The Long Way Home: Walking Through Boston the Day of the Marathon Bombing

The subway train from North Station was almost empty. The mood on the train was sullen, most of the few passengers sunk heavily in their seats with their heads down, though one could see exhausted people riding the train around quitting time any day. Two women in work uniforms jabbered at each other in Spanish, but from their glances directed above the doors it seemed their conversation centered on the subway system map rather than the day’s events.

The Green Line had been closed in most of the city, from Government Center downtown to Kenmore on its western edge. My company’s office is right outside North Station, near Boston’s North End at the mouth of the Charles: from our sixth-floor windows we can see the obelisks of the Lenny Zakim Bridge to Charlestown with their piano-string suspension cables swerving down, and the Bunker Hill Monument that they echo in the distance. This train originated at Lechmere Station in Cambridge and stopped at Science Park on the Boston riverbank before North Station. I suppose most people who normally would have boarded at those stops had either taken taxis, hitched a ride with someone else, or felt that the brief ride to Government Center before having to walk wasn’t worth the bother or wait.

Where the journey began.

After Haymarket station, we all deboarded at Government Center into a normal-looking scene above ground, with streams of pedestrians issuing from City Hall, the courthouses, and the Financial District—except few of them entered the subway, and the abundance of police officers made themselves highly visible. Out-of-towners here for the marathon, some with foreign accents, asked the cops for directions; runners still in their foil capes glittered in the throng like flecks of silver. In spite of authorities’ requests to conserve bandwidth and spotty service due to overload, about half the people I saw were talking on their cell phones. Traffic was heavy but brisk on Tremont Street heading out of downtown toward the South End. A black unmarked van with sirens blaring raced past and a Cambridge Police bomb squad car (other cities and towns were sending emergency personnel to help) pulled up along Boston Common just beyond Park Street subway station, but no one got out.

From Park Street, I walked through the Common in a concave arc, passing the empty gazebo-like bandstand, the back of the memorial to the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment, and the Frog Pond. On the paths crisscrossing the open green, people walked in small groups, with a scattering of odd loners like me. They wore the self-assurance of those who know their surroundings, but drifted slowly enough to seem lost.

I crossed Beacon Street near the park’s opposite corner where Charles Street, separating the Common from the Public Garden, meets Beacon. I fell into a cluster of foot-travelers consisting of a cadre of middle-aged friends, two men and two women, and a young Asian couple with a pair of toddlers—older boy and younger girl. Members of each bunch conversed among themselves but not, despite our shared plight, with its counterpart or me. There was nothing more to say than the obvious.

It had been sixteen years since, arriving in Boston shortly before my first year of graduate school at Emerson College, I would kill time in the late afternoon following a day spent hunting for an apartment and a job walking all the way from Park Street station down Beacon Street to the Boston University dorm just west of Massachusetts Avenue that Hostelling International rented for the summer. The buildings here stirred blurry memories—the Bull and Finch Pub, inspiration for the sitcom Cheers, at the foot of Beacon Hill; my old stomping grounds in Emerson College’s student union, computer lab, and former library, which had also been Isabella Stewart Gardner’s home before she moved to the site of the museum that bears her name in the Fens; the Scientology headquarters; the quasi-Gothic church on the corner of Mass. Ave., diminutive and ornate as a toy palace; the exclusive apartments carved out of the Brahmins’ three-story brownstones; the high-Modernist house at the end of one block with yellow walls, flat roof, and dipping concrete overhangs above each floor, sticking out from Victorian Back Bay like Walter Gropius’s sore thumb. It felt like another person had seen these things then, in another life, when income and shelter were the biggest anxieties the city could give me. Now, the old row houses themselves looked as if bracing against hostile surroundings: their cramped plots girded with spiked iron fence staves, front doors deep in the recesses of projecting architraves resembling igloos’ entryways, turrets jutting out and rising up the houses’ whole height like castle keeps. Yet those fences enclosed gardens vivid with red tulips and pastel blue hyacinths, shaded by the white blossoms of dogwoods and the cool green needles of young spruces. The Muddy River trickling through the Fens into the Charles looked unusually clear, belying its name.

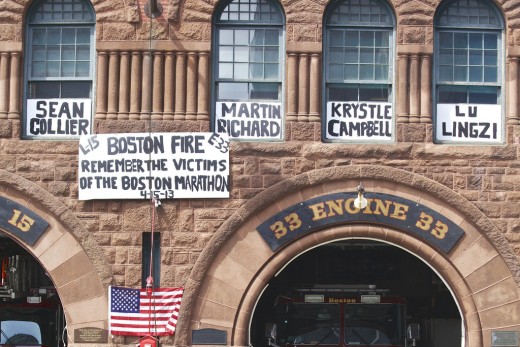

I kept to Beacon Street to give the bombing site a wide berth, but at Dartmouth Street I could see the flashing red lights four blocks down at Copley Square. I had seen enough of the missing limbs, the blood on the pavement, and the smoke in the air on the Internet. At work, I had come back from the men’s room a little after 3:00 p.m. when my co-workers told me about the first explosion, which they had learned about online—only minutes after it happened. Then came the second explosion, making me suspect foul play before the announcement that the explosions had been caused by bombs. Soon, the MBTA closed the Green Line, which runs by the marathon’s finish line. By 4:45 an explosion had been reported at the John F. Kennedy Library at the southern end of Boston Harbor, which turned out to have been an accidental fire; word also came over cyberspace of a bomb found at the Harvard Square subway station in Cambridge, which I found out when I got home was completely false. Everyone in my department decided to leave. I e-mailed our manager, who works out of New York, “I don’t know if you heard down there about the bombing at the marathon, but we’re taking off.” The next morning, his reply awaited me: “Sure.”

Friends dawdled or huddled to talk on porches; parents sat with their elementary-schoolers on the raised stone borders of the houses’ courtyards. The children smiled and sang songs they learned in school. Had their parents told them anything about what happened? How could they try to explain to the children what we adults didn’t understand? Calm prevailed among everyone, a lull resulting from stress subsiding after adjusting to disaster’s emergence and waiting for what we would hear next. No one showed fear, or hurt, or anger. Probably no one wanted to seem afraid to others, and it might still have been too early for hurt to set in on us who weren’t touched directly by the explosions. As yet, we didn’t have any likely suspects to be angry at. Most of all, as sudden and horrific as the bombing was, no one looked shocked. We couldn’t be shocked. It had been a long time ago, in another place and on a greater scale, but we all knew we had been through this before.

By the time I reached Kenmore Square, vehicular traffic had all but disappeared, affording a quiet that otherwise would have been more than refreshing. Urban legend has it that at least one person a year is killed by a car at this awkward crossroads, where Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue intersect at a thirty-degree angle and Brookline Avenue—which, early in my residence here, I had mistaken for the continuation of Beacon Street and perplexed myself immensely—shoots out to the southwest. This afternoon, though, dozens of people strolled through the square at their leisure.

The B and C routes of the Green Line, closest to my apartment in Brookline, were closed beyond Kenmore as well, so I detoured slightly (the different tracks stay ridiculously close to one another) toward Fenway, the D train’s first station after the Green Line splits and its first ground-level station. Turning onto Brookline Avenue, I found myself bucking the tide of fans leaving Fenway Park by Lansdowne Street and Yawkey Way decked out in T-shirts, jerseys, and caps in red, white, and blue, the colors of Red Sox Nation. As they laughed, shouted, and finished their plastic cups of beer and soda, I couldn’t fathom how the atmosphere of fun persisted among them as after any other ball game; I couldn’t fathom how the game had been allowed to proceed.

As I crossed Landmark Center mall’s parking lot to Fenway station, a train was paused at the platform—I ran and caught it. This one was crowded, collecting the droves of those who had plodded through the city to the only subway line still running to Brookline and Newton. My friend Rich Snyder, who works in the Financial District several blocks down Court Street and State Street from Government Center, was also riding this train, and it relieved me after prolonged silence among strangers to find someone I knew and compare our stories of the afternoon while time permitted. I must not have been the only one who had felt alone in the crowd: a young woman standing on Rich’s other side inconspicuously leaned in, keeping her eyes on her book, to listen as we spoke until we arrived at Beaconsfield, four stops later, and I left the train to walk the last three blocks home.