The Decades Between Wars: 20th Century American Literature

“To find a form that accommodates the mess, that is the task of the artist now.”

– Samuel Beckett

The American literature produced between World War I (WWI) and World War II (WWII) is characterized as an extension of modernism introduced by the fin de siècle and early-20th century writers (up to 1914); writers understood the United States in a base/superstructure relationship, and explored the role of the author as a microcosm living in a larger capitalistic universe. Thus, writers explored tensions in the superstructure such as “self-expression versus conformism, class struggle, sexuality and forbidden desires associated with the controversially of psychoanalysis, the double-consciousness of living as an African American, the repression of living as a woman, and the Otherness of not fitting into mainstream society” (Riederer, 2014). In other words, post-WWI Americans simply encountered new issues but felt the same concerns. Since these issues were so varied and diverse— affecting genders, races, nationalities, and cultures differently— a heteroglossic American consciousness was born, furthering fragmenting society. Thus, in the 1920s through the 1930s, a great number of new artistic trends developed in response to the outside stresses placed on the individual. Whether those stresses arose out of prohibition, industrialization, or the Great Depression— depending on the dialogic voice speaking— each trend bore its own burden of unique concerns related to the major political and social events that were transpiring.

The Lost Generation

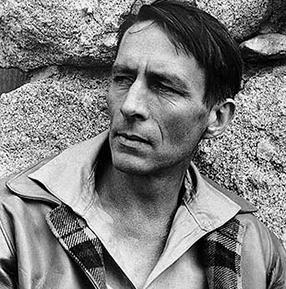

The Lost Generation writers, for instance, lamented the turmoil of WWI and languished for the future of the United States. These writers generally felt that the traditional values they were brought up with (Protestant, work ethic, conformism) were a sham, given the senselessness of the war and the consequent devaluation of human life (Murfin, Ray, pg. 240). Furthermore, many of these poets illustrated distaste for the capitalistic and industrial tendencies of American politics and economics. As a result, an artistic trend, primitivism, provided response to American modernity. Primitivists typically espouse a certain “back-to-nature” philosophy that has led to the glorification of both past eras and past cultures seen as “natural” in contrast to the largely urbanized and civil contemporary Western culture (Murfin, Ray, pg. 370). The American poet, Robinson Jeffers contemplates the natural and inevitable attrition of civilized, or technologized living in his “Shine, Perishing Republic.” Civilization, according to Jeffers is like a flower: it first bears fruit, then it begins to decay, and then it becomes part of the earth again. Living in human society is to be a part of the eternal cycle of nature: to constantly be born, reproduce, decay, and die over and again. His tone towards the argument of progress through technological advancement is skeptical at best, cynical at worst. Clearly Jeffers is at odds with the industrial and capitalistic trends of the Modern Period; thus his languishing exemplified through his Primitivist approach.

Expatriate Writers

Many American members of the Lost Generation became expatriates in the 1920s (Murfin, Ray, pg. 240). Some American writers were moving to France because, as Gertrude Stein said, Paris was “where the 20th century was” and because there they would have direct access to the artistic and literary ferment that was shaping the consciousness of the age (Fonner, Garraty, pg. pg. 371). But this exodus was, by no means, generalized as myth suggests. John Dos Passos was in and out of Paris as a visitor in these years, but his status was never that of an expatriate; nor was any sort of exile elected by Willa Cather, Wallace Stevens, William Faulkner, Marianne Moore, and numerous others; and even extended periods of residence abroad, as in the case of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway, often did not at all signal any slackening in commitment among these people to their native culture. But the great thing that was happening in the 1920s was an internationalization of the American writer’s sensibility (Fonner, Garraty, pg. 675). As myth has it, the period of the 1920s was the jazz age, the “gaudiest spree in history.” Yet in deep and important ways, American writers were entering into the full tide of modernist movement, submitting to its exacting disciplines of skepticism and technical experimentation.

Modernism

The modernist movement literally migrated from its origins in the cosmopolitan circles within Berlin, Vienna, Munich, Prague, Moscow, London, and Paris post-WWI moving into the United States by attaching to expatriate writers like fleas. These writers would, in turn, spread the various ideas of modernism through their literature and travels; and by the 1930s, modernist trends made their way into New York and Chicago. Thus, distance, travel, and location play an important role during the 20s and 30s for American authors by sparking a cultural diffusion of artistic trends (symbolism, impressionism, post-impressionism, futurism, constructivism, imagism, vorticism, expressionism, Dadaism, and surrealism); of course, these intellectual changes during the Modern Period may have never happened, or may have been slower to diffuse across international borders, if writers such as Jeffers, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald (among numerous others) did not travel abroad, live in other nations, experience foreign cultures, and embrace radical changes and new theories of art, politics, economics, justice and punishment, identity and society, religion, race, gender, technology, work and leisure, urbanization and industrialization, and language.

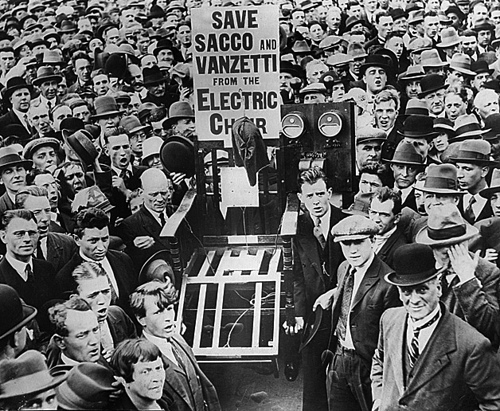

Sacco and Venzetti

This influx of foreign ideas and artistic trends often contradicted American values when some expatriate writers began returning home. For instance, the Sacco and Vanzetti case generated prolific responses tinged with foreign radicalism, and modernism that were at odds with American values. One such response by Edna St. Vincent Millay manifested in her verse in a poem titled “Justice Denied in Massachusetts.” Millay avoids directly referencing the Sacco and Vanzetti case in her poem; she does not mention anything about courthouses, judges, police officers, protesters, picket lines, electrocutions or anything of that such. Thus, she effectively naturalizes or depoliticizes the event: characteristic of Marxist poetry. Perhaps this aids to the feeling of languish she is stirring, even lamenting. Millay is clearly heartbroken and her grief is multifaceted; her spirit is broken (like the “broken hoe”) because: 1) Sacco and Vanzetti lost the case and were executed, 2) class differences fueled tensions throughout the trial, 3) political freedom in the U.S. seemed like a fluke after all, and 4) liberal movements seemed to be effectively halted for the time being (Riederer, Class Discussion). After all, the evidence Sacco and Vanzetti were found guilty upon were very shaky grounds: “consciousness of guilt” (Fonner, Garraty, pg. 961). This landmark decision put all radicals, liberals, and social-reform movements in danger of conviction, even if they were completely innocent.

The Great Depression

Continuing into the 1930s, amidst political, economic, and social uncertainty—perpetrated by several events: the Sacco and Vanzetti Case, the Great Depression, and FDR’s radical New Deal reforms for example—led to political rhetoric in American literature. The 1930s are most fruitfully characterized as a period during which many novelists were searching for alternative, noncanonical methods of intervening in the political realm (Solomon, pg. 815). Solomon argues, “Edward Dahlberg ironized the persuasive force of Marxist discourse [in his “From Flushing to Calvary”]; Tom Kromer ironized the epistemological or ontological authority of the realist novel [in his “Waiting for Nothing”]; and John Dos Passos undid the coercive and cognitive function of a particularly prominent trope [in his “The Body of an American”]” (Solomon, 1996). American poetry also developed a political rhetoric such as in E. E. Cummings’ “next to of course god america i,” which, according to Brian Docherty, “includes most of the clichés politicians mouth at election time, and his point is that while anyone who dared to criticized any of these concepts would be labeled un-American and a commie subversive, it is politicians like this who have muted the voice of liberty” (Docherty, 1995).

Concluding Thoughts

The idea of the Lost Generation writers was born post-WWI but its essence resonates throughout the entire 20th century; resurfacing during the 30s, post-WWII, and during the events of the Cold War. Even so, the Lost Generation writers represent only a single voice amongst the diverse and fragmented literature produced between WWI and WWII. While Americans experienced the same major political, economic events that transformed the American base, these events created drastically different responses in the superstructure. For instance, the Harlem Renaissance movement of African American writers had fundamentally different artistic and literary goals as the imagists, Dadaists, feminists, and impressionists. The Lost Generation writers and the expatriates captured the experience of living between wars, and more importantly, they more often than not grappled with all-important question: what does it mean to be American—distinctly American?

References

Docherty, B. (1995). On “next to of course god america i.” Retrieved from: http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/a_f/cummings/nexttoofcourse.htm

Foner, E., Garraty, J. (1991). The reader’s companion to american history. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Franklin et al. (2008). The norton anthology of american literature. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Murfin R., Ray S. (2003). The bedford glossary of critical and literary terms. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Solomon, W. (1996). Politics and rhetoric in the novel in the 1930s. American Literature (vol. 68). New York, NY: Duke University Press