The Six Greatest of All Arts: Architecture

ARCHITECTURE, the King of Form, Function and Perspective

Of all the arts, architecture is the only one that enjoys a continuum of perspective that is unbroken and fluidity of form that is complete. In other words, it is only possible to achieve a three-dimensional figure in architecture. In other arts, like painting, ‘linear perspective’(renaissance connection.org, 2015), a solution where distant objects converge into a line that resolves into a horizon, becomes the closest a flat picture frame or canvas of a Brunelleschi painting can convert into 3-D. According to Leon Batista(1956), making a work of art look bodily transforming to the user requires actual mathematical measurements such that the foreground contains the main objects of the subject, while the background, recedes linearly into a horizon that is about the ‘square’ of the height of the person who views the picture.

With the above background to act as a hint of an an explanation as to why architecture is one of the supreme arts in form and perspective, this treatise on the art will first compare it with the other major arts with regard to form and then delve deep into the apologia for the greatness of the art of building.

Mimicking In Film

Smith(2011) claims that despite the hullabaloo about the coherence of the whole in a motion picture, actually, this very continuity is a disparagement or break of the plot of the picture, physically speaking, because it leads to a ‘discontinuity’ between one shot and another that replaces it. In theory, the eye’s blink is enough to be a cheating way for the film editor to make the viewer move effortlessly from one clip to another without seeing any break, but for a virtuoso, it is clear that a motion picture is made up of many stills, each of which enforces itself to the next to create movement. In short, in film, like in painting, the search for form and perspective comes in form of a clever fusion to produce a ‘smooth’ (Smith, 2011) transition from one shot into the follow-up.

Imitation In Books

A novel also lacks physical form from one chapter to another. This is why some books ,especially of the modernist fictional periods, between 1900 and 1950, primarily Samuel Beckett’s trilogies have no conventional breakup between pages. However, the chapter has always been an essential factor for marking the passage of time and creating suspenseful breaks between one important action into another. However, as Dames(2014) recounts, Thomas Mann, when penning his masterpiece, Magic Mountain did not view chapters as aesthetically all that needful for he claimed that history never produces something physical when one year is fusing into a new one: only people who live on their earth practice frugal means of marking the passage of time by creating jigs or lighting fireworks. As such, a chapter may be the closest that a novel uses, at best, to mark the momentary pause a viewer of a building (thinking of architecture) has, before moving to the next side to see the whole, for one cannot view the entire building at once: one facade at a time.

Form in Classical Music

The clearest way to mark the passage of time, or feel form in the classics is, for the common listener, to hear the momentary, jagged poise of a player’s fingers rearing to move on to the next chord while the present one is mournfully ending its run, and it has impregnated the air with its melodic sweep.

Conception in Rock Music

Like other humanities that try to imitate the unapproachable perfection of form in architecture, rock music comes up to its own clever, albeit, hard rescue with the use of concept albums (jkornfield.net, 2015). The idea is that the use of a unifying theme, harmonious instrumentation or similarity of other elements will act as a basis of what one may call continuity for lack of any other word that can find a mean for what one calls form in architectural terms. When the Beatles were recording the influential Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, there was one key that ended the initial title song before keying in the next one in a mildly similar tone and so forth so that the entire album seems like under one umbrella. There is also another device disc jockeys use to achieve harmony, which is a rather not quite successful one: fading in one tune into another.

After that classification of form on a comparative basis, below is a further dissection of the elements that make architecture more than just a discipline holding on its grip onto terra firma.

The History of Periods in Architecture: A Brief Perspective

There are roughly fourteen phases of architectural history right form the creating of Stonehenge in Roman Britain, through the Renaissance, Rococo,Baroque and postmodern times. All of these periods produced distinctive merits that would rival major arts like painting and, currently, design.

Perhaps more than any other art, architecture is capable of flourishing into greatness with the most rudimentary of tools available. Some of the masterpieces of the world, and actually the seven wonders of the world, include nearly everything architectural, one of which being the Pyramids of Giza whose period was from three millennia to 900 years before Christ. Their major merit was the largeness, linear form and also the ‘engineering’(about.com, 2015) process that easily, if not exceeds, from a relative time-continuum point of view, inspires modern skyscrapers.

Byzantine art also flourished at a time when other humanities were at a lull. When King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table were the only tales that books could afford, architecture, through emperor Constantine was making buildings, elegant, beautiful and mosaic, and apparently, discovered the famed domed roof. The period was between 527 to 565 AD.

It was not until the Romanesque period came, three hundred years later that the Middle Ages gave the world the gift of church beauty, still apparent today. The introduction of the arch to enunciate the apparently low-lying crude structure would later merge with French architecture to bring the full stateliness of the Gothic period into being. St Peters Dome in Rome would borrow many elements like the Romanesque dome, the grace of the Gothic period and the mosaic of the Byzantine (in the interior, basically in paintings by Michelangelo) to climax architecture into one of its ripest periods, the Renaissance.

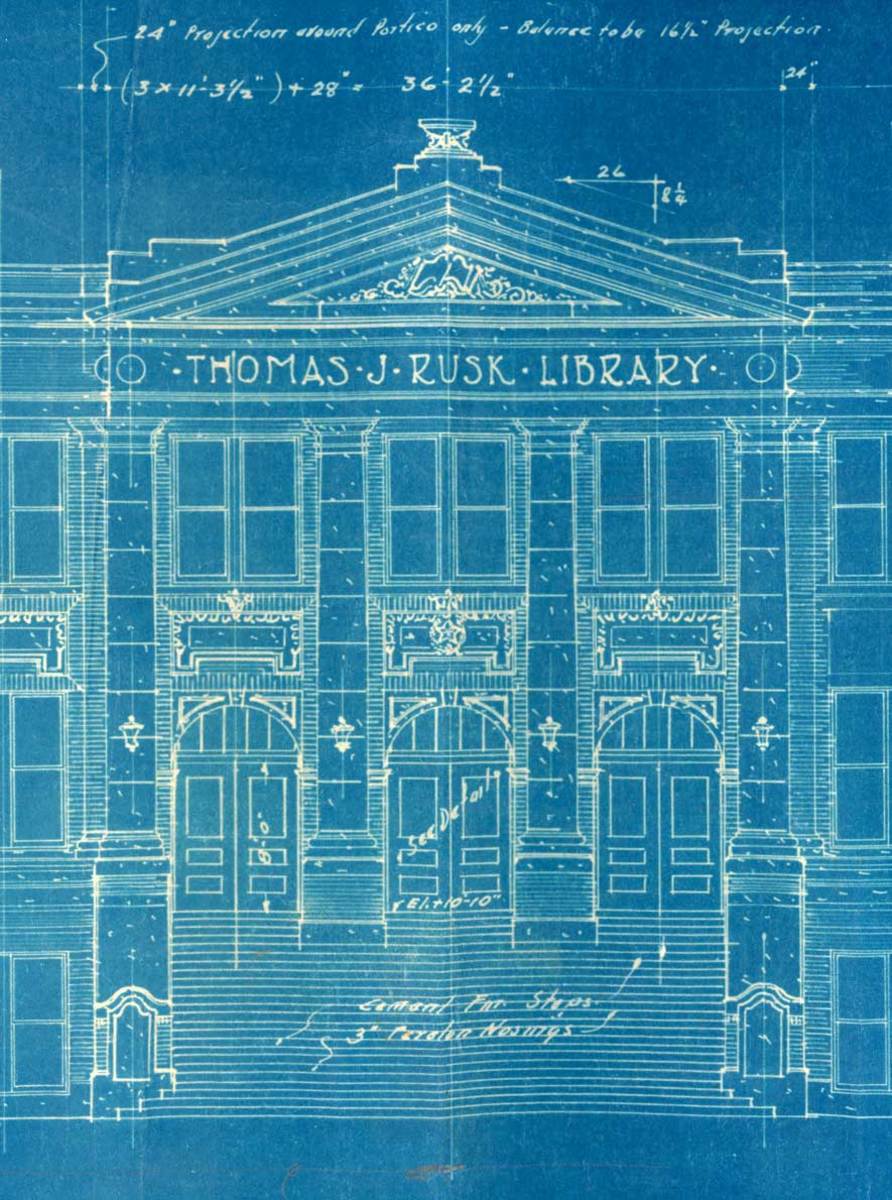

Some historians argue that perhaps architecture was as great as painting during the renaissance due to the various masterpieces from the period and later eras, like Baroque. In fact, over other arts, architecture has a grit of staying through centuries, each time epoch bringing a new element that contribute into making the work great some day. For instance, the world’s biggest museum, the Louvre in Paris, came into place as a colorful castle in the 13th century, transforming later in 1792 (during Baroque) into its present status as a cradle of historical artifacts. However, the transition that made it into a worthwhile museum came through an invocation by a king in 1546 (renaissance) from a recently converted mansion, into a revamped hub for artistic souls, especially painters, even as da Vinci’s La Gioconda became one of the holdings of the structure at this period.

Thus, as Dante was penning his Divine Comedy, Romanesque architecture was going up, and as Raphael was painting the School of Athens, the dome was having its heyday all over Europe, and ten years after the death of Shakespeare, Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome was undergoing its consecration, in 1626; as Milton’s Paradise Lost, was undergoing publication, Palace of Versailles was just about to enjoy its inaugural.

Secret of a Great Art: Post Modernism and Beyond

Since 1889, when the Eiffel Tower opened the skies of Europe and the rest of the world into tallness for all time, it was no secret that old linear forms that emphasized cheating arches to support rounded pillars and stairways echoing into infinity, of the graceful architecture of the past were gone. Nowadays, when one hears of the number one of anything, the beauty, daredevilry and tallness of skyscrapers comes into mind. Functionalism in the statuesque, no-nonsense, intimidating, plain block buildings is all one sees today. With Rand(2005), in her novel The Fountainhead, it was make or break for her hero who defied a banking community in New York City into not believing that banks need be low-lying and house-like to attract customers. Indeed, nowadays, blue skyscrapers of bank establishments have made the apologia of the above novel become all the rage and no one questions the morality of that any longer.

Summary

The fact that linear perspective is the way paintings cheat their way into the graceful form of architecture, whereas flashes of light are how acts in a concert hall mark the passage of form in a piece of ballet, and the fact that a masterpiece such as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony has four movements, and that concepts albums all have key intonations to transfer one song into another is no mere footfall: it is the celebration of form, the leading element in architecture. This is why it is inexcusably one of the greatest of all arts, and not just because, according to Ludwig(1995) ‘30%”s’ of the greatest architects earned repute compared to ‘40%’ in music, but because architecture is all before one’ eyes to see.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might also wish to read three other writings that preceded architecture in this series on the six greatest of all arts:

This is even as we move on to the penultimate part of this series, rock music, next.

References

Ludwig, A. M. (1995), The Price of greatness: resolving the creativity and madness controversy.’Guilford Press, NY. Print

Discovering Linear Perspective, (2015).From http://www.renaissanceconnection.org/lesson_art_perspective.html

Smith T. J., (2011) The Attentional Theory of Cinematic Continuity, Birbeck, University of London, London. ,

Listening to Classic Rock Music Achievements in Album Continuity From: http://www.jkornfeld.net/rock_music_concept_album.pdf

Dames N. (2014) The Chapter: A History, New Yorker. Retrieved from : http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/chapter-history

Craven J., (2015) Architecture Timeline: Historic Periods and Styles, Retrieved from: http://architecture.about.com/cs/historicperiods/a/timeline.htm

Rand, The Fountainhead, 2005 (Penguin Books.