The Age of American Unreason: A Book Review: Part Two

The Review Itself

We might as well get right into it. As I said in part one, to a certain extent Jacoby provides us with a "Good Old Days" thesis. In general, such a proposition has it that society functioned much better, once upon a time, in one way or another; and between those halcyon days and our own, current, fallen times, there has been a substantial qualitative drop off of the level of that functioning, whatever it may be.

Does that make sense? The Good Old Days thesis implicitly asks what went wrong.

I also suggested in part one, that a good way to engage a Good Old Days thesis is to ask if the Good Old Days were really, indeed so "good."

In the Good Old Days...

Susan Jacoby writes: "The unwillingness to give a hearing to contradictory viewpoints or to imagine that one might learn anything from an ideological or cultural opponent, represents a departure from the best side of American popular and elite intellectual traditions. Throughout the last quarter of the nineteenth century, millions of Americans---many of them devoutly religious---packed lecture halls around the country to hear Robert Green Ingersoll, known as 'the Great Agnostic,' excoriate conventional religion and any involvement between church and state. When Thomas Henry Huxley, the British naturalist and preeminent popularize of Darwin's theory of evolution, made his first trip to the United States in 1876, he spoke to standing-room-only crowds even though many members of his audiences were genuinely shocked by his views on the descent of man. Americans in the 1800s, regardless of their level of formal education, wanted to make up their own minds about what men like Ingersoll and Huxley had to say. That kind of curiosity, which demands firsthand evidence of whether the devil really has horns, is essential to the intellectual and political health of any society. In today's America, intellectuals and nonintellectuals alike, whether on the left or right, tend to tune out any voice that is not an echo. This obduracy is both a manifestation of mental laziness and the essence of anti-intellectualism" (1).

Remember, what we're trying to do is ask the question: How good, really, were the good old days? In order to try to answer that question, we need to try to integrate all that we know to have been going on at the time.

In other words, yes, during the last quarter of the nineteenth century people were packing lecture halls to hear Thomas Henry Huxley's views on the "descent of man." And he spoke to standing room only audiences, even though many of them were "genuinely shocked" by his ideas. Nevertheless, they had to see for themselves whether or not "the devil really has horns," and all that.

I'm going propose something. I will admit, from the outset, that I may be reaching by quite a bit, but I'll say it anyway. The historian Nell Irvin Painter wrote an intellectual history of the development of scientific racism in the United States called The History of White People. From that book she gives us the term polygenesis.

Polygenesis is the idea that different colored human beings (or "races") arose from separate acts of divine creation. "This view, soon known as polygenesis," writes Dr. Painter, "traced humanity to more than one origin of Genesis. Polygenesis went on to flourish in the mid-nineteenth century among racists of the American school of anthropology. While the publication of The Origin of Species in 1859 much reduced the allure of creationism of all kinds, Darwinism did not kill off polygenetic thinking entirely" (2).

Dr. Painter goes on to say that obstetrician Charles White "correlated economic development with physical attractiveness, joining the lengthening lineage of those who considered the leisured white European not only the most advanced segment of humanity but also 'the most beautiful of the human race.' To close his Account of the Regular Gradation in Man, White poses a series of rhetorical questions focused on two persistent themes of racial discourse: intelligence and beauty" (3).

Focusing on the audiences for Thomas Henry Huxley's lectures on Darwinian evolution, if you put those two things together (seemingly fair-minded attention by people who were "genuinely shocked" and the existence of the doctrine of polygenesis), what do you get?

Well, let us consider the doctrine of polygenesis and what a conservatively religious, racist white supremacist might do with it. Polygenesis, if you think about it, might have constituted a way of dis-relating humanity, making them separate. It might have constituted a way of conservatively religious, racist white supremacists of saying something like: Okay, evolution for you people, divine creation for us. Pristine, clean Godly manifestation for us and crawling out of the mud-ball evolution for you.

Let's say something like that. In which case, many of the people packing the lecture halls to hear Thomas Henry Huxley might have been attending with the same curiosity that you and I might attend a lecture on the mating habits of the humpback whale.

Do you follow me? If I am right, this tells us something about what white Americans were getting out of a culture of intellectualism in "the good old days." I call it the subliminal narcotic of white supremacy ego gratification.

When that narcotic was withdrawn, or could not be supplied any longer, Americans lost interest in intellectualism. I will develop this line of argument more thoroughly later on. We're just getting warmed up. I only quoted that Susan Jacoby passage from the introduction of her book.

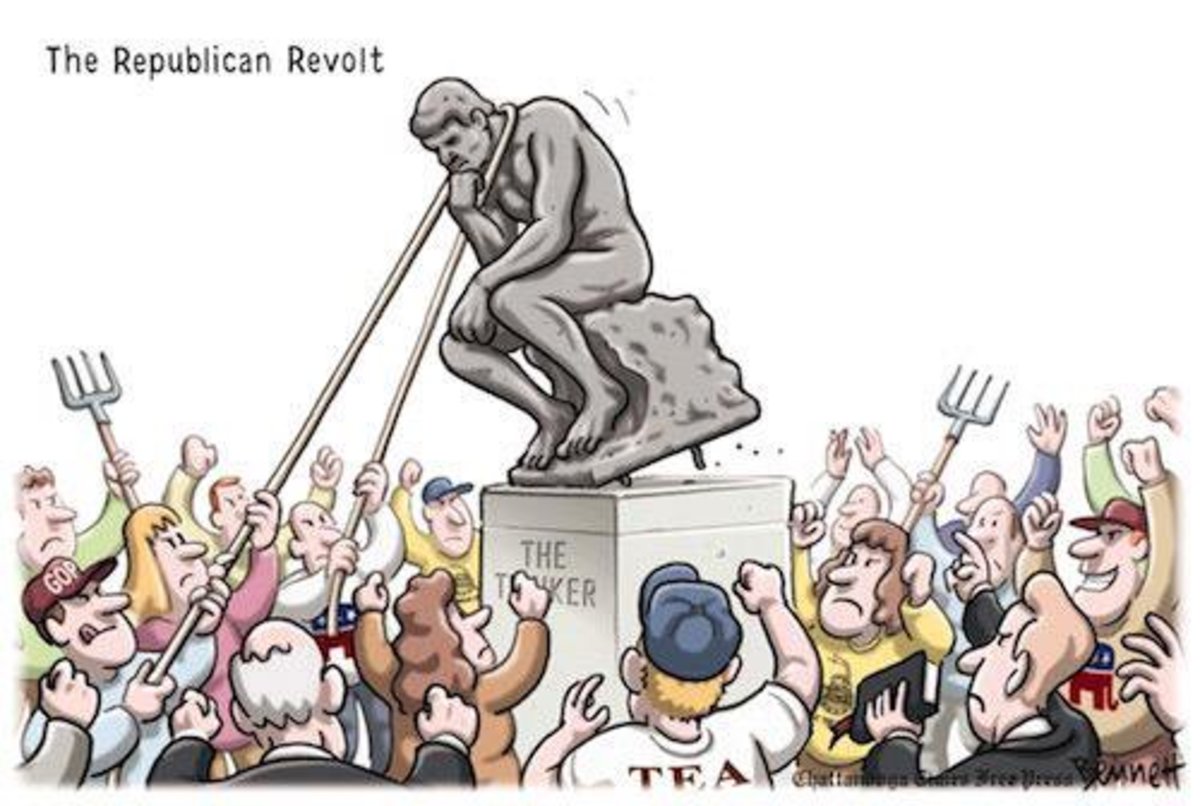

Let's look at something else. Two words that Jacoby uses to describe the current American cultural condition are anti-rationalism and anti-intellectualism. Here's what she has to say about anti-intellectualism (I'm not giving a definition here).

Anyhow, she writes: "Anti-intellectualism in any era can best be understood as a complex of symptoms with multiple causes, and the persistence of symptoms over time possesses the potential to turn a treatable, livable condition into a morbid disease affecting the entire body politic. It is certainly easy to point to a wide variety of causes---some old and some new---for the resurgent American anti-intellectualism of the past twenty years" (4).

Get ready! Susan Jacoby is about to go into some of the "causes" for the "resurgent American anti-intellectualism of the past twenty years."

Jacoby writes: "First and foremost among the vectors of anti-intellectualism are the mass media. On the surface, today's media seem to offer consumers an unprecedented variety of choices---television programs on hundreds of channels; movies; video games' music; and the Internet versions of those products, available in so many portable electronic packages that it is entirely possible to go through an entire day without being deprived for a second of commercial entertainment" (5).

She continues: "And it should not be forgotten that all of the video entertainment is accompanied by a soundtrack, usually in the form of ear-shattering music and special effects that would obviate concentration and reflection even in the absence of visual images. Leaving aside the question of whether it is a good thing to be entertained twenty-four hours a day, the variety of entertainment, given that all of the media outlets and programming divisions are controlled by a few major corporations, is largely an illusion.

"But the absence of genuine choice is a relatively minor factor in the relationship between the mass media and the decline of intellectual life in America. It is not that television, or any of its successors in the world of video, was designed as an enemy of active intellectual endeavor but that the media, while they may not actually be the message, inevitably reshape content to fit a form that subordinates both the spoken and the written word to visual images. In doing so, the media restrict their audience's intellectual parameters not only by providing information in a highly condensed form but by filling time---a huge amount of time---that used to be occupied by engagement with the written word" (6).

There we are! We have found what we were looking for. In that passage above, you can see that Susan Jacoby has identified, as a "cause" of the "resurgent American anti-intellectualism of the past years," the "mass media," which is guilty of "restrict[ing] their audience's intellectual parameters not only by providing information in a highly condensed form but by filling time---a huge amount of time---that used to be occupied by engagement with the written word."

I don't mean to nitpick, believe me. But is the mass media (and its deleterious effects) a cause or effect of anti-intellectualism? Suppose we pose a question like this: Would a society that had remained devoted to intellectualism have allowed the mass media to become parasitical on their "engagement with the written word"?

Or put another way: Would a society that had remained devoted to intellectualism have supported a mass media that was trending to parasitism on their "engagement with the written word"?

This question is especially relevant given the fact that, in the fifties, "many intellectuals had great hopes for television as an educational medium and as a general force for good. Television coverage had, after all, spelled the beginning of the end for Senator Joseph R. McCarthy in the spring of 1954, when ABC devoted 188 hours of broadcast time to live coverage of the Army-McCarthy Hearings. Seeing and hearing McCarthy , who came across as a petty thug, turned the tide, turned the tide of public opinion against abuses of power that had not seemed nearly as abusive when reported by the print media" (7).

I think the answer is that something, some X-factor---as we shall call it for now---caused American society, as a whole, to turn away from intellectualism, and the mutation of mass media, which "restrict their audience's intellectual parameters not only by providing information in a highly condensed form," which cuts into time "that used to be engaged with the written word," stepped in to fill the void, as it were.

Just what that X-factor is will be the subject under investigation in this series of essays in review of The Age of American Unreason.

Thank you for reading. See you in part three.

References

1. Jacoby, Susan. The Age of American Unreason. Pantheon Books, 2008. xix-xx

2. Painter, Nell Irvin. The History of White People. W.W. Norton & Company, 2010. 70

3. ibid

4. Jacoby, S. 10

5. ibid, 10-11

6. ibid, 11

7. ibid, 11