The Inverted Eden

The Inverted Eden: Romantic Perspectives in Grizzly Man, Bear, and Equus

The return to Eden surfaces as a common motif in Werner Herzog’s film, Grizzly Man [1], Marian Engel’s Bear [2], and Peter Shaffer’s Equus. [3] In each of these texts, though, unlike biblical Eden, there is a blurring of the boundaries between human animal and nonhuman animal. This merging of human and nonhuman relates to a departure from a Christianity-based anthropocentrism, which departure is also seen in the Middle Ages. [4] In these texts, a variance from the traditional, biblical Eden is apparent, in that each of the protagonists (Timothy Treadwell, Lou, and Alan Strang, respectively) exhibits a communal relationship with his or her respective animals. The result is a romantic Eden, in which each of the characters either deifies nonhuman animals, or shares a fairer, closer-to-equal plane of existence with nonhuman animals. This romantic Eden opposes the classical forces that are present in the biblical Eden, in which human animals exhibit constant and absolute supremacy over nature and nonhuman animals.

In the garden of Eden, God grants human animals authority to rule over nonhuman animals (Gen 1:26), creating a clear boundary between the two categories of animals. However, Joyce E. Salisbury states that by the Middle Ages “the paradigm of separation of species was breaking down. It was harder to determine what defined an animal and what was definitively human.” (1) The Middle Ages was a time when some humans even made incantations to a deceased animal in hopes of divine protection for their children. [5] In this aspect the boundary between God and nonhuman animals was broken as the human/nonhuman animal boundary was broken. Likewise, in a twelfth century Latin bestiary, [6] nonhuman animals are used as symbols for God and for human animals, and are also paralleled and used interchangeably in themes of Christianity and proper human behavior–this is an example of an assimilatory text that possesses the blurring of this boundary between human and nonhuman animals. This symbolization of God with nonhuman animals solidified the breakdown of the human/nonhuman animal boundary, and aesthetic attributes of this diminished boundary have perpetuated to modern times, which can be observed in the three texts of Grizzly Man, Bear, and Equus.

Two specific perspectives follow in which one can approach the relationship between human animals and nonhuman animals: 1) either God has created definitive authority of human animals over nonhuman animals for a good reason, so that society can flourish and develop from resources provided by nonhuman animals; or 2) nonhuman animals should be revered and respected as being something not wholly dissimilar from human animals. John Rennie Short’s essay “Wilderness” [7] provides this dichotomy of perspectives by which nature (nonhuman animals included) is viewed. The classical perspective sees nature as something to be subdued and manipulated, and “sees most significance in human action and human society.” (6) The classical perspective is therefore associated with societal power structures, to include Christianity. Lynn White, Jr., in “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis” [8], posits that Christianity is linked to a dualism of man and nature, and “Christianity made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects.” (1205) Grizzly Man,Bear, and Equus all portray a removal of, or defiance against, these anthropocentric forces that are at work in society. The result is either a worship of, or at least an absolute reverence for, nonhuman animals as possessors of godly or Godlike qualities. The romantic perspective sees nature as something holy and untouched by the evils of human manipulation. Contact with nature (and, more specifically, nonhuman animals) creates, as John Rennie Short describes it, “a more pronounced spiritual awareness” (10) in the individual. Classical and romantic forces are at work in the texts of Grizzly Man, Bear, and Equus. In all three, romantic forces drive each of the protagonists’ actions to seek her or his own Eden. The God-given authority over nonhuman animals is not enforced, as the protagonists view nonhuman animals as either divine, revered, or, at the least, equal.

It is important to establish the terms of the traditional, biblical Eden, so that the variance of the created Eden in the three texts of Grizzly Man, Bear, and Equuscan be distinguished. In the biblical Eden, the LORD God gives authority to human animals to rule over nonhuman animals, including creeping things and creatures of the air and sea. (Gen. 1:26) A serpent, a nonhuman animal, tempts the human animals into eating from a tree that is forbidden to them by the LORD God. (Gen. 3:1-6) As a result, the nonhuman animal serpent is cursed to eat dust and be at odds with human animals. Also, the human animals are banished from paradisiacal Eden (Gen. 3:24), female human animals suffer pains in childbirth (Gen. 3:16), and male human animals curse the earth, making their own life toilsome. (Gen. 3:17-19) The nonhuman animal serpent, in this manner, attempts to rule over the human animals by controlling the human animals’ actions and forcing the human animals to share in its deception, reversing the God-given authority. In the three main texts of my argument, Grizzly Man, Bear, and Equus, the protagonist of each attempts to find a modern Eden–not the antiquated Paradise, but a personal, romantic Eden. In each individual’s attempted return to Eden, there is a breaking down of the boundary between human animals and nonhuman animals. In each individual attempt the romantic Eden is also ephemeral, and the environment proves impossible to sustain.

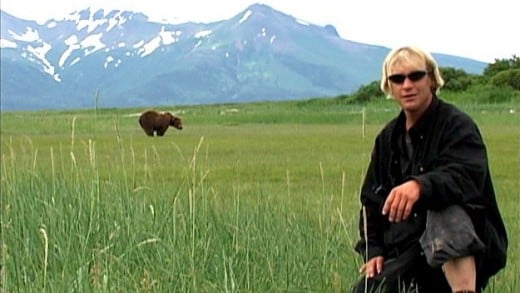

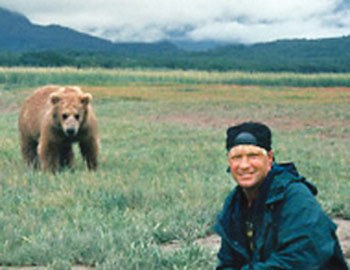

In Grizzly Man, the return to a romantic form of Eden is most evident. Timothy Treadwell rebels against society, and breaks down the anthropocentric tendencies of human animals to exploit and dominate nonhuman animals, by choosing to go to Alaska and live with grizzly bears. He names the bears, befriends them, even seems their maternal protector. This is obviously not a biblical Eden. A simple return to Eden would mean that Treadwell holds a positively authoritative position over the bears–this is not true in Treadwell’s situation. Treadwell’s relationship with the bears is instead more communal, even to the point that he metamorphoses, taking on characteristics of bears. Larry Van Daele describes Treadwell’s comportment as bearish: “He would act like a bear. He would woof at them. He would act in the same way a bear did when they were surprised.” Treadwell’s version of paradise is being in a family of nonhuman animals, being in a place in which human and nonhuman animals live in and respect nature, equally, in the presence of God.

Where is God in Treadwell’s self-built rendition of Eden? In his filming, he proclaims his agnosticism: “I have no idea if there’s a God.” However, his next statement leans toward belief: “But God would be very pleased with me.” Treadwell’s lack of religious affiliation leads him to seek holiness in the bears–his communion with the bears, and longing to become them, embodies his romantic perspective to view nature as holy. Treadwell’s desire to metamorphose reveals the rejection of his humanity (due to the cruelty that he associates with human society) in an attempt to attain holiness through nonhuman animal nature, as Marnie Gaede aptly explains: “He wanted to become like the bear. Perhaps it was religious but not in the true sense of religion.” Were the bears Treadwell’s gods? According to director Werner Herzog, in Treadwell’s mind, “Perfection belonged to the bears.” This perfection of the bears grants them a status of deity (Christ is likened to a spotless Lamb [1 Pet. 1:19]), or at least godliness. Treadwell embodies the romantic perspective by finding a deeper spiritual connection in hisnaturistic communion with the bears, which bears he may or may not deify for his own needs.

Treadwell’s attempted return to Eden is traumatic, and ends in death. Herzog describes the barren, jagged peaks of ice that surrounded the grizzly camp as being a “metaphor of his soul.” Treadwell is constantly disillusioned by the classical forces that invade Eden: nature photographers, uninvited guests, native naysayers, even the cruel end of summer when society beckons to him again. Treadwell breaks laws for being too close to the bears and staying at one camp too long, and the ensuing battle with the Park Service takes on a microcosmic metaphor: “There’s a larger more implacable adversary out there: the people’s world and civilization. He’s fighting civilization itself.” These classical forces at workare the serpent that steals the illusion, and destroys the permanence, of Treadwell’s Eden.

In Marian Engel’s Bear, the protagonist Lou develops a relationship with Bear on an island that isolates them from society, creating an Edenic environment for human and nonhuman animal to intimately commune. There is a stripping down of classical and anthropocentric forces just as there is in Grizzly Man. Lou reveres the Bear as holy, and Cary’s Island becomes their Eden. The island compares to the biblical Eden in that the nonhuman animal is present before the human animal arrives. On the other hand, the island reverses the biblical Eden, in that Adam and Eve are banished from the garden for their sin, while Lou forces herself to go tothe garden for her sin: “Then, for her sins, [she] went to the garden and worked for an hour, painfully weeding.” (80) Engel intends to show an Eden in which everything is reversed. Namely, Lou’s love relationship with Bear is an absolute dismissal of an authoritative position held by human animals over nonhuman animals in the biblical Eden. Furthermore, Lou considers Bear to be her God and, at the very least, her equal.

Lou identifies Bear as an alleged, deified being: “She felt sometimes that he was God.” (102) This may stem from her intermittent readings of Colonel Cary’s bear lore which she finds stuffed randomly in books, including snippets from bear myth. The most obvious instances of references to bear deity that Lou comes across are notes which mention a bear god in Irish folklore (58) and a claim that bears were the true progenitors of human animals: “It is rumoured that even the pious pay [bears] reverence in view of the ancient belief that they, not Adam and Eve, were our first ancestors.” (59) This symbolization of bear as God is also evident in the twelfth century Latin bestiary, in which the word ursus is associated with the word Orsus, or, “a beginning.” [9] The fact that Bear precedes Lou on the island, in like fashion, makes Bear symbolic of being an original creature.

When Lou is less cognizant about Bear being her God, Lou deems Bear at least her lover, as Lou herself calls him. (96) Lover status makes the nonhuman animal her equal. This is an obvious cancellation of anthropocentric forces, resulting in Lou’s romantic relationship with nature and Bear. According to Lou’s discovered bear lore, the Norwegians called bears, “Moedda-aigja,” or, “the man with the fur cloak.” (85) This is an obvious amalgamation of human and nonhuman animal characteristics that Lou projects onto Bear, making them compatible in her eyes.

In Peter Shaffer’s Equus, there is an unmistakeable glimpse of a romantic Eden. Alan Strang hybridizes his own personal religion, in which he worships Equus, who is a horse-spirit present in all horses. Alan’s communion with Nugget the horse, in whom the spirit Equus lives, is an intimate and erotic communion, linking a spiritual form of ecstasy with his religion. Alan recalls his passionate excursions with Nugget in which he sheds all his clothes, fondles Nugget amorously, and rides it naked in a dark wilderness. (act I, scene 21) The recreation of Eden is most evident in these midnight jaunts with Nugget. Alan and the horse are both naked, just as Adam and Eve lived naked with the animals in the biblical Eden. If Alan communes with his god Equus, who lives within Nugget, and he is alone with Equus in the field of Ha Ha (act I, scenes 20-21), then this also conflates with Eden, because God walked with Adam and Eve in the biblical Eden. (Gen. 3:8)

In Equus Doctor Dysart represents an extreme classical force of society which ultimately removes the romantic force of Equus from Alan’s life. Ultimately, Alan is exiled from his Eden due to his blinding of six horses with a metal spike, after which he undergoes psychiatric therapy with Dysart–the prospective outlook at the end of the book is that the classical forces of society will dominate Alan and he will be inculcated to adhere to its norms.

Alan’s removal of clothing is also equal to a removal of classical forces and, ultimately, Alan’s nudity melds him with the romantic, animal world. Clothing as a threshold between human and nonhuman animal planes of existence is an idea that stems back to the Medieval lays, like Marie de France’s “Bisclavret”, [10] in which Bisclavret must keep his clothing hidden, because his clothing is what links him back to human life and the civilized world. Alan hides his clothing before riding bareback on Nugget in the same manner. (Act I, scene 21) The removal of clothing, and bonding with the horse while naked, makes Alan as nonhuman as physically possible, and as close to his God as is humanly possible. Unfortunately, Alan’s Edenic relapse is irrational and momentary. Again the romantic Eden is met with inescapable classical forces.

Suzanne Schiffman’s film, Sorceress, [11] can be drawn parallel to Equus. Sorceress portrays a similar mingling of divine power with a nonhuman animal, namely the dog-saint Guinefort, who is accidentally martyred after saving a child from a serpent. The belief that Guinefort possesses spiritual powers and ability to protect children contains elements of animalism-Alan Strang’s worship of Equus is similar in that it is a hybridization of Christian practices and animalism. In both instances–the medieval and the modern–there is a confluence of deity and nonhuman animals. This can be associated with medieval influences, when in the thirteenth century nonhuman animal stories, including fables and bestiaries, were incorporated into Christian sermons. [12] Jesus Christ, God the Son, is likened to multiple nonhuman animals in the twelfth century Latin bestiary, such as a lion, panther, and a unicorn. [13] In this case the nonhuman animal symbols were used in the Middle Ages to push classical motives of proselytization. These modern stories possess aesthetic attributes in which God and nonhuman animal are similarly amalgamated, yet now from a romantic perspective.

Lynn White, Jr., states, “By revelation, God had given man the Bible, the Book of Scripture. But since God had made nature, nature also must reveal the divine mentality.” [14] If God is the creator of both words and weeds, there will always be a fluctuation in the human heart, a constant ebb and flow by which humans will have to choose between the words that make the laws of society, and the weeds that make up the wilderness. Eden, as it was originally intended, may be impossible to recreate, yet the serpent lives in many a backyard. The individual Eden of Treadwell, Lou and Alan could not be sustained. Was that not true of Paradise?

From the serpent in Eden onward there has been a challenging of human animals’ God-given authority to rule over non-human animals. One with a romantic perspective would say that the way back to God is by relinquishing that God-given authority, and by serving nature and nonhuman animals. Maybe Treadwell, Lou and Alan were onto something. Maybe there’s an Eden for everyone, and that it must be found. One with a classical perspective would argue that there is no way back to God, but that God is forever before us, and by serving society and human animals, progress will bring civilization to God.

One thing is certain–in Eden, human animals were as close to nonhuman animals as they ever were, or will ever be. They were comfortably naked, and they were oblivious to good and evil.

1Werner Herzog, Director, Grizzly Man, 2005.

2Marian Engel, Bear (Jaffrey: Nonpareil, 2010).

3Peter Schaffer, Equus (New York: Scribner, 2005).

4Joyce E. Salisbury, The Beast Within: Animals in the Middle Ages (London: Routledge, 2011), 1.

5Introduction, in Jean-Claude Schmitt, The Holy Greyhound: Guinefort, Healer of Children since the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 2.

6T.H. White, ed., The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation from a Latin Bestiary of the Twelfth Century (New York: Dover Publications, 1984).

7“Wilderness,” in John Rennie Short, Imagined Country: Environment, Culture and Society (London and New York: Routledge, 1991), 4-27.

8Lynn White, Jr., “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis,” Science n. s. vol. 155, no. 3767 (March 10, 1967): 1203-1207.

9White, Book of Beasts, 45.

10“Bisclavret,” in The Lays of Marie de France, trans. Edward J. Gallagher (Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 2010), 29-33.

11 Suzanne Schiffman, Director, Sorceress, 1987.

12Salisbury, Beast Within, 98.

13White, Book of Beasts, 8, 15, 21.

14White, Jr., “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis,” 1206.