The Narratives of Equiano and Douglass: Writing and the Event of Becoming

Olaudah Equiano’s “Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano” and Frederick Douglass’ “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass” are two of the earliest autobiographical novels in the African American literary tradition. Prior to the rise of the novel African American oral traditions created "the chief bond between [African Americans]" which had been characterized by "a common condition rather than a common consciousness; a problem in common rather than a life in common" [italics added] (Mitchell, 1994). Thus, the subjects of African American vernacular traditions constituted very general figures such as "me and my gal," "Jesus," "Moses," and the first person "I," which essentially stands for a general, fictionalized self rather than any particular character (Gates, McKay, 1997). The autobiographical novel, however, had the leisure of space and time to allow authors to expound on the details of details into their narratives, which created a specificity of language and description typically absent from the poetic oral traditions. Thus, when Equiano and Douglass used the first person "I" in their autobiographical narratives, the "I" became a living, breathing character— not merely a cultural or racial shadow. It is this notion of creating oneself through writing that is so powerful and moving for readers.

The Power of Equiano and Douglass’ Narratives

The autobiographical novels the “Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano” and the “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass” are meaningful because they show how writing fosters a unique creation of the “I.” The African American experience, especially during the Antebellum and Reconstruction periods, could be characterized by bitterly fought self-identity crises. The major issue for 18th and 19th century African Americans was: "what do we call a subject who is both more or less an individual and stronger and weaker than a free agent?" According to literary critic, Dorothy Hale, the answer is "a voice" (Hale, 1994). Hale says that "thanks to its metaphoric flexibility, the term can describe human identity as unproblematically self-selected and socially determined, both individual and collective, natural and cultural, corporeal and mental, oral and textual" (Hale, 1994). The rise of the autobiographical novel in the African American literary tradition indicates an important shift from cultural collectivism to individualism. The African American “I” was born in flesh and blood for the first time in the English language through particular “voices.”

New Historical Approach to Equiano and Douglass’ Narratives

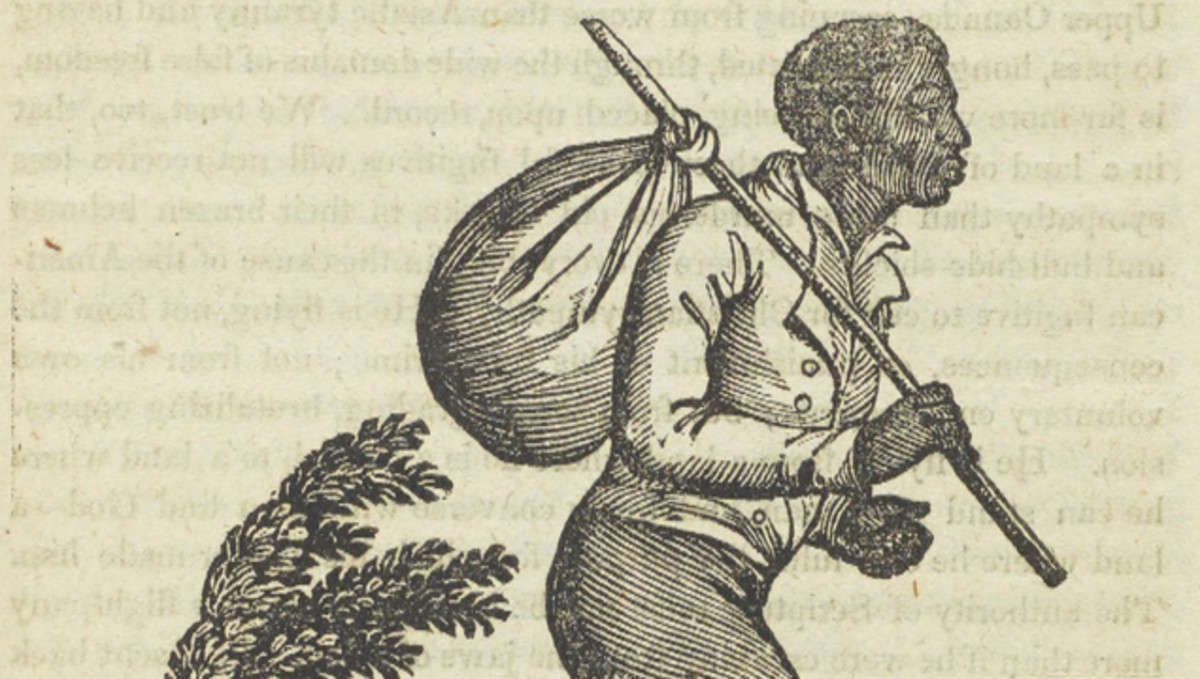

Both Equiano and Douglass lived in slavery. Thus, it is no surprise that “the engendering impulse of African American literature is resistance to human tyranny” and “the sustaining spirit of African American literature is a dedication to human dignity” (Gates, McKay, pg. 127). From this racial desire for justice, equality, and freedom helped to ignite the African American literary traditions in the English language in the form of spirituals, gospels, secular songs, and the blues. These efforts helped create a communal voice for African Americans. These efforts, however, had more personal significance for African American individuals rather than a wide-spread American political significance. Despite how the vernacular tradition recognized the inherent contradictions in American ideals, such as “the ideals of equality and liberty celebrated by the founders of the United States,” and effectively united African Americans through a common condition—their ability to persuade the United States government was nullified because the African American literary culture was primarily oral (Gates, Mckay, pg. 127); the official realm of Western politics was fought in—what the literary theorist Jacques Derrida called— the “logomachy,” or the world of printed (not necessarily written) script (Ong, 2003).

For this reason, the African American individual did not exist yet to the United States government because slaves were not taught to read or write. Essentially, to read or write was to participate in the official realm of communication where there are circles of special knowledge such as law, education, and economics (Ong, 2003). This exclusion of African Americans from the English language was aimed to keep African Americans from realizing their intellectual potential to rebel against the institution of slavery.

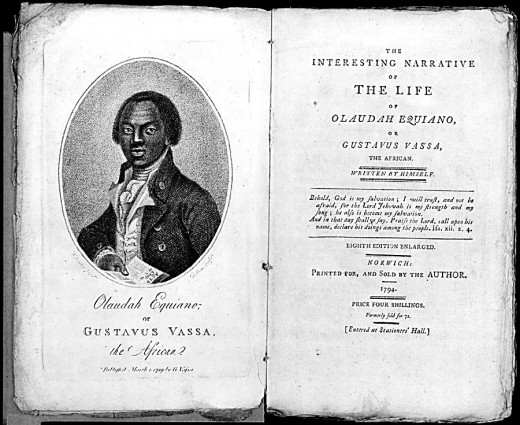

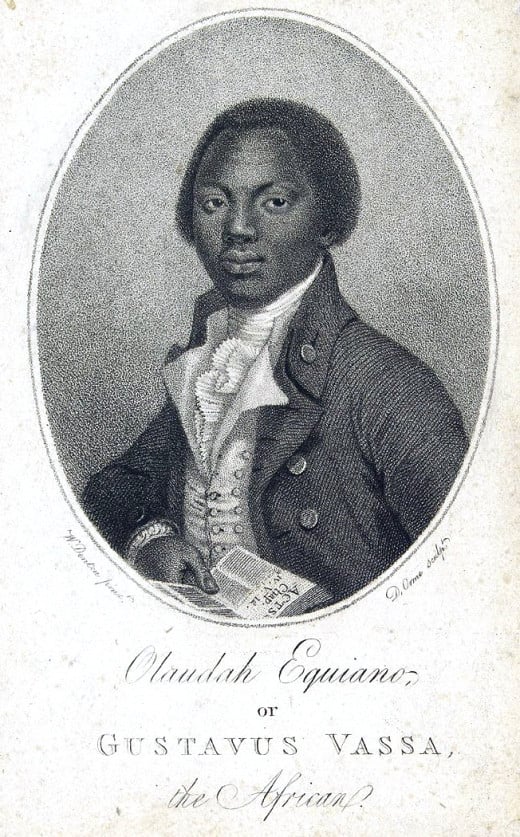

Equiano’s Prototype

Equiano set the stage for further development of the slave narrative when he completed his “Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano” by transcending the barrier of oral literary traditions into the official world of the logomachy. This feat helped African Americans and abolitionists verify the claim that “blacks could represent themselves effectively through writing” which was a claim “much disputed during the Enlightenment” (Gates, McKay, pg. 138). By launching the African American literary tradition into the logomachy through the highly personalized form of the autobiographical slave narrative, Equiano finally accomplished the arduous task of separating his I from his race. In other words, he enabled the creation of the African American individual.

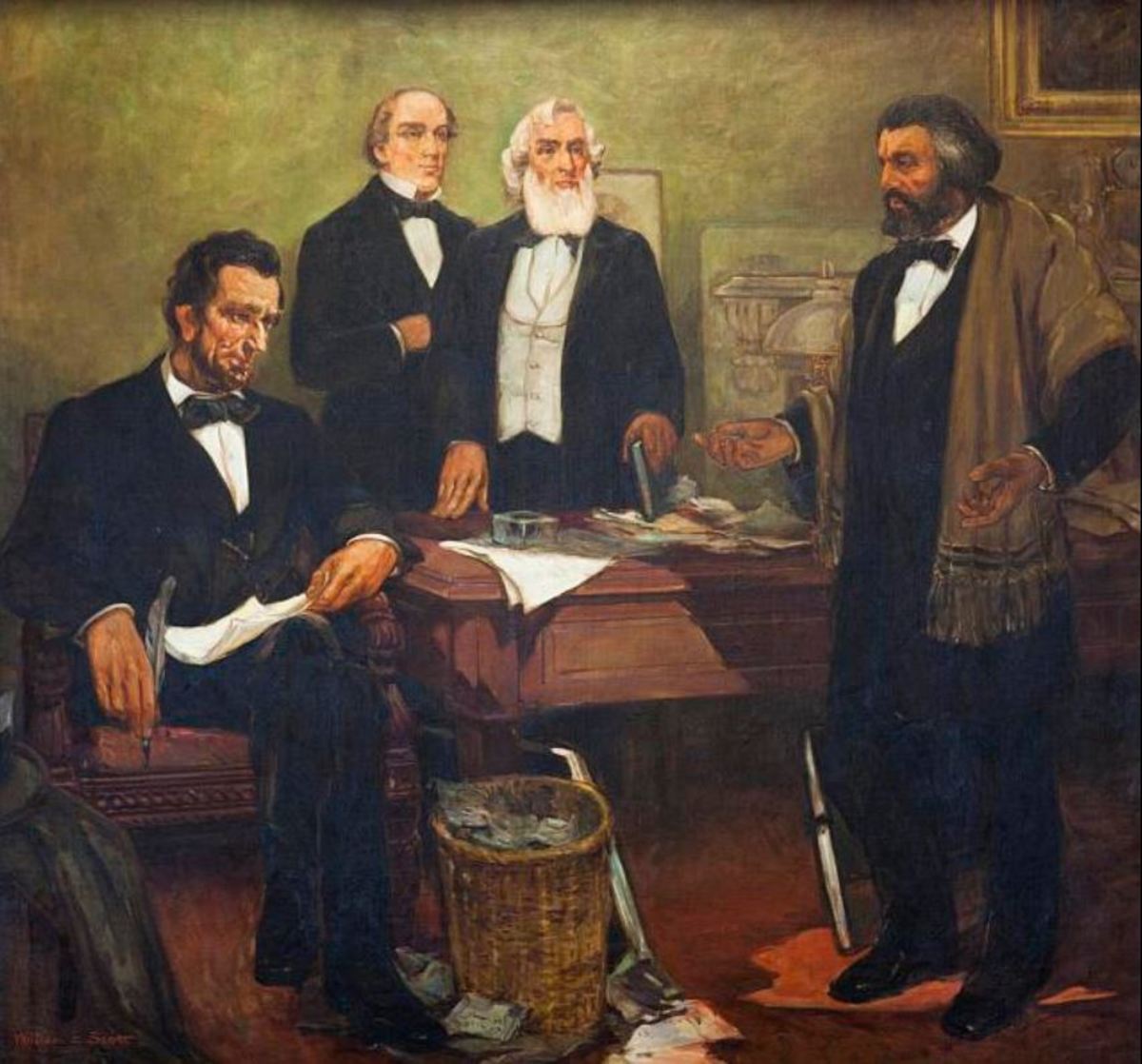

The prototype Equiano created with his autobiographical slave narrative influenced several African American writers between 1776 and 1850, the time between the Declaration of Independence and the advent of the American Civil War, such as Sojourner Truth, William Wells Brown, and Harriet Jacobs; however, perhaps no other African American author perfected the autobiographical slave narrative better than the passionately vocal and prolifically written author, Frederick Douglass.

The Power of Language

The literary development initiated by Equiano and perfected by Douglass, the slave narrative, was a prime mover in the elevation and liberation of African Americans from the bondages of slavery by situating the African American voice into the realm of the logomachy. Furthermore, the slave narrative helped create a living, breathing "I" for African American authors and readers alike. The way Equiano and Douglass acquired and mastered the English language show how language itself harnesses tremendous power: personally and politically. The ability to communicate in the official realm of published script is a testament to one's unique individuality and intellectual potential because it shows the autonomy of his or her thoughts. To write is to create something new and unuttered. This is why Equiano and Douglass' narratives are so meaningful to me. I view language as a very powerful tool; "with great power comes great responsibility" (Ditko, Lee, 2002). I see language as a potential tool that can help resolve many contemporary issues and injustices ranging from foreign wars to domestic and animal abuse.

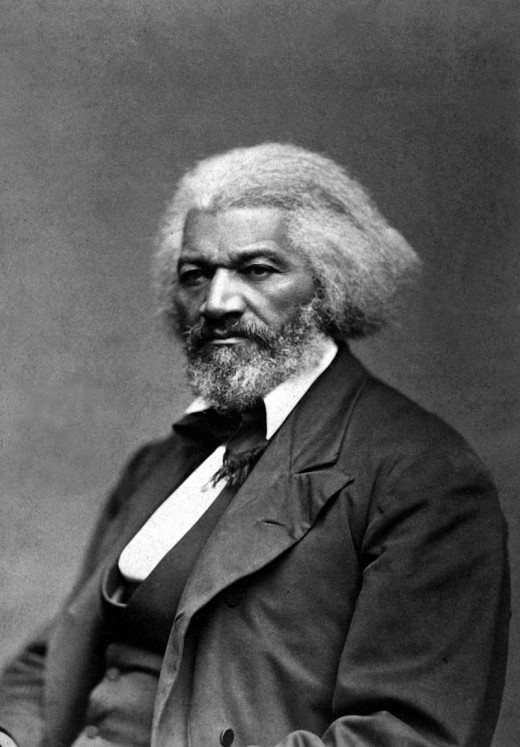

Douglass’s Mastery

Through Douglass’s “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” he created his unique “I,” which the black physician and abolitionist, James McCune Smith, described as a “record of ‘self-elevation’ from the lowest to the highest condition in society” (Gates, McKay, pg. 299). James furthered his commendation of Douglass saying that he was a “’notable example’ for all Americans to emulate” [italics added] (Gates, McKay, pg. 299). Smith’s praise for Douglass is very significant because it implies that the acquisition of the abilities to read and write is to achieve a state of “self-elevation.” Furthermore, the mastery of these abilities makes an individual a “notable example” for everyone to follow, not just other African Americans. What greater quality could one have than a voice so powerful that it could help liberate an entire race of enslaved people? Ultimately, Douglass’ mastery of language and rhetoric allowed him to fight for the African American individual by both representing the potential of his race and by exemplifying the highest pinnacles of human intellectuality in his own “I.”

References

Ditko, S., Lee, S., (2002). Spiderman (directed by Sam Raimi). Columbia Pictures Corporation; Marvel Enterprises; Laura Ziskin Productions.

Gates Jr., H., McKay, N., (1997). The Norton Anthology of African American Literature (1st ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Mitchell, A., (1994). Within the circle: An anthology of african american literary criticism from the harlem renaissance to the present. London, UK: Duke University Press.

Ong, W., (2003). Orality and Literacy. New York, NY: Routledge .