerald never issued a distress call and McSorley broadcast his last know transmission about 7:10 PM on the 10th when he reported, “We are holding our own.” At that point, The Edmund Fitzgerald essentially disappeared from the radar of other vessels and no longer responded to radio queries. Lightfoot goes to the obvious and assumes the crewmembers said their goodbyes to each other.

The Captain wired in he had water coming in

And the good ship and crew was in peril

As stated above, by 5:00 PM on the 10th, The Fitz was reporting a heavy list to the left, water entering the cargo bays, inoperable radar, and seas which in the words of Captain McSorley nothing like anything that he had ever seen in his life. Though the captain was not declaring an emergency, it is easy to see that the ship and crew were indeed in peril.

And later that night when his lights went out of sight

Came the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

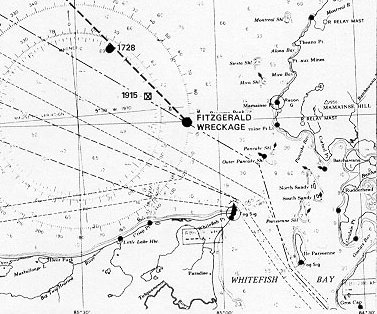

Based on communications the Edmund Fitzgerald broke up on the surface and sank approximately 17 miles from Whitefish Point on Lake Superior in 530 of water. This must have occurred shortly after McSorley’s last radio transmission at 7:10 PM on the 10th.

Does anyone know where the love of God goes

When the waves turn the minutes to hours?

This is my favorite line in the entire song. This line is in reference to the amount of time that it took to get some help on the scene of The Fitz’s loss. The Captain of the Arthur Anderson first sent out a distress call on the ship’s radio at 7:39 PM after losing all contact with The Fitzgerald. He received no response to his call. By 8:32 PM, the captain was on the radio pleading with anyone within the range of his voice to assist. He was trying to convince the U.S. Coast Guard that The Fitzgerald was indeed missing from the surface and gain a response. At the time, elements of the Coast Guard in the local area were assisting in another emergency due to the storm. Coast Guard officials later indicated that they took the report seriously but did not classify it as an emergency at that point. Considering the rough seas, the freezing rain, and the possible low water temperature, it was obvious by this time that a sailor in the water was doomed by potential exposure or drowning. Thus if there were survivors, they must have decided that God had surely abandoned any effort to rescue them in the short term. The search was left to the freighter traffic in the area as the Coast Guard did not have sufficient equipment in the area for this type of rescue. By 10:00 PM, the Coast Guard had launched a fixed-wing search aircraft to assist in the search. By 1:00 AM on the morning of the 11th, a helicopter was added to the search as well. Hours were passing rapidly with no sign of life in the water.

The searchers all say they’d have made Whitefish Bay

If they’d put fifteen more miles behind her

The Edmund Fitzgerald sank in deep waters some 17 miles (15 nautical miles) off of Whitefish Point. Had McSorley been able to acquire the lighthouse reference on the point, The Fitz may have been able to sail into Whitefish Bay and gain some relief from the storm. Instead the large freighter broke up and rapidly sank to a deep water grave in Lake Superior.

They might have split up or they might have capsized

They may have broke deep and took water

While there is considerable speculation as to why The Fitz sank, no one is totally sure of the cause. The best estimates based on visits to the wreckage by underwater submersible vessels state that The Edmund Fitzgerald broke up on the surface and sank in two pieces to a depth of 530 feet coming to rest on the floor of Lake Superior. This breakup could have been caused by the weight of the additional water and ice taken on board in the storm or it could have been the result of other incidents which created damages in the ship. At the time of the loss, the ship was valued at $24 million dollars. The financial loss still stands as the largest to ever occur on the Great Lakes.

And all that remains are the faces and the names

Of the wives and the sons, and the daughters

There were no survivors from The Edmund Fitzgerald. There were no bodies recovered from the seas so the speculation is that the breakup occurred so rapidly that none of the crew was able to escape the main body of the ship. All 29 crewmembers went to the bottom of the lake to remain in a dark watery grave at 530 feet below the surface. The only real evidence of their lives is the relatives they left behind who were waiting at home for their return.

Lake Huron rolls, Superior sings

In the walls of her ice water mansions

Old Michigan seems like a young boy’s dream

The islands and bays are for sportsmen

The upper Great Lakes have a personality all their own ranging from the frequently rough waters of Huron and the beauty and sport of Michigan to the icy waters of Lake Superior which even in summertime seldom rise above 40 degrees F. Given the beauty and recreational appeal of the lakes and the area surrounding them, one must be reminded that this is also an area of potential danger especially in terms of stormy weather for water vessels. Death lurks just beneath the surface.

And farther below Lake Ontario

Takes in what Lake Erie can send her

And the iron boats go as the mariners all know

With the gales of November remembered

The dangers of these waters are ever present in the minds of the mariners who sail them aboard the iron boats hauling taconite and other materials between ports on the lakes. There is reverence for those who have died and respect for the immense power of the water and the weather in combination in this area. This respected is further focused on the area where the Edmund Fitzgerald went down as 240 of the 300 shipwrecks occurring on the Great Lakes have occurred in the area near Whitefish Point.

In a musty old hall in Detroit they pray

In The Maritime Sailor’s Cathedral

The church bell chimed, ‘til it rang 29 times

For each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald

Although Lightfoot refers to “The Maritime Sailor’s Cathedral”, this is simply poetic license to describe the “Mariner’s Church of Detroit”. This church operates under the Episcopal Diocese of Michigan. The church was established in 1842 and for a time during the Civil War was a stop on the Underground Railroad which transported fleeing slaves to freedom in Canada. The church is a limestone structure equipped with a bell tower. Each spring the church blesses the fleet as they began operations on the Great Lakes. In November of 1975, upon hearing of the loss of the Edmund Fitzgerald and its crew, the church bell housed in the bell tower was rang 29 times as an acknowledgement of the 29 lives lost on board the vessel.

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake they call Gitche Gumee

Superior, they said, never gives up her dead

When the gales of November come early

True to the long living Indian legends regarding the lakes, most of those who die there remain there in the deep, dark waters. For the first time in the song, Lightfoot also acknowledges the tie between Lake Superior and the name Gitche Gumee. The Edmund Fitzgerald is of but one example of the many mariners and others who have perished in the icy waters when the storm season arrives without warning.

The Edmund Fitzgerald Crew:

Armagost, Michael E., age 37, Iron River, Wisconsin serving as Third Mate.

Beetcher, Fred J., age 56, Superior, Wisconsin, serving as Porter.

Bentsen, Thomas D., age 23, St. Joseph, Wisconsin, serving as Oiler.

Bindon, Edward F., age 47, Fairport Harbor, Ohio, serving as 1st Assist. Engineer.

Borgeson, Thomas D., age 41, Duluth, Minnesota, serving as Maintenance Man.

Champeau, Oliver J., age 41, Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, serving as 1st Asst Engineer.

Church, Nolan S., age 55, Silver Bay, Minnesota, serving as Porter.

Cundy, Ransom E., age 53, Superior, Wisconsin, serving as Watchman.

Edwards, Thomas E., age 50, Oregon, Ohio, serving as 2nd Asst. Engineer.

Haskell, Russell G., age 40, Millbury, Ohio, serving as 2nd Asst. Engineer.

Holl, George J., age 60, Cabot, Pennsylvania, serving as Chief Engineer.

Hudson, Bruce L., age 22, North Olmsted, Ohio, serving as Deck Hand.

Kalmon, Allen G., age 43, Washburn, Wisconsin, serving as 2nd Cook.

MacLellan, Gordon F., age 30, Clearwater, Florida, service as Wiper.

Mazes, Joseph W., age 59, Ashland, Wisconsin, serving as Special Maint. Man.

McCarthy, John H., age 62, Bay Village, Ohio, serving as First Mate.

McSorley, Ernest M., age 63, Toledo, Ohio, serving as Captain.

O’Brien, Eugene W., age 50, Toledo, Ohio, serving as Wheelsman.

Peckol, Karl A., age 20, Ashtabula, Ohio, serving as Watchman.

Poviach, John J., age 59, Bradenton, Florida, serving as Wheelsman.

Pratt, James A., age 44, Lakewood, Ohio, serving as 2nd Mate.

Rafferty, Robert C., age 62, Toledo, Ohio, serving as Steward.

Riippa, Paul M., age 22, Ashtabula, Ohio, serving as Deck Hand.

Simmons, John D., age 62, Ashland, Wisconsin, serving as Wheelsman.

Spengler, William J., age 59, Toledo, Ohio, serving as Watchman.

Thomas, Mark A., age 21, Richmond Heights, Ohio, serving as Deck Hand.

Walton, Ralph G., age 58, Fremont, Ohio, serving as Oiler.

Weiss, David E., age 22, Agoura, California, serving as MarinerAcademy Cadet.

Wilhelm, Blaine H., age 52, Moquah, Wisconsin, serving as Oiler.

©Copyright WBrown2010. All Rights Reserved.