The Literature of England's Industrial Revolution

England’s Industrial Revolution began in the mid-18th century and had a profound impact on history, and especially on literature. From all the suffering caused by the rise of the factories, one good thing did emerge – a new form of literature, based on the common man and imagination.

Before the Industrial Revolution, England was a land of small farms and cottage industries. Most of the country folk lived on a few acres and grew vegetables, grains, and a few head of livestock. Their cattle and sheep usually grazed in communal pastures owned by the state. The cottage industries were small family-run businesses that produced goods like candles, lace, clothing apparel, pottery, wheels, wagons, leather items, and other articles used on an everyday basis by the general population. On weekends and market days, the cottage industry owners took their wares to town to sell.

Of course, none of the owners of these cottage industries became wealthy from their small businesses, but they were able to survive. They grew much of their own food, and when they needed something they couldn’t grow or make themselves, they either sold something to earn the money to buy what they needed, or they used the barter system.

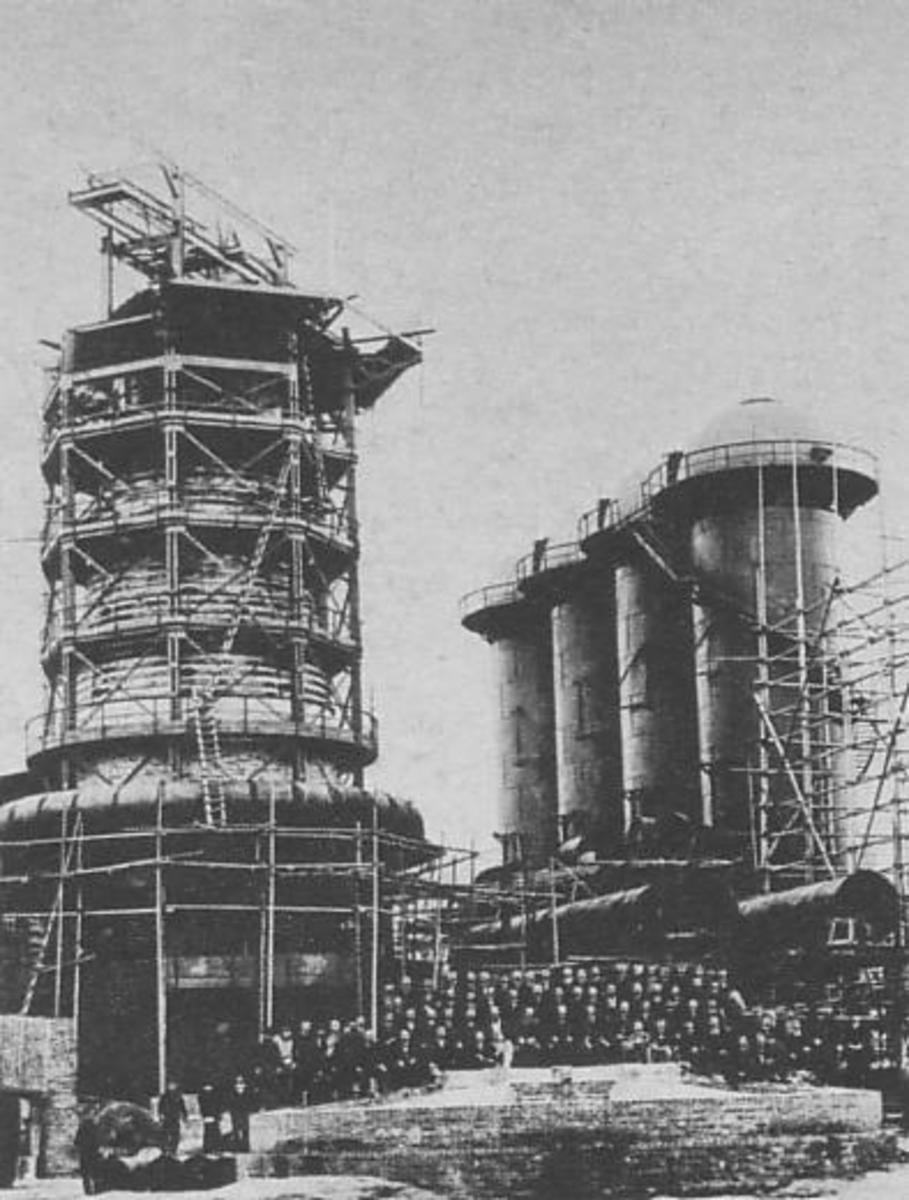

Once the factories began mass producing such items, the cottage industries were put out of business. Factories could produce the goods faster and cheaper, so the home business owners were put out of work and left with no income. They had little choice but to move to the big industrialized cities like London or Liverpool to find employment in the very factories that put them out of business.

The Industrial Revolution also had a profound impact on small farmers. The communal grazing lands that had provided much of the food for their cattle and sheep were taken over by the state and turned into private hunting lands for the aristocracy. Since the poor farmers now had no way to feed their livestock, they were put out of business, too – just like the cottage industries. And like the home business owners, the farmers had little choice but to move to the cities to work in the factories.

For those who refused to leave their homes, or for those who couldn’t find factory work, their only other choice was to go on public welfare, referred to as “the dole.”

Conditions in the factories and in the cities that supported them were deplorable. Employees had to work long hours, six days a week, in dangerous conditions. The government turned a blind eye to all this, and a policy of laissez-faire was followed. “Laissez-faire” is French for “let them do as they please.” In other words, there was no government intervention in the running of the factories. It seems as long as the factories were adequately producing, the state cared nothing about the workers. Safety laws and child labor laws were nonexistent.

The living conditions of most of the factory workers were crowded and filthy. Several families might share the same flat, and more than a hundred individuals often had to share a toilet. When the Window Tax was imposed, the workers couldn’t even afford fresh air or sunlight. Windows were nailed shut and painted over to avoid paying the tax. Most factory workers lived and worked in utter misery, seeing no escape from their drudgery.

Poets like William Blake detested the Industrial Revolution, and many of his poems echoed this sentiment. Other poets followed his lead. In 1798, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge emerged on the scene when they published a book of poems entitled Lyrical Ballads. The two young writers broke with the writing traditions of the past by focusing on the common people and on the imaginative powers of the human mind. They spoke to and for the factory workers and others who felt helpless and powerless. They also drew attention to the plight of the downtrodden and abused, which gradually led to improved working and living conditions.