- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- Literary Criticism & Theory

The Grimm Side of Fairytales

Introduction

Children’s literature during the Victorian era was characterised by three main genres. There were books which sought to emphasise and uphold the concept of gender roles in society, with domestic books like Little Women being targeted at girls, while boys were encouraged to read adventure stories such as The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. This period also witnessed the emergence of realistic stories such as Huckleberry Finn and The Little Princess, which explored social and controversial issues like wars, poverty, prejudice and racism. However, it was the revival of the fairy tale genre in the early nineteenth century that gained the most popularity amongst the Victorians, as it encompassed both entertaining elements and a strong presence of Christian doctrine.

The nineteenth century marked a shift in the adult’s attitude towards children’s fairy tales, triggering the remarkable contribution of fairy tale writers like the Brothers Grimm and Hans Andersen who started to pen stories that adapted to this change in perception. During the first two decades of the nineteenth century, many classical children fairy tales were being censored, since adults, particularly educators and church leaders, considered them to be inappropriate for a child’s educational development. As a result of this strict supervision on children’s literature, the Brothers Grimm started to remove the vulgar elements from their collection of fairy tales. Soon after, the middle-class became aware of the need to amuse children with fantasy stories and adults started to understand the important role that a children’s imagination played during their childhood years. The Grimm fairy tales fitted perfectly into this new perception of children’s literature as they had preserved the presence of wonder, fantasy and magic in their stories. Nevertheless, moral lessons and Victorian values were still embedded in the majority of the Grimms’ fairy tales, thus rendering them appealing to both children and adults. The Victorian concept of gender roles was also firmly entrenched in the Grimms’ fairy tales, particularly in tales like Cinderella, Rapunzel and Snow White whose plot revolves around a beautiful woman who falls victim to a cruel and evil entity.

The popularity of the fairy tale amongst the Victorians gathered momentum when Hans Andersen started publishing his own genre of fairy tales. Although Andersen attempted to eliminate stereotypical features associated with fairy tale characters and base the plots on his personal experiences, one of his most widely read tale, The Red Shoes, exhibits a strong sense of Christian teachings, Victorian morals, and possibly also a trace of the Protestant ethic. While most of Andersen’s tales delve into the character’s individuality and point of view, The Red Shoes digresses from such aspects, as the girl’s individuality and refusal to obey the adults’ instructions are severely punished.

Andersen’s The Red Shoes

While reading The Red Shoes, I identified a similarity between the structure of the story’s plot and that of the typical Tudor morality play. The latter was built on three fundamental concepts; temptation, transgression and repentance. Similar to the morality plays, The Red Shoes starts with the protagonist’s temptation, followed by a warning from another character and the protagonist’s final choice to transgress, and ends with an irrevocable punishment.

In her review of Andersen’s fairy tales, the critic Tess Lewis states that “Karen is punished for her vanity when she thinks only of her new shoes while taking communion.”[1] However, my interpretation of Karen’s sin and disobedience differs from Lewis’ observation. The red shoes possibly signify the material world which can take over one’s life if it is not controlled. The Christian belief that an obsession with material things separates one from God is strongly ingrained throughout the story. During mass, Karen is so transfixed by the splendor of her red shoes that she forgets to sing the psalms and say the Lord’s Prayer.

Despite the warning by the old lady, Karen leads herself into temptation by putting on the red shoes to go to the ball. This decision to be defiant and keep wearing the red shoes might signify Karen’s strive for independence, yet ironically, the red shoes will later make her dependent on them. The sin of surrendering oneself to the world of materialism is also highlighted in Karen’s speech after having ‘repented right heartily’ and promises the patronage that ‘she would be very industrious’ and would ‘not mind about the wages,’ and from then onwards she avoids speaking about ‘dress and grandeur and beauty.’[2] According to Jack Zipes, fairy tale writers from different European countries ‘emphasized the lessons to be learned in keeping with the principles of the Protestant ethic- industriousness, honesty, cleanliness, diligence, virtuousness.’[3]

Karen conforms to the principles of industriousness and virtuousness, but her effort in repenting does not save her from her untimely death.

Andersen’s choice of imagery in describing the angel is quite sinister, as if the writer’s aim is to instill fear in children by depicting a merciless angel. Ironically, the girl finds mercy from the local executioner, who saves her life by chopping off her feet. This image of Karen’s legs being amputated might be too graphic for children. The painful punishment does not even put an end to her suffering. Death is the ultimate punishment, but the way Anderson beautifully describes her soul ascending to heaven, ‘filled with peace and joy,’[4] her death can be interpreted by children as a reward for repenting.

The motif of the shoe appears in many other fairy tales, and it is usually attributed to a magical power, and in some particular cases, as in Andrew Lang’s The Twelve Dancing Princesses and the Grimms’ Cinderella, shoes are a token of freedom. The moment Cinderella’s foot fits perfectly into the golden shoe, she is freed from her life of slavery, yet as I shall point out in the following section, freedom for female protagonists is never the ultimate reward in fairy tales. The shoe in The Red Shoes symbolizes vanity and materialism as Karen is not satisfied with her ‘pretty and dainty’[5] looks and seeks to put on the red shoes to look better and impress. Gloria Fowler’s contemporary adaptation of The Red Shoes narrates the story from a different perspective, attaching a new meaning to the red shoes as they become a memory of Karen’s deceased mother. In Fowler’s story, Karen is forced to hand over her shoes to the princess, and that is when she realises that she doesn’t need the shoes to keep the memory of her mum alive.

[1] Tess Lewis, ‘A Drop of Bitterness: Andersen’s Fairy Tales’, in The Hudson Review, 54.4 (2002) <http://www.jstor.org.ejournals.um.edu.mt> [accessed 12 May 2011]

[2] Hans Christian Anderson, The Red Shoes in ‘Children and Youth in History’, <http://chnm.gmu.edu/cyh/primary-sources/203> [accessed May 12, 2011].

[3] Jack Zipes, ‘Towards a Definition of the Literary Fairy Tale,’ in The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales (USA: Oxford University Press, 2000), xxvii.

[4] Hans Christian Anderson, The Red Shoes in ‘Children and Youth in History’, <http://chnm.gmu.edu/cyh/primary-sources/203> [accessed May 12, 2011].

[5] Hans Christian Anderson, The Red Shoes in ‘Children and Youth in History’, <http://chnm.gmu.edu/cyh/primary-sources/203> [accessed May 12, 2011].

The Brothers Grimms’ Cinderella

Karen’s defiant nature stands in contrast to Cinderella’s passivity, the protagonist of one of the most popularly read, retold and adapted tale by the Brothers Grimm. Unlike Karen, Cinderella submits to the orders imposed on her and wallows in self-pity. The fact that in the end she is rewarded with a happy marriage for her suffering reflects the Catholic belief that those who go through a great deal of suffering will be rewarded with the promise of heaven. Marcia K. Lieberman notes how ‘the girl who is singled out for rejection and bad treatment, and who submits to her lot, weeping but never running away, has a special compensatory destiny awaiting her.’[1] Yet it is also important to highlight the fact that this reward always involves a happy marriage. The one reward that Cinderella undoubtedly deserves is freedom, but she is spared from her older sisters’ cruel treatment and instantly submitted to the role of a dutiful and modest wife.

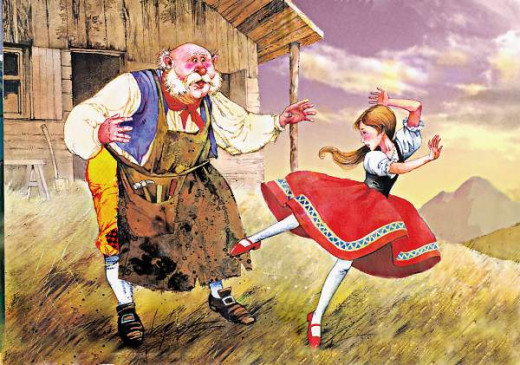

The conflict between good and evil underpins most of the plots in the Brothers Grimm tales. In an essay entitled On Fairy Tales and Moral Imagination, Vigen Guroian argues that ‘a well-fortified and story-enriched moral imagination helps children to move about in their expanding world with moral intent and ultimately with faith, hope, and charity.’[2] During the Victorian era, children were meant to familiarize themselves with the forces of evil in order to be able to identify any evil intent in real life. However, the interpretations of what constitutes an individual as being evil were quite misleading. Lieberman emphasizes the link between ugliness and evil that is foregrounded in the majority of fairy tales. This pattern is mostly present in fairy tales that involve the role of a cruel step-mother, who is usually paralleled to an evil witch, or the role of the nefarious step-sisters. In Cinderella, ‘good-temper and meekness are… associated with beauty, and ill-temper with ugliness.’[3] Lieberman goes on to say that this division leads to a sense of competition and jealousy amongst the female protagonists in the story, and eventually the fairest of them all is chosen by the prince. This fairy tale tradition of beauty and ugliness was also employed in the Disney adaptation of Cinderella. The animated film also conveys a stronger sense of envy and competition between the girls, an antagonistic attitude which can be easily duplicated in real life.

From the very beginning of the story, Cinderella is told by her mother to ‘continue good and pious, and Heaven will help you in every trouble.’[4] Throughout the story, Cinderella maintains this humbleness in hope of a reward for her suffering. Thus, as Guroian suggested, children are being taught to be faithful and hopeful and lead a moral life. Stories that followed a similar pattern to Cinderella’s plot were more appealing to girls than boys, so possibly the main purpose behind choosing such stories for middle and upper class girls over other more entertaining and adventure stories was to teach moral guidelines to female readers. These passive protagonists were portrayed as heroines, setting an example for girls who aspired to behave like princesses and be admired by those around them. For these reasons, feminist phenomenology ‘reveals Cinderella as a primer for moral and gender role conventions, leeched of race, gender and class.’[5]

[1] Marcia K. Lieberman, ‘Some Day My Prince Will Come,’ in College English, 34.3 (1972) <http://www.jstor.org/pss/375142>[accessed 12 May 2011].

[2] Vigen Guroian, ‘On Fairy Tales and Moral Imagination,’ in Catholic Education Resource Center <http://www.catholiceducation.org/articles/arts/al0130.html>[accessed 14 May 2011]

[3] Marcia K. Lieberman, ‘Some Day My Prince Will Come,’ in College English, 34.3 (1972) <http://www.jstor.org/pss/375142>[accessed 12 May 2011].

[4] Brothers Grimm, ‘Cinderella,’ in The Complete Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales (USA: Crown Publishers, 1981), p. 89.

[5] Rob Baum, ‘After the ball is over: bringing Cinderella home’ in Cultural Analysis <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_7072/is_1/ai_n28820063/> [accesses 14 May 2011].

Conclusion

Children’s books or stories published during a certain historical context tend to reflect the notion of childhood during that era. During the high peak of Romanticism, writers like William Blake mused over the nostalgic aspect of childhood and romanticized the innocence of children. However, the safeguarding of the child’s innocence did not last long, and as the Victorian era progressed, children were expected to cope with the atrocities of real life and the adult world. Things like theft, mutilation, sickness and death became a common sight for the Victorian child, thus the image of Karen’s legs being amputated was less likely to shock children reading The Red Shoes, whereas nowadays that image might be too morbid for children. In Cinderella, ‘the evil-minded and malicious sisters’ also receive a physical punishment which is as severe as Karen’s, for ‘the doves picked out the other eye of each, so they were for their wickedness and falsehood both punished with blindness during the rest of their lives.’[1] Perhaps they are not only punished for mistreating their sister, but also for their materialistic greed. In a Christian context, the dove symbolizes the Holy Spirit, therefore this disability inflicted on both sisters can be interpreted as a divine punishment.

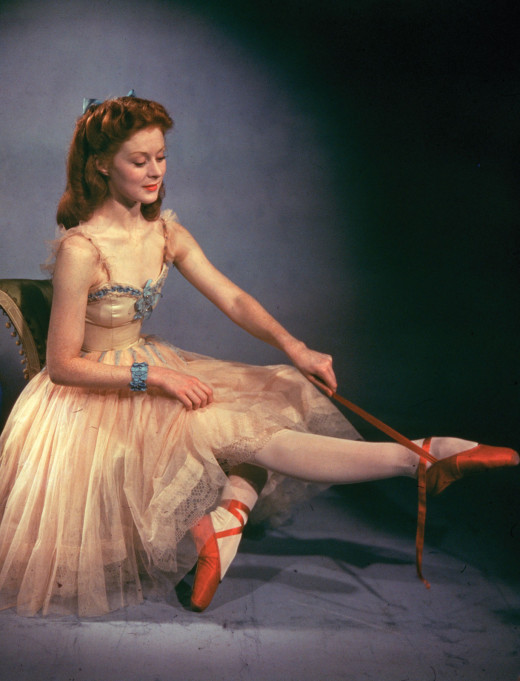

Nina. K Martin argues that ‘women have been consistently positioned in narratives as experiencing punishment for their desires,’ and illustrates how Andersen’s The Red Shoes is ‘a morality tale that pits piety and goodness against active female desires.’[2] Karen is indeed portrayed as the stereotypical Victorian girl who was ‘dressed very neatly and cleanly’ and ‘taught to read and to sew.’ Powell and Pressburger’s film The Red Shoes narrates a completely different story from Andersen’s tale, yet it puts across a similar concept. In this allegorical story about the obsession with art, Victoria Page, a flourishing ballet dancer, is torn between ordinary life and her unyielding passion for dancing. She is represented as a woman living in a patriarchal society, seeking independence and transgression. She chooses her career over marriage, yet she is driven to insanity by her choice and eventually commits suicide. This portrayal of a defiant and adamant female is also present in other children’s texts by Victorian writers. In Andrew Lang’s The Yellow Dwarf, the princess Bellissima is punished for refusing to marry any of her suitors. Lieberman argues that these fairy tale princesses are refusing marriage in order to ‘preserve their freedom and their identity.’[3]

Whereas The Red Shoes illustrates the serious consequences of a girl’s resistance to fulfilling her role as a pious and devout Christian, Cinderella can be interpreted as a girl’s guide to be ‘pious and gentle to all around her’[4] at all costs. Rob Baum carries out an accurate observation of the moral purpose behind Cinderella, suggesting that ‘Cinderella defines girls' first choice for a romantic partner, the strictures of friendship and obedience that girls are trained to uphold, unconditional family love and, not least, ideals of personal appearance and deportment.’[5]

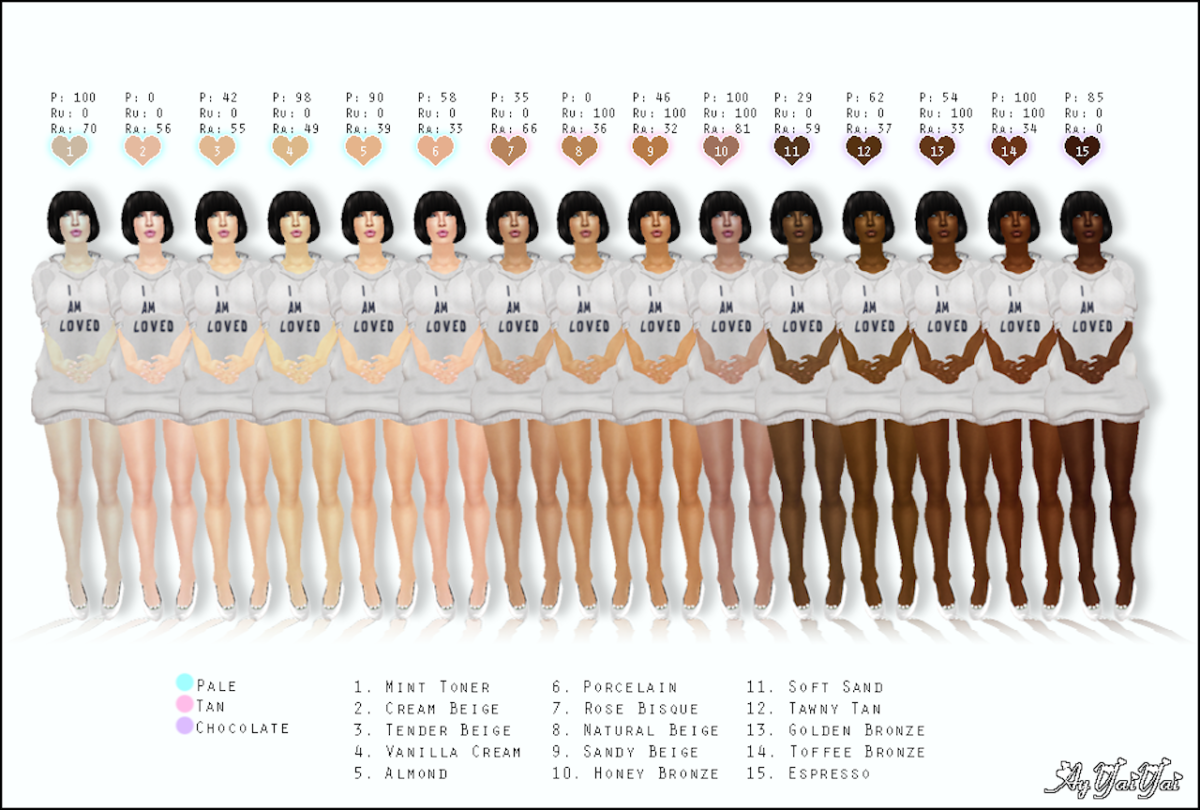

In a study about the female archetype in fairy tales, Lori Baker-Sperry and Liz Grauerholz rightly note that these fairy tales continue to be read ‘by children across various social class and racial groups, while continuing to contain symbolic imagery that legitimates existing race, class and gender systems.’[6] While this observation is quite true, nowadays many contemporary children’s books are challenging these stereotypical notions of gender and class. Consequently, children who read a variety of books are coming across different concepts about gender, family structures and race. Moreover, the gender stereotypes embedded in fairy tales do not mirror the established roles of both sexes in open-minded contemporary societies. These stories might therefore be considered as being outdated, yet some of the tales by the Brothers Grimm like Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, Snow White and The Little Red Riding Hood amongst other, remain favourite classics amongst young readers.

[1] Brothers Grimm, ‘Cinderella,’ in The Complete Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales (see above), p. 89-95.

[2] Nina K. Martin, ‘Red Shoe Diaries: Sexual Fantasy and the Construction of the (hetero)Sexual Woman,’ in Journal of Film and Video, 46.2 (1994) <http://www.jstor.org/pss/20688037>[accessed 12 May 2011].

[3] Marcia K. Lieberman, ‘Some Day My Prince Will Come,’ in College English, 34.3 (1972) <http://www.jstor.org/pss/375142>[accessed 12 May 2011].

[4] Brothers Grimm, ‘Cinderella,’ in The Complete Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales (USA: Crown Publishers, 1981), p. 89.

[5] Rob Baum, ‘After the ball is over: bringing Cinderella home’ in Cultural Analysis <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_7072/is_1/ai_n28820063/> [accesses 14 May 2011].

[6] Lori Baker-Sperry and Liz Grauerholz, ‘The Pervasiveness and Persistence of the Feminine Beauty Ideal in Children's Fairy Tales,’ in Gender & Society, 17.5 (2003) <http://www.jstor.org.ejournals.um.edu.mt/stable/3594706?seq=4> [accessed 14 May 2011].