The Birth of the Modern: World Society 1815-1830 Review

It is an ambitious task to attempt a history of the entire world, and perhaps even more so when it covers a time period of 15 years. But if there happens to be a book which might attempt to fill such a divide, the impressively hefty and thick The Birth of the Modern: World Society 1815-1830 might be the one to do it, with exactly a thousand pages. But of course, even more than just laying out the history of the period there is the attempt to make the author's point - that 1815-1830 was the birth of the modern bourgeois, technological, democratic, mass society world order, which constitutes the modern era, rather than say, 1776, the industrial revolution revolution's coming of age in the 1780s, or 1789. His story is one which principally focuses on what he views as the progenitor of the modern age, Britain, recounting its story with the airy confidence that anything from Britain would later spread out elsewhere.

Content

The first chapter, devoted to the special relationship, is in effect a history the intricate affair of the War of 1812, and its corollary, American expansionism. For the author, this represents the birth, the foundation, of the elements which would lead to the "special relationship", between the US and the UK, tying together the two greatest English speaking nations in a special friendship, based upon a treaty that was far sighted in changing nothing, and thus leaving a peace without victors nor vanquished. So too, the first stirrings of a cultural and political admiration and entente between the two sides began to take shape.

In the second chapter, devoted to the congress of Europe, perhaps the reason for why the author is so determined upon the belief that the modern world was born in 1815 rather than early, be it 1776, or the 1780s, or 1789, is placed: a great loathing for Napoleon, and a depiction of a magnanimous and ultimately far sighted peace conference that managed to set together a stage for a lasting European peace, a depiction mixed with intricate depictions of the characters involved and the final contortions of the Napoleonic era in the years leading to 1815 and the crimes of the French emperor himself. But most of the chapter is devoted to the cultural developments in Europe, above all else in France, Britain, Germany, and Italy, during this period - the changing role of the artist, music, the opera, painting, the influence of Romanticism and some of its literature, and the sparkling away of new arts and presentations that emerged to cater to a large, middle class public.

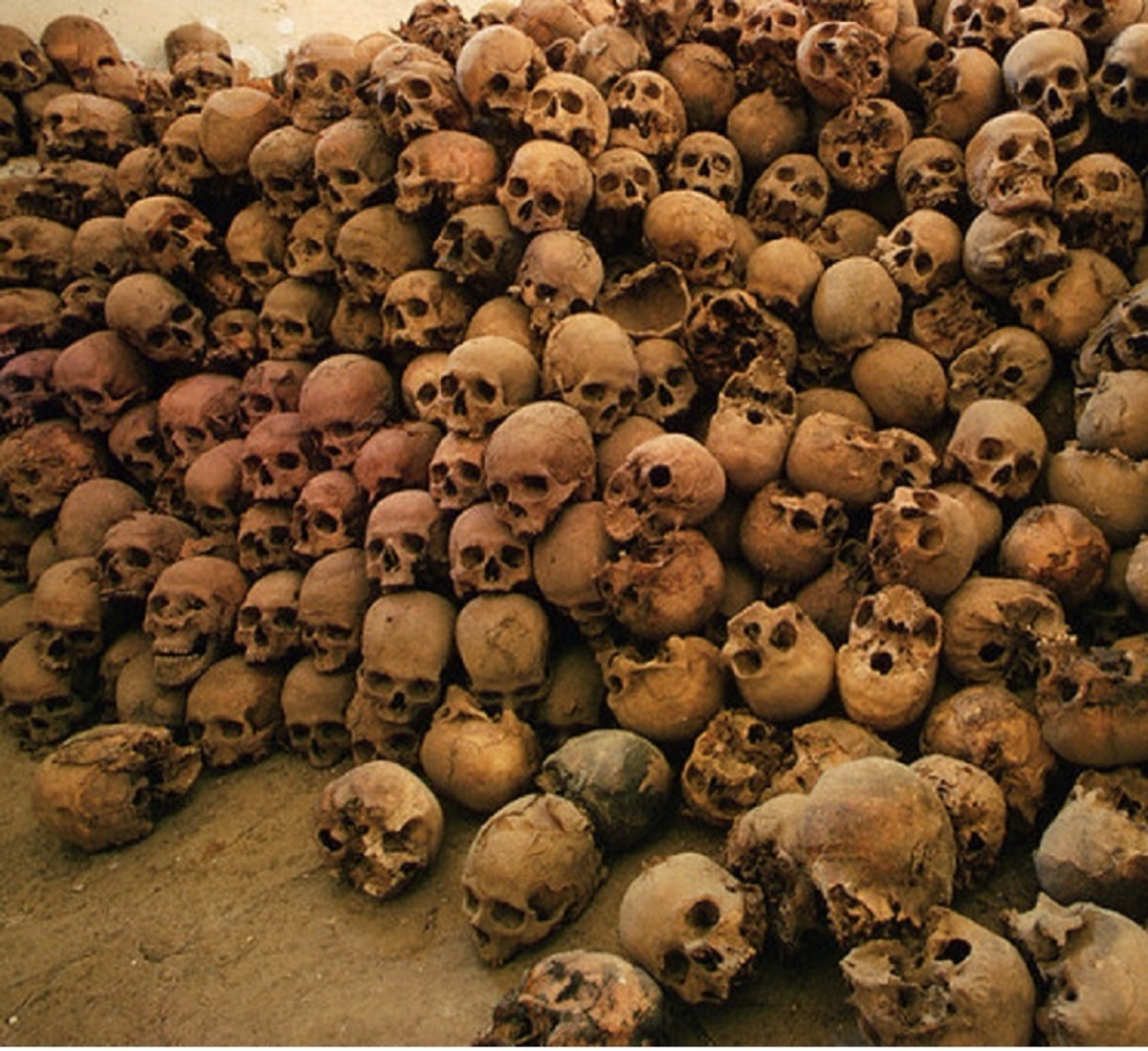

The End of the Wilderness constitutes a third chapter, dedicated to the immense transformations of transportation technology and the movements of people, partially as a result. Even if the steam engine was just beginning to enter its heyday, the British road and communication system improved dramatically. The postage system in Britain and abroad also became more and more effective. Meanwhile, with the huge population boom in Europe and at the same time the improving nature of transportation technology, led to a huge outflux of European settlers around the world. The dynamics of this settlement and the annihilation of the natives, be it in the expanding Russian Empire, America and Australia (which take up the lion share of the chapter), or Argentina and South Africa, represent a key part of the chapter. This destruction of the wilderness around the world was mourned by some, and perhaps in part created the reason for the boom for gardening.

World Policeman principally devotes itself to the subject of slavery, serfdom, and the campaign to suppress the slave trade and make the world safe for legitimate commerce, something that the British took the leading role in. In this, it goes across to the world to the various interventions of the Royal Navy, starting with the bombardment of Algiers in 1816, along with serfdom and the utopian military colonies in Russia, slavery in the United States, and the Royal Navy's suppression of the slave trade and its founding of colonies such as Singapore and anti-piracy activities in the Far East.

Can the Center Hold? deals with the maintenance of political order and political life in the United Kingdom, focusing on why the British did not succumb to a revolution like across the channel in France, religion in the UK, and political norms and manners in British elections and politics. Intellectuals such as poets and writers were intricately bound up in this and are discussed as well. Ultimately the forces of revolution were constrained, sometimes through military measures as Peterloo indicates, although the author seems to take a rather favorable view of this.

However, if the British avoided revolution, the regent and later king, George IV, was deeply loathed, as is related in "Honorable Gentlemen and Weaker Vessels", another chapter devoted almost entirely to the United Kingdom and upon the relationships of intellectuals to politics and some of their key members, marriage, relations between the sexes, the role of women, changes in women's status and perceptions of their status, and the affair of Queen Caroline who tried to return to the United Kingdom and was faced with divorce by her husband, the king.

This is followed by another chapter which principally is devoted to intellectual, scientific, and artistic advances, "Forces, Machines, Visions." Once again an almost entirely British focused chapter, this one deals with some of the technological advances of the era, starting with the safety lamp in mines, alongside some of the impressive theoretical advances and some of the failures, such as Babbage's Analytical Engine. It then proceeds onto painting and aesthetics, in an era where the author proclaims London as the center of many new international standards for the arts.

Returning to abroad, in a book which is supposedly about "World Society" after all, is Masques of Anarchy. This commences with the bloody wars which saw the collapse of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, before proceeding onto the instability in Spain itself, and the simmering, low level organizations of various liberal dissidents in Italy, famously enmeshed with Lord Byron. It concludes with another revolution, one which actually came to pass this time in stark contrast to Italy, the Greek War of Independence against the Ottomans, a sordid affair according to the author and nearly suppressed by the Ottoman and Egyptian (under the leadership of an oriental despotism of Muhammad Ali, not to be confused with the later boxer), where a joint Franco-British-Russian peace keeping intervention saved the rebels.

Fresh Air and Drowsy Syrups reflects upon the spread of mass sport, before moving onto childhood, education (where an astonishing number of figures were self-educated or educated at home), child prodigies, medicine, nutrition, drink, and drugs. In this, it includes an extensive piece about European involvement with China, where the British began to increasingly sell opium to the Chinese - the author also using this as a place to position his description (extremely negative) of the country and a defense of European morality in dealings with it.

Enormous Shadows opens with the spread of European imperialism and control throughout Southeast Asia, before looking at the ideologies that began to be formed in Japan - a shinto revivalism that later fostered an ultranationalist militarism - and Germany, with the world-spirit and legitimization of later aggression and dominance. But there were important other ideas, like the Saint-Simonisme from France which was the first modern industrial development philosophy, and which played a crucial role in Marxism, and the development of archaeology. These had an important influence in another country as well, Russia, which constitutes a lengthy part of the chapter, dealing with its political developments and above all else the Decembrist revolt and its aftermath in 1825.

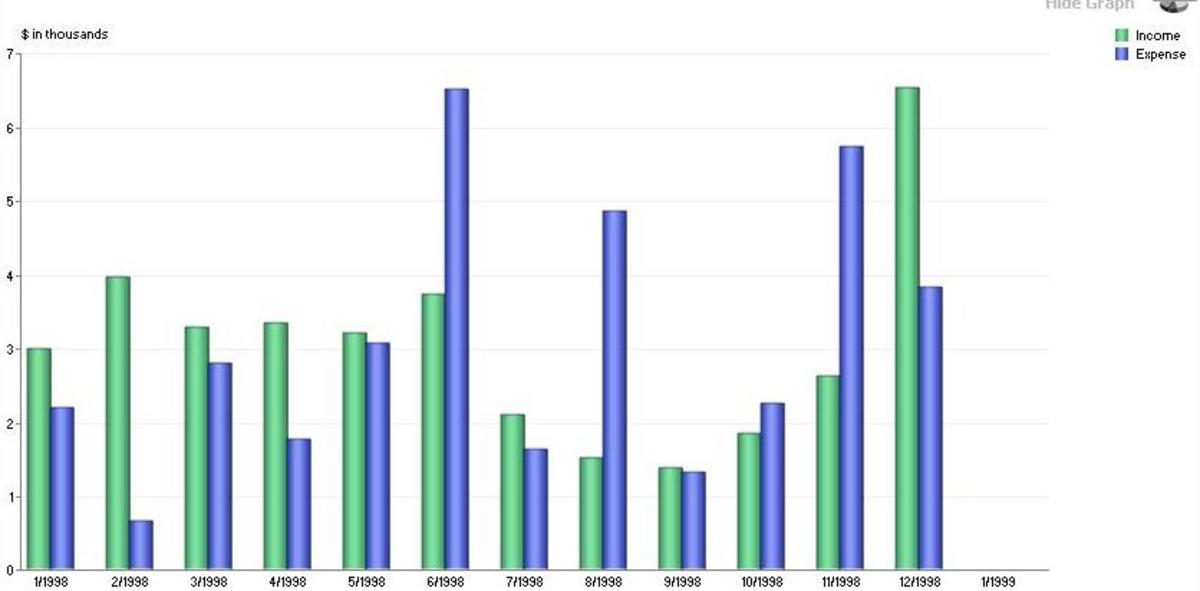

Crash! deals with the economic expansion and subsequent economic depression, from the 1819 American economic crisis to the 1826 economic downturn. This is principally reflected in Britain and to a lesser extent France (where it covers the printing trade in depth), showing the changes that were produced too in new technology that eased household life, at least for the rich, the legalization of unions and problems associated with this, and criminality reforms. South America's independence led to huge loans being taken out by the new countries, which cost them dearly when the world's first economic crisis hit in 1826, a devastating affair in much of Europe that led to much damage.

Demos is related to the march of democracy, starting with the United States and the election of Andrew Johnson. It also dealt with its British equivalent, in a populist Irish movement which was important in providing for Catholic emancipation, and the French 1830 revolution, as well as uprisings in Poland and Belgium. Democracy was on the march in some form, even if slowly and oft lacking in a popular element.

It might be I suppose, a controversial style of writing, to flick from one subject to another and to tie together things as wide ranging from child prodigies and education with the British selling of opium in China, but this in essence, might perhaps be to me part of what is the great strength of this book. A thousand pages is a lengthy expanse of canvas upon which to paint one's story, but even with this, one can be stunned sometimes by Paul Johnson's sheer degree of knowledge about some affairs, above all else in England, where he can recount almost byzantine descriptions of English art, poetry, literature, and mass culture inventions, and sometimes other societies can even dare to receive some degree of attention on such a scale as well, such as Russian prisons and Decembrist plotters or some French cultural agents.

This writing too, responds to what I come to think of as perhaps a characteristically British historical writing trait: an extensive and extremely passionate focus on characters. For myself, admiring the way that the book is written, the hefty lists of anecdotes (consider for example, the amusing recounting of the assassination attempt on the British War Minister Palmerston, where he was grazed by a bullet but then proceeded to work the entire day and only saw a doctor in the evening, with the only advice being to eat a diet without meat - and following this, that he later approved a letter written by the would-be assassin asking for his re-installment in the army!), the extensive character descriptions which form more than simple blurbs but avoid the tediousness of full bibliographies (consider here the story of King George IV, Lord Byron, or Andrew Jackson), and the plentiful reports on particular events which present them on a human scale, be it the attacks on Burma or South American revolutions, makes a thousand pages read quickly and without the woe that such a lengthy text could otherwise instill. A polished and excellent vocabulary joins it, producing a book which as far as literary talents go, is fully worth its time. It is the product of a popular historian, and in many ways its biases show (trade unionism for example), as well as that it is reflecting the interests of the author rather than responding to a simple pure historical method, but it is eminently readable stuff and the depth of knowledge overcomes many deficits.

But there is a critical failing for the book too, and that the very title of the volume is in of itself, a blatant lie. The claim of "World Society", is made into a mockery into this volume, which is in no sense a history of world society: it is the triumphal recounting, in splendid detail admittedly, of British society, occasionally joined by other powers but fundamentally centered on the United Kingdom. It does recount some of the cruelties exercised by this empire, such as its brutal destruction and crushing of native peoples around the world - although here it is careful to note that it was hardly alone, and to stress the advantages which it netted Europe as a whole - but ts depiction of the United Kingdom itself is positively rosy, a land of great social progress, mobility, intellectual sophistication, advancement, and with decent, good, honorable institutions. Perhaps it is nostalgia, but it also serves as a way of rehabilitating the general history of the British Empire, by painting as many positive elements and ignoring the negative ones. And above all else, it is based on the idea that Britain represented all that was inevitable about modernity, that it sufficed merely to recount how Britain was to then adumbrate how the rest of the world would inevitably develop. Thus there is little need to examine overmuch how politics, business, culture, and science worked in most of the world, other than the occasional fig leaf of an examination in France or the United States (itself portrayed as a faithful follower of the British model, bound to reconciliation with it over time), or Russia, because Britain was modernity, and hence the birth of the modern and what would become world society could simply be summed up by talking about it alone and some other empires to provide occasional context for its action.

So too, this similarly apologetic take is done overseas. Most non-European societies receive extremely little attention: the sole one which does is China, painting a thoroughly dismal view of the Middle Kingdom, riddled by corruption, myopia (for instance the thoroughly bizarre proclamation that Chinese economic theory was illogical because it viewed the exodus of silver or people from the state as a weakness, when almost all European nations took this same exact view, including the British themselves to some extent), and rebellion - and one which includes some things which must have been long since discussed at the time of the writing of the book in 1991, such as that the reason why the Chinese did not buy British goods was no mystery, but rather that there was no need for them, the Chinese already having a manufacturing base which produced any goods that they needed with sufficient quality and price that there was no need for imports of things such as textiles. Adam Smith himself had written upon the topic, so to remain in ignorance of this is willful. The intent with this portrayal of China (one which lacks in nuance and fails to provide for example, discussion of how Western views of China changed to become such a negative picture after a lofty and admiring look from Voltaire) is above all else to provide some sheen of legitimacy for the British sale of opium against China. Chapters like this, full of material which having studied the subject, know to be wrong, raise suspicions about other elements: just how accurate is say, his highly negative view of South American independence?

Paul Johnson would have been far better off if he had simple entitled this "Britannique and the Birth of the Modern: 1815-1830".The book which he produced in the end is one which opens up with a valiant attempts at internationalism, before then ultimately simply slipping back to the UK, and from then on out little budging except to document the woes and problems, the massacres and savagery, found in the rest of the world. Or more likely, it was never an accident at all: another book in a long trend of British writings which seek to place themselves at the center of the world experience and then find a way to justify it as a world or universal history. Paul Johnson may be a British conservative (which utterly defines his approach to the book and it should be taken as a perspective of what the old-style British conservative view of "world" history is), but his approach in this regard is the old story of Whig history, that the rest of the world is bound to one day be like Britain, evolving ultimately in the same manner and style to be functionally akin to it, and his book is another reiteration of the principle with an updated gloss upon it. In the end, I am myself not convinced that the author's view of 1815-1830 was the root of the modern age: rather it was the root of one particular aspect of it, the comfortable middle-class ascendancy bourgeois world order, which started in Britain it must be acknowledged, but which ignores the introduction to political, economic, and social modernity which was truly born in 1776-1789, and that even the wars which Johnson views as retarding this progress and being the last gasp of the era before the birth of his world order, are rather the reflection of the modern world being born.

In a certain sense, it is a book which is the history of an idea which in 1991, if the author knew it or not, was coming to an end - that of a world based upon the unquestioned dominance of Western power, defined by the position as first among equals or dominant powers within this system of the United States and the United Kingdom. Although the ranking of powers within might have changed, and although some of the ideas and elements without altered, it makes a curious irony that a book in 1991, at the very height of the last triumph of the West and the fall of the Soviet Union, stands in contrast to its disarray in 1815, one in which Europe had been torn to bloody ribbons by decades of rapacious and brutal war, and where an uncertain Russia lurked to the East, neither quite European nor not. Now, decades after the work of Paul Johnson, the cornerstones of what he saw as underlying the modern world are beginning to fall apart or fade, the luster decaying even while maintaining their old grandeur and significance externally. No longer can the modern world be viewed as simply the dynamic triumph of the English speaking peoples, first among equals in an expanding Western civilization focused upon Europe.

Paul Johnson's book is a history of a modern world, but the modern world that he wrote about is one which he penned at its last great heights. In this sense, despite its own valuable work, despite its richness, power, elegance in some parts, it is the history of an idea whose time, despite his own celebration of it, was at last coming to its end....

© 2019 Ryan Thomas