The Rise and Fall of the French Air Force Review

The French Air Force has often been just as poorly served by history and writing about it as it itself was served by fate in history, which is why The Rise and Fall of the French Air Force: 1900-1940 by Greg Baughen makes for such a thoroughly brilliant reversal of the previous trend with a scintillating and superbly done book about the development, doctrine, operations, and employment of the French Air Force, magnificently covering its development in a lengthy and consistent narrative from even before the first aircraft took to the sky to its defeat over the battlefields of France in Spring 1940.

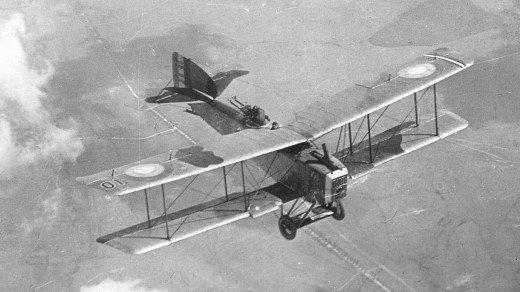

"The Seeds of Future Problems", the first chapter of the book, discusses the initial development of the French air force, starting with balloons, blimps and working its way up to the First World War, where the French focused on the idea of large, multi-crew aircraft for reconnaissance duties, with the need for small, single-engined and single-seat fighters only desperately making itself clear. The French had ups and downs in their air war against the Germans, winning air superiority over Verdun but also failing in other battles like during the Nivelle offensive.

Chapter 2, "Towards a Modern Airforce" underlines the triumph of the French in 1918 when their combination of advanced bombers, single-seat fighters, and reconnaissance aircraft proved capable of winning air superiority and conducting operations during the tense period of early 1918. Here the French were able to, when all seemed almost lost during the German Spring Offensive, conduct devastatingly effective offensive ground support operations against German ground units, providing an important contribution to victory. At the same times, the seeds of future problems would be laid, as this would be discounted and the French began to place more focus on large multi-crew bombers and strategic warfare, viewing the mobile warfare of 1918 as an exception which would not be repeated again.

Chapter 3, "The Air Force Loses its Way", covers the immediate post-war years, where the shape of the French air service was laid out, focused on long range bombing (although it continued to e focused on tactical operations, with limited strategic defense), and the French continued to plan to have a powerful air force to fight Germany - while it fell in side, it was still very large indeed. The army continued to want fighters strictly controlled by itself, but the total number of fighters were being reduced. These fighters would be increasingly focused on high altitude performance. Furthermore, the French gradually turned to large, multi-crew, multi-engine planes, multi-purpose, and their lead in high speed flight evaporated. The importance of tactical operations in Morocco where the French air force played an important role in the Rif War did little to change these trends.

Chapter 4, "The Bomber Rules", tackles the increasing obsession with strategic bomber warfare, which helped to lead to the development of an independent French air force most concerned with an ideal of all-out, total, strategic air warfare. The army opposed this, but political battles ultimately favored the strategic policy. Air strength would be oriented towards the strategic role, with multi-role aircraft known as BCR (bomber-combat-reconnaissance), supposed to do essentially everything and hence to fulfill both strategic and the still army-mandated tactical roles. Although the French later tried to build high speed bombers, they would focus on radial engines, which they were ill equipped to put into mass service.

Chapter 5, "Fighter Design: Squandered Opportunities" looks at the disastrous state of French fighters in the early 30s, where a long obsession with high altitude performance had led to slow fighters that would be easy pickings for enemy aircraft at most combat zones. The French started to focus on speed, but with insufficient ambition, and the British and French soon started providing targets or performances that vastly exceeded their own aircraft speeds, although French fighters tended to be superior in other aspects. Still, the French were broadly groping towards an air force that might work in 1940, with lots of fighters and capable bombers usable both tactically and strategically.

Unfortunately this would not be permanent, and the French, as related in Chapter 6 "Back to the Bomber", when the Germans moved into the Rhineland and the French, terrified about the prospect of the superior German bomber force destroying their cities from the air, didn't move and put their effort into building up strategic bomber forces once more. The air force was quickly reorganized with a strategic focus, and ironically efforts to expand the battlefield intervention force was opposed by the army, which preferred reconnaissance aircraft.

Chapter 7, "Chaos Reigns", relates the difficulties the French had in trying to build up their bomber force, running into problems with the troublesome LeO 45 bomber, advanced but problematic. In fighters too, the French were having difficulties keeping up due to design errors. All of this was compounded by the decision to nationalize the air industry, which caused temporary chaos, amplified by poor French ordering policies which prevented production expansion. It was not until 1937 that the French began to take seriously the need to build up their fighter forces and to truly start to re-arm beyond just their strategic bombers.

"Time to Rearm" as Chapter 8 is entitled, discusses Plan V, the French plan to build a tactical-focused air force with a heavy fighter contingent, supposed to be ready by 1940 with massive increases in aircraft production and large purchases of aircraft from the US. The French faced shortages as well in engines and pilots. and their bomber procurement efforts were confused and halting.

Chapter 9 relates the unfortunate result of this, in "To the Brink of War", as the French faced being dramatically outgunned in the air, with a continuing strategic deficit, by the Germans over the Sudetenland Crisis. With this, the French once again backed down, and Czechoslovakia abandoned. The French had bought time, which they put to use in further efforts to purchase aircraft and expand production, including of light aircraft and new fighter designs. In general production expanded and enabled an increase in front line strength, but the French were concerned that their aircraft were once again falling behind in quality, resulting in orders for new fighters like the D.520. The French had made great strides overall, although their bomber force continued to be exceptionally outmatched.

Unfortunately this assurance proved unfounded, as "From Confidence to Panic" relates, as the French moved to new production and ran down older aircraft like the MS.406. Major production effort went into new long ranged bombers, reducing fighter production. If the French didn't suffer major losses as they anticipated early in the war, they also did not take advantage of the large numbers of foreign pilots who arrived from Czechoslovakia and Poland. Production fell, and the French did little to work to incorporate American production coming to France. German planes proved to be getting better and better with new BF 109 variants, much better than French planes, reinforced by the horrifying revelation that reports on the performance of the Bloch MB.150 had been exaggerated and it was in fact much worse than German aircraft or even the MS.406. Confusion, errors, and lack of focus had meant the French had spoiled their additional time, and they went into 1940 with a much smaller and much more ill prepared air force than they could have had, or indeed needed.

Chapter 11, "Desperate Measures" covers the last few months before war, when French production at last was beginning to increase once more, but with insufficient time to put them into service, and even those planes that were available were commonly diverted to secondary theaters like Syria or sold abroad. French planes had shortages of parts, and there were insufficient ferry pilots, this despite vast numbers of unemployed Polish and Czech pilots. The French entered May 1940 outmatched, and ill-prepared for what was to come, although if they held on long enough, production promised to even out the balance.

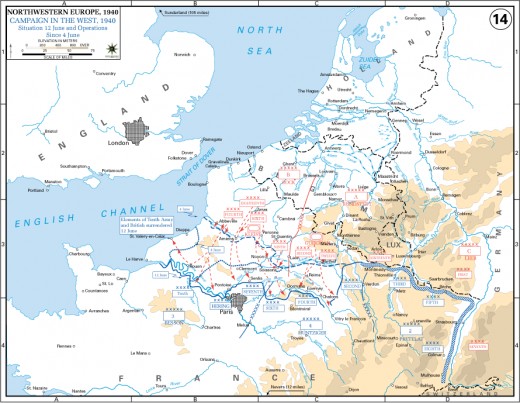

The question is, would they? Chapter 12, "Dutch Misadventure", relates the beginning of the war, with the Germans attacking a wide range of allied targets, including airfields. Some French fighters were destroyed, but not enough to cripple the French air force - unfortunately, there were no reserves to replace these, and overall the French air defense response, while shooting down a fair number of bombers, wasn't as good as it could have been. Allied response bomber efforts were to little effect, and little reconnaissance could be conducted because of German air superiority. However, the Germans took heavy air losses in the Netherlands. The Germans' sacrifices enabled them to make important gains however, while French units were defensive, spreading their fighters out to cover their cities, and surrendered the initiative to the Germans, especially given the failure to commit effective units in otherwise favorable circumstances like the Netherlands where their tactical bombardment units were not used effectively. The Germans were winning the battle.

Worse was yet to come, as "Disaster on the Meuse" relates, when the Germans broke through on a broad front from Sedan to Dinant, exploiting their aerial superiority and committing the Luftwaffe massively, and the French frantically tried to respond. They sent bombers to attack the German bridges which had been put up over the Meuse, but without result, due to German fighter superiority and mass concentrations of anti-aircraft artillery (the French delay in launching their attack enabled German AA to set up its positions), and even in this crucial moment, the French response was still notably lethargic. The disastrous state of the French air battle over this crucial section of the front would do much to doom France.

Chances still remained however, as related in "Missed Opportunities", for the French could, just as they had in 1918, send their forces in a tactical attack on the advancing Germans, sending everything they had to harry and destroy the advancing German columns. The French air force was suffering tremendously under the strain of war, and once again, it was unwilling to make a maximum intensity effort, with reconnaissance aircraft with secondary bomber functions unused for ground attack, while in contrast the Germans expertly organized even obsolete aircraft to oppose French counter-attacks. Attempts to support French ground operations against the Germans amounted to little. The Germans would reach the sea.

"Lessons Learned Too Late", the last and 15th chapter, covers the French efforts to defend their defense lines in the North, where increasing production seemed to offer some possibility to stem the Luftwaffe, if the French had time to put it to effect. The air force attempted to support counter-offensives to retake Abbeville, Amiens, and Péronne, but once again, these were poorly utilized - with the army often being disinterested in these efforts itself. German strategic bombardment raids happened on paris for the first time, and although these were a limited success, and were able to happen without sustaining great losses, they also showed that the fear of city-destroying strategic bombers had been misplaced, as it was nowhere near as damaging as feared. When the Germans attacked themselves on the ground, they had air superiority and the French were unable to truly make an important impact on the battle. The situation was disintegrating, and the decision was made to flee to North Africa with those planes that could, while remaining aircraft in France did their futile best to oppose the Germans up to the armistice.

The conclusion sums up the strategic trends of the focus on strategic bombardment and the deleterious effect this had on the French, as well as its influence in peace and diplomacy, and recaps some of the problems and issues of the French ranging from poor design choices, to difficult army-air cooperation, to lack of adaptability with older and obsolete aircraft.

There is no doubt on my part that this book will come to be recognized as a vital milestone on the understanding of the French air force, a subject which otherwise has relatively few high quality books which grace the matter. State Capitalism and Working Class Radicalism in the French Aircraft Industry has been an important book to understand problems associated with production, and French Air Force and Doctrine in the 1930s, a dissertation by Anthony Christopher Cain an excellent work on the subject, but still there is less literature available that one would wish. Here, instead of scattered and diverse books which do little to examine the subject as a whole, an integrated, detailed, and highly cogent and coherent work has appeared.

A crucial high aspect of this volume is that it is able to look at the French Air Force for an extensive period of time, and while it is teleological in a certain extent in focusing on 1940, it is able to project a broader understanding of its problems and deficiencies than the normal work which principally focuses on the 1930s with some callbacks to 1920s experiences. Instead The Rise and Fall of the French Air Force show's its long obsession with the idea of twin-engined bombers capable of carrying out strategic bombing of Germany, alongside the limited focus which existed upon close air support, both on behalf of the French Air Force and on the army's side itself. Instead, it paints a convincing picture of an air force which was highly concerned about the idea of strategic bombing, and indeed had broad popular support and a mandate to focus on just such a role.

Production is also covered very well, showing the way in which the French tried to first build up their BCR (bomber - combat - reconnaissance) aircraft and the woes that they sustained with their strategic air force, and then the difficulties with their production in the run-up to 1940. Here, the book shows its ability to focus in on the gritty details on the ground, after previously covering the big picture of changes in French doctrine and ideas of how the war would be fought. This is matched by its important understanding of the technical changes and technological development present in the creation of the French bomber and above all else fighter force where the knowledge on the part of the author enables him to clearly show the ways in which French aircraft development progressed, with the progress and pitfalls.

When actual war arrives, the book continues to impress, with excellent details of the fighting in the air and its relationship to the ground, support services, the decisions undertaken for how aircraft would be used, and what the problems and missed chances of the French were. It strikes an excellent balance between hypothetical discussion of what the French could have done, and the unfortunate reality of what actually happened. Indeed, throughout the book there is a constantly well done mixture of optimism and scathing critique as necessitated, providing a history which fairly and honestly evaluates the triumphs and problems of the French air force;

For anybody interested in understanding general French air force strategy, aircraft design, operations, production, and general doctrine in the Battle of France and the Interwar period, and even to some extent the First World War, this book is without doubt the best on the subject.

© 2019 Ryan Thomas