- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- American Literature

The Women of The Great Gatsby

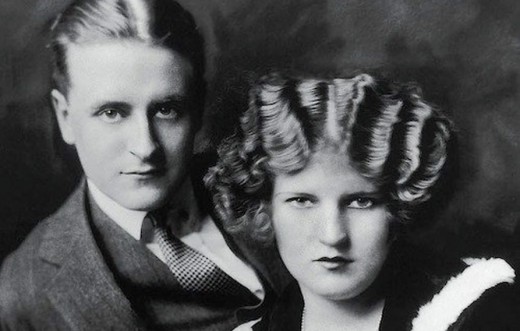

F. Scott & Zelda

Modernism rose after the events of World War I. With it came what was seen as the first real advances in feminism. Woman’s suffrage was making strides; it’s most pronounced accomplishment of the time was the adoption of the 19th Amendment, giving woman the right to actively participate in the governing of the country. Women were more educated and aware than they had been before. Yet, it also showed them how much they were held down and how much further their struggle was. They were able to “both understand active subject status and desire it …able to recognize their own exclusion from the privileges of full subjectivity in the patriarchal world. With all their decisions made for them, and nowhere to use their well-developed intellects, they stare blankly at the horizon…by society’s lack of good career options…and its general rejection of feminine self-assertion” (Gregory 780).

Though men are the focus of the novel, there is much to assess from the women of the time, especially seen through the lens of the male perspective. The woman of the novel are shown to have modernism traits, but still possess old values. It is then that the woman of The Great Gatsby, like other modernist works of fiction, are juxtaposed between their modernist feminism and the misogynistic view of the author.

Why did men who were so willing to look at other aspects of life and art in a different way, challenging the status quo of the bourgeoisie, still clinging to long accepted views of women? Frances Kerr feels that “One of the fears…was that popular culture, dominated by women, was fast becoming the major form of artistic expression in the modern world, appropriating the audience and diminishing the market for serious art” (413) and this view is “attributed to many major male modernist writers,” (413) Fitzgerald among them. For all their education and advances, women were still seen as not being able to fully appreciate art on an intellectual level, instead opting for anything more commercial. This, of course, was not true as women then were not only capable of appreciating but also creating literature, as seen with the works of Kate Chopin, Zora Neale Hurston, and Fitzgerald’s fellow expatriate Gertrude Stein.

Part of the take on the female characters had to do with the women in his life at the time. The first was Ginevra King, “a wealthy Chicago debutante whose initial acceptance of Fitzgerald was a supreme social triumph; her later rejection of him became one of the most devastating blows of his life” due to being “’thrown over’ in favor of an acceptable suitor with money and social position” (Mangum). It was after this disastrous affair that he was to meet Zelda Sayre, his eventual wife. At the time, “he was stationed near Montgomery, Alabama …although willing to become engaged to Fitzgerald, did not finally agree to marry him until he could demonstrate his ability to support her” (Mangum). There can be seen in these two women parallels in the character of Daisy Fay Buchanan.

Daisy does have a brief fling with Jay Gatsby before the war. As he informs Nick, he “took what he could get, ravenously and unscrupulously” (Fitzgerald 149). In their affair, there is a sexual freedom that does not require a commitment. He is poor, but very much in love as is she. The color green here for Fitzgerald is “a recurrent symbol of hope, and money…the profoundly symbolic green light at the end of the Buchanan’s dock” (Koch 158). Daisy is represented in the story for Gatsby, before they meet again, by the light of her dock. She is the reason he becomes so determined to become an obscenely wealthy as he does; he is led to believe he has a chance to win this girl who would have been out of his league. Daisy is fighting the norms of society with her anti-Victorian attitudes towards sex, as well as even considering a relationship that would be viewed below one’s status. She is even the inspiration for Gatsby to dare to step out beyond his station.

Daisy is a woman who has money and influence, but still is trapped by the need to be with a man that is viewed, at least to the outside world, as respected and worthy. This is was she finds in Tom Buchanan. She is rumored to have dispute with her parents over wanting to see Gatsby before he ships off, but it is put down quickly and she is engaged to Tom within the year (Fitzgerald 75). She does express a brief moment of doubt, as the reader sees when Jordan tells Nick about night of the bridal dinner. Daisy, drunk and heartbroken, is seen clutching a letter, assumed from Gatsby, and ready to call off the wedding. Yet, by the wedding day, she is fine and doesn’t look back (76). Then, when she is reunited with Jay, she is set to run off with him. Being presented with the truth, he is not from old or legitimate money, she once again chooses the prestige over her feelings (132-133). She was presented twice with the choice; she made the safe choice as women of her station have before her.

A woman who also has a choice is Myrtle Wilson. She has the choice to marry George Wilson, despite her protest that “I married him because I thought he was a gentleman…I thought he knew something about breeding” (Fitzgerald 34). She also has the choice to go or not go with Tom Buchanan when she meets him on the train (36). Myrtle is woman who wants to be more than what she is, and to get that, she sees her way of achievement in Tom Buchanan. She is not content to remain in an economic status that society deemed for her from birth. The marriage and affair are her moves, though both fail in the end, to obtain a better life than what she could have hoped for.

The problem for Myrtle is that’s not the way Tom sees things. She is just another one of his possessions. He has no intentions of leaving Daisy, but he makes up the lie that he cannot get a divorce because his wife is Catholic to string Myrtle along and keep her (Fitzgerald 33). When she even dares to mention his wife’s name, he hits her (37). Then later, when she is killed, his first thought is to distance himself from Gatsby’s car (140). Later, he uses her death to help rid himself of his wife’s romantic rival, something he practically admits to Nick (178). She is an object, like his home and his car. Just one more thing that his wealth can afford him. He does not love or respect her as a person. Her ambition just does not allow her to see it.

Unlike Daisy and Myrtle, Jordan is the only truly independent woman in the whole novel. She has a career and is not dependent on a man for her lifestyle. “Jordan is, literally and metaphorically, a woman successfully playing a man's game: her professional golfing career makes her self-sufficient, allowing her to live and travel independently” (Froehlich) But for this, she is not viewed in a favorable light.

When Nick first meets her, he is struck by the fact that he recognizes but can’t place her. When he does, he informs the reader “I had heard some story of her too, a critical, unpleasant story” (Fitzgerald 18). Here is a woman who is making it in the world on her own, even playing professionally what is considered a man’s sport. Yet, the prevailing thought is that she cannot achieve this in an honest manner. Whether she actually did commit the infraction is not the issue; the fact that the accusation is out there, and more than likely started with male encouragement, is enough. It is easily believed and not questioned.

Fitzgerald was known to blame part of the lack of initial success on The Great Gatsby on women; he acknowledged it probably would have sold better if it wasn’t so male centric. Yet, it is in his acknowledgement that he shows readers then and now the problem with modernist female. She is suddenly thrown into a world where she has freedoms and privileges not had by former generations of the gender, while still subject to a patriarchic society not ready for the change. Fitzgerald, through the women in his greatest work, shows the readers this conflict of not being able to reconcile the modernist female in their own minds.

Works Cited

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. Scribner. New York: Scribner, 2004. 1-180. Print.

Froehlich, Maggie Gordon1. "Jordan Baker, Gender Dissent, And Homosexual Passing In The Great Gatsby." Space Between: Literature & Culture, 1914-1945 6.1 (2010): 81-103. Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 20 Nov. 2014.

Gregory, E. "Modernism, Feminism And The Culture Of Boredom." Modernism-Modernity 20.4 (n.d.): 779-782. Arts & Humanities Citation Index. Web. 22 Nov. 2014.

Kerr, Frances. "Feeling `Half Feminine': Modernism And The Politics Of Emotion In The Great Gatsby." American Literature 68.2 (1996): 405. Academic Search Premier. Web. 20 Nov. 2014.

Koch, Matthew. "Wealth And Women: The Expatriate Performance Of Affluence." Interactions: Ege Journal Of British And American Studies/Ege İngiliz Ve Amerikan İncelemeleri Dergisi 23.1-2 (2014): 145-160. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 20 Nov. 2014.

Mangum, Bryant. "F. Scott Fitzgerald." Critical Survey Of Long Fiction, Fourth Edition (2010): 1-11. MagillOnLiterature Plus. Web. 22 Nov. 2014.

© 2017 Kristen Willms