The Challenge of Journalistic Integrity and Ethics in The Face of Government Censorship

Intro

The study of journalistic ethics has been a popular debate over the years of reporting. Specifically, the unfiltered presentation of news to the public has been called into question, as it seems that stories about controversial government action seem too hindered and covered up. By examining both the PRSA Code of Ethics, and SPJ Code of Ethics it is evident that the chief goal of a journalist is to honestly portray the truth of matters to the masses. Both scenarios presented in this case study attempt to compromise that fundamental principle of journalism by filtering the truth. This hindrance of the public’s ability to hear the truth is not ethical in any respect. The government exists to serve the country and its citizens1, thus all citizens deserve to know the truth about what the government is doing.

Is it ethical to allow Censorship?

Scenario one calls into question whether it is ethical for a journalist to allow their work to be filtered or sanitized in order to preserve the affected party’s reputation. In this case, the affected party is the government, and the people would be receiving information that has been altered to hide truths. Ethically, a journalist should never submit or publish any work if they know that the people’s interest is not being protected. I consent that the harm done to either side must be considered, but the result of the government’s actions should never be harm to the public. Withholding information is indeed harm to the public because it results in the hindrance of the truth, and having the truth withheld from the public by the government is a loss of freedom to the public2. Through examination of both codes, it seems that, in regard to allowing journalists to preserve the integrity of public information, the SPJ is by far more ethical due to its preservation of public interest. It seems that the PRSA places too much emphasis on protecting confidential information and adhering to regulations. Whether the information is confidential or not, if it is harmful to the public it should be brought to light even if it results in imprisonment. The SPJ’s emphasis on Seeking truth, minimizing harm, and acting independently3 makes it the superior code of ethics, and leads to the conclusion that a reporter should not consent to the conditions for an exclusive interview given the imminent compromise of information that will ensue.

You can't outrun ethics!

A loss of Freedom

The chief role of government is to serve the people4, not to do them harm. Harm can be anything ranging from pain, death, loss of ability, or loss of freedom. In the first scenario, harm comes in the form of loss of freedom and hindrance of free expression “… about historical … political and moral questions…” 5 This harm is directed toward the public, by the government, in the form of incomplete truth. Even if the reporter in this scenario was to take the exclusive interview with the president, and gathered information about Guantanamo Bay, there is no way to guarantee that the truth would be told. The story would likely be filtered in a way that removes anything negative about the government, and would hinder the truth about historical, political, and moral questions that the public needs to know in order to develop a collective opinion3. The SJC states that “…public enlightenment is the forerunner of justice…” 6 and that an ethical journalist should “… strive to serve the public with thoroughness and honesty.” 7 It is in no way honest to knowingly allow the truth to be altered, and it certainly does not make publicenlightenment the forerunner of justice. The PRSA Code of Ethics states that “We are faithful to those we represent, while honoring our obligation to serve the public interest.” 8 In order to preserve free expression, it should always be the goal of a journalist to serve public interest because the public is in fact who we represent. This statement of loyalty in the PRSA Code of Conduct places public interest on the same level as loyalty to the represented party, when public interest should be the most important principle. Not only does this statement allow for altering the truth to protect the government, it allows the government to manufacture its own version of the truth. Due to the exceptional focus of the SPJ on preserving free expression at the risk of doing harm to the freedom of the public9, it seems to be the ethically superior code of conduct.

It's a mad scramble!

Participation in The Political Process

The secrecy of the government and their attempts to only allow positive stories regarding their actions prevents the people from obtaining the information that is necessary to participate in the political process10. Since the events revolving around September 11, the government has resorted to safeguarding information, citing that it would “compromise national security”11 However, in regards to the case presented in scenario one, in what way would it be a threat to national security to reveal truth to US citizens about the events occurring in Guantanamo Bay? The public could make their own decisions regarding the events, and by supporting their chosen officials, could move toward closing Guantanamo for good if they so choose. This kind of decision making process is what democracy is all about12. If the people are well informed, then they can make well informed decisions. From an ethical standpoint, I believe that the SPJ once again is superior to the PRSA in this regard. The SPJ states that ethical journalists should “Recognize a special obligation to ensure that the public’s business is conducted in the open a that government records are open to inspection.”13 This keeps the government accountable for their actions in that it calls for open inspection by the public. Accepting the interview under the circumstances given would violate the people’s right to inspect the records that the government keeps secret, and hinders their ability to make an informed decision. The PRSA requires that journalists “… maintain the integrity of relationships with the media, government officials, and the public.”14 Once again, the PRSA code puts government and the public on the same level, which is not ethical. The government works to serve the people through its interest in their wellbeing15. In regard to protecting the public’s right to be informed, and make informed decisions, the SPJ code is ethically more suiting than the PRSA Code.

An Informed Public

Ethics in journalism constantly mentions and alludes to the importance of keeping the public informed. This benefits society as a whole in that it allows the people to make informed decisions about the politics that, in many ways, have a major impact on their daily lives. This being the case, it is unethical for a journalist to withhold information that could benefit the public interest. The Espionage Act of 1917 has constantly been challenged as an infringement on the freedom of speech and press as mentioned in the First Amendment. Though, in most cases, the Supreme Court has ruled against the assertion that The Espionage Act violates the First Amendment, there is one very important exception: the case of New York Times Co. v. United States. I believe that scenario two bears many similarities to this case. There is no question that if one were to release this story, there would be a trial, but I believe there is justification enough to keep from going to prison. Even if a journalist were to go to prison over this scenario, ethically they would be responsible to do so according to the RTDNA Code of Ethics.

No Fear or Favor

Public interest does indeed demand publication of this report. The RTDNA Code of Ethics states that an ethical journalist should, “Gather and report news without fear or favor, and vigorously resist undue influence from any outside forces, including advertisers, sources, story subjects, powerful individuals, and special interest groups” 16 This means that no matter what circumstances are present, it is still necessary for the truth to be presented to the public. In this scenario, the public may need to know this information in order to choose the candidates that they are most suited for political office. Without the full representation of the truth, the public opinion of our elected officials and the effectiveness of our government are jeopardized. This being said, it is also necessary to try to investigate the truth of this story before publishing it. It is essential for an ethical journalist also to “Continuously seek the truth.” 17 Being ignorant to the possibility that the information received may be false is just as bad as withholding truth from the public.

The IPI

It seems to me that the IPI should publish this story as one article in itself. When Ellsberg leaked the story to the NY Times, he had to take it out of his safe volume by volume to be Xeroxed 18. In this circumstance, with the story being on a jump drive, the volume by volume method of publication is not necessary as the data could easily be uploaded at one time. If it were published under the IPI, it would come across as a deliberate attempt to inform the people for their own interest. It could not so easily be twisted to be seen as an attack on government or “… of such character that it is or might be useful to the enemy…”19 The IPI states in their preamble, “… a fundamental step towards understanding among peoples is to bring about understanding among the journalists of the world.”20 Publishing a work like this through the IPI is not only ethically correct, it is more prudent to do so in order to avoid allegations that one has violated something as serious as the Espionage Act of 1917.

Daniel Ellsberg

Poll on Government Censorship in Government

Is it ethical to allow the government to censor the news?

Confidential Sources

It would undoubtedly come up in a trial that you reveal your source of information. Ethically, a journalist should never reveal a source who has asked to remain confidential. The SPJ Code of Ethics states “... private people have a greater right to control information about themselves than do public officials …”21 Ethically, one should not give up a confidential source. It is up to the individual to decide whether or not to reveal their self. In the case of New York Times Co. v United States, the source (Ellsberg) did eventually give himself up and went on to serve a sentence in prison.22 Judging by what history shows and what journalism ethics tells us, it is not right to give up your source.

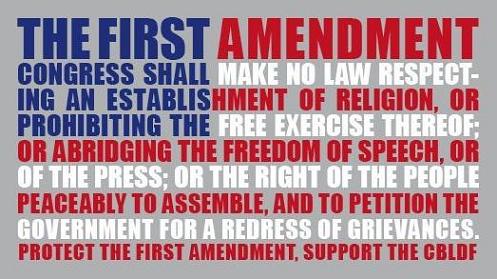

Expression of The First Amendment

To publish a story of this magnitude, one would definitely have to undergo a trial, especially under the Obama Administration, over the Espionage Act of 1917. The question becomes whether or not this is an expression of the First Amendment, and a use of the right to free speech, or an action against the US that puts National Security at risk. The First Amendment states: “Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press…”23 It seems that this situation is very similar to that of the case in which New York Times Co. won when facing the United States.24 Both situations involve an anonymous source, a controversial issue, and the question surrounding what freedom of press truly means. In the case over the Pentagon Papers, Justice Black states: “In my view, it is unfortunate that some of my Brethren are apparently willing to hold that the publication of news may sometimes be enjoined. Such a holding would make a shambles of the First Amendment.” 25 Shedding light on the events that occurred in Guantanamo Bay would serve to prevent torture of prisoners from happening in the future, as it is not an effective means of interrogation. This report in no way compromises the safety of US citizens, but works to prevent injustice from happening in the future and keeps the public informed. Having stated these things, I observe that a journalist could make their self well prepared before being prosecuted as an enemy of the state over this scenario.

The First Amendment

Conclusion

The foundation of ethical journalism is rooted in the pursuit of keeping the public informed of the true events that transpire within our country and around the world. This can be clearly seen by examining the RTDNA, PRSA, or SPJ Codes of Ethics. The government exists to serve the people, and journalism can be used to keep that true. I do recognize that there are some matters that the government must keep secret to protect its citizens, but there are many issues that the public is blind to because of government secrecy. These are things that need to be brought to light in order to ensure that the public is well informed politically, so that healthy democracy can continue. Scenario one presents a question about allowing the government to filter the truth, and whether or not certain journalistic codes are more ethical. Through my observation and research, it seems that government filtering of information is unethical and a journalist should never allow this to occur if possible. The SPJ Code of Ethics seems to be superior to that of the PRSA, in that it focuses more on public interest. Scenario two poses the question as to whether or not one should go to the extent of prosecution at the highest level to promote journalistic integrity and the wellbeing of public interest. Through observing the case of New York Times v. United States it seems that it is worth it, and that it can be done. Journalistic integrity and truthful portrayal of events should be pursued at any cost in order to keep the public educated, and to promote healthy government.

Sources

- Whitehead, John. "Thomas Jefferson: A True American Radical." The Rutherford Institute. The Rutherford Institute, 6 Apr. 2010. Web. 20 Apr. 2013. <https://www.rutherford.org/publications_resources/john_whiteheads_commentary/thomas_jefferson_a_true_american_radical>

-

2. Feinberg, Joel. "Meditating The Offense Principle." Offense To Others. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 1985. 44. Print.

3. Whitehead, op. cit. p.5.

4. Feinberg, op. cit. p. 44.

5. Feinberg, op. cit. p. 44.

6. "Society of Professional Journalists: SPJ Code of Ethics." Society of Professional Journalists. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2013. <http://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp>.

7. Ibid, p. 1. -

8. "Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) Member Code of Ethics | Statement of Professional Values | Code Provisions of Conduct." Public Relations Resources & PR Tools for Communications Professionals: Public Relations Society of America (PRSA). N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2013. < http://www.prsa.org/AboutPRSA/Ethics/CodeEnglish>

9. Feinberg, op. cit. p. 44.

10. Schulman, Miriam. "Ethical Challenges Facing Newspapers." Santa Clara University. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2013. < http://www.scu.edu/ethics/practicing/focusareas/media/newspaper.html >.

11. Ibid., p. 10.

12. Hutchings, Vincent. "Public Opinion and Democratic Accountability: How Citizens Learn about Politics." Princeton University Press. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2013. <press.princeton.edu/titles/7656.html>. -

13. SPJ, op. cit. , p. 1.

14. PRSA, op. cit. , p. 3.

15. Whitehead, op. cit. , p. 5.

16. "RTDNA Code of Ethics." RTDNA. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2013.

< http://rtdna.org/uploads/files/code%20of%20ethics.pdf >.

17. Ibid., p. 1.

18. COOPER, MICHAEL. "After 40 Years, the Complete Pentagon Papers - NYTimes.com." The New York Times - Breaking News, World News & Multimedia. N.p., 7 June 2011. Web. 20 Apr. 2013. <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/08/us/08pentagon.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0>.

19. "Espionage Act of 1917 legal definition of Espionage Act of 1917. Espionage Act of 1917 synonyms by the Free Online Law Dictionary.." Legal Dictionary. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2013.

< http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Espionage+Act+of+1917 >.

20. "Preamble." International Press Institute. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Apr. 1920. <www.freemedia.at/about-us/ipi-constitution.html>.

21. SPJ, op. cit. , p. 1.

22. Cooper, op. cit. , p. 21.

23. "Bill of Rights Transcript Text." National Archives and Records Administration. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2013.

< http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/bill_of_rights_transcript.html >.

24. "New York Times Co. v. United States."Legal Information Institute. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2013.

< http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0403_0713_ZC.html >.

25. Ibid., p. 1.