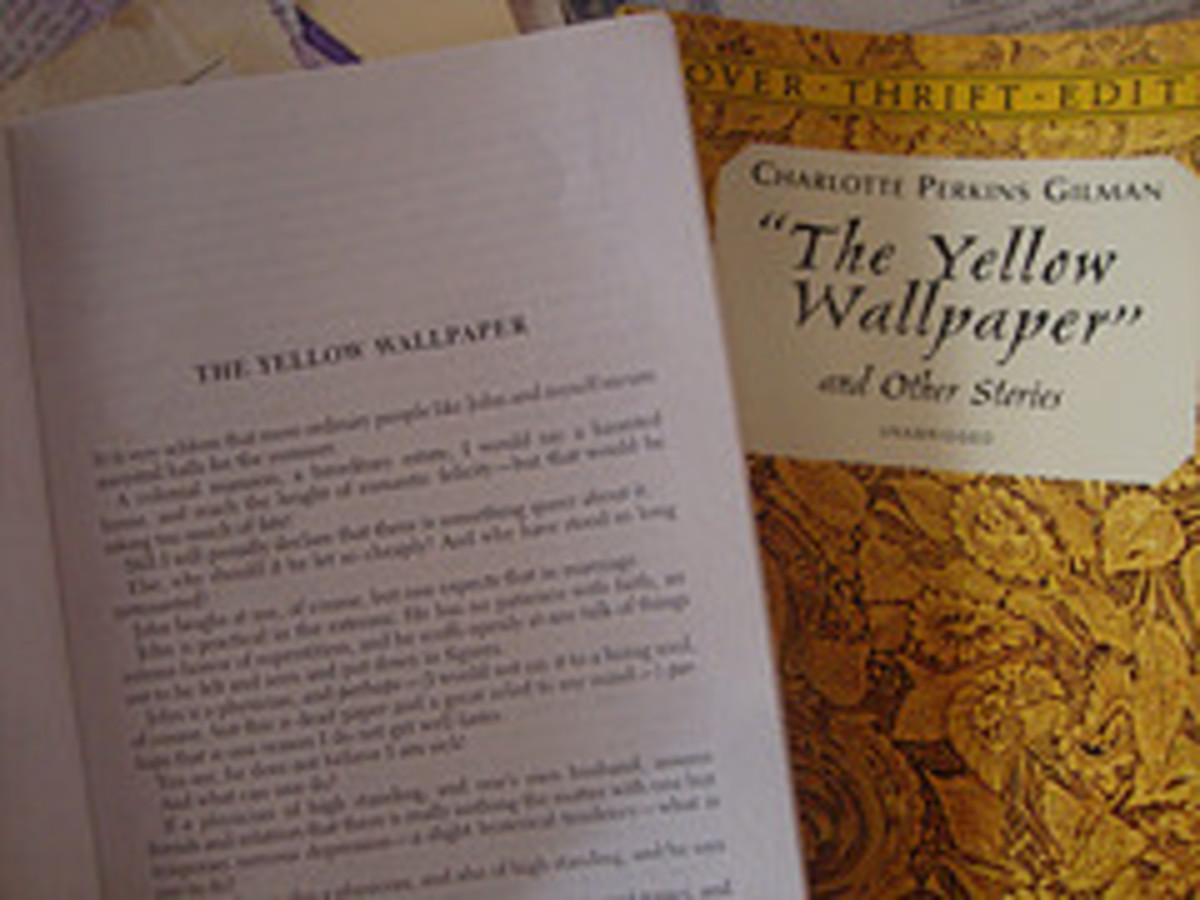

“The Yellow Wall-Paper”: A Riposte to Social Patriarchy

“I cry at nothing, and cry most of the time”

– Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “The Yellow Wall-Paper”

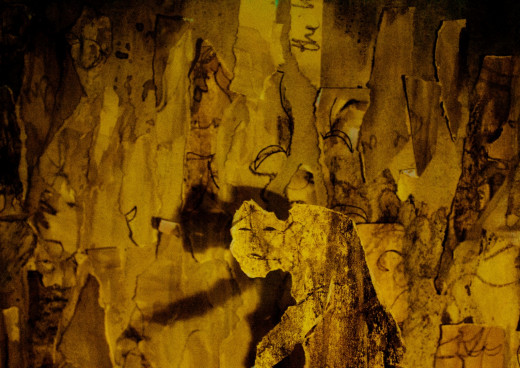

If you examine literary history, it is the same story. It all refers back to man to his torment, his desire to be at the origin; back to the Father. There is an intrinsic bond between the philosophical and the literary (to the extent that it signifies, literature is commanded by the philosophical) and phallocentrism (Kourany, Sterba, and Tong, pg. 367). The philosophical constructs itself starting with the abasement of a woman. Subordination of the feminine to the masculine order appears to be the functioning of the logocentric and phallocentric machine: patriarchy. For Sigmund Freud (1896) — the Austrian Psychologist whose works pioneered the development psychoanalytic theory and criticism, and who’s influence is undefinably extensive—the fatality of the feminine situation is a result of an anatomical defectiveness (Kourany, Streba, and Tong, pg. 368). Furthermore, Freud believed that there is only one libido and its essence is male. Thus, one of the leading psychological and philosophical figures at the fin de siècle was a heavy supporter and advocate of the existing patriarchal social structures manipulating the domestic scenes in every-day public and private life, which ultimately, and immorally, empower the masculine and marginalize the feminine. As Karl Marx voiced that the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle, so too, as Charlotte Perkins Gilman argues in her masterful short story, “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” that the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of gender struggles.

Otherness

The Modernist philosopher Frantz Fanon argued that “For the black man, there is only one destiny and its white” based on the premises that ideal spectacles of society (whiteness) contradicted the spectacle of the Other (blackness), which left the Other no choices but to assume the ideals of superiority and reject their otherness (Buckingham et al., pg. 300). Following along Fanon’s premises, the tension between femininity and masculinity fits the same theoretical model; femininity, characterized by empathy and an appeal to pathos, is labeled with Otherness because it is contradictory to masculinity, which is dominated by practicality and an appeal to logos, thus leaving woman no choice but to abandon their dignity and self-empowerment and succumb to social pressures of patriarchy. Gilman expresses this binary opposition between genders in her story by establishing a literary foil between John and the female speaker. For instance, John, the speaker’s husband, is characterized with an almost autistic temperament, meaning extremely male-brained, and logocentric: “He has no patience with faith, an intense horror of superstition, and he scoffs openly at any talk of things not to be felt or seen and put down in figures” (Franklin et al., pg. 1684). Gilman’s feminine speaker, on the contrary, exhibits an unwavering tendency to lean towards intuition and feelings: “I am afraid, but I don’t care—there is something strange about this house—I can feel it” (Franklin et al., pg. 1685).

Notes

[1] Most of those who have written about human nature have been men and they have taken maleness as the standard against which they judge human nature. Furthermore, men have defined women by how they differ from this standard. Thus, “man is defined as a human-being and woman as a female” in regard to all political, social, moral, and physical philosophies (Buckingham et al., pg. 276).

Gender Roles

Awareness of this marginalizing distinction, as the Modernist French Philosopher Simone De Beauvoir described it as “Man defined as a human-being and woman as a female,[1]” allows readers to further detect the direct and indirect struggles between the sexes, and the struggle between woman and her environment in Gilman’s “The Yellow Wall-Paper.” Focusing on the former, Gilman’s speaker and her husband often reach high points of tension because of their extreme differences in thought process. For instance, when the speaker says “I am afraid, but I don’t care—there is something strange about this house—I can feel it” and her husband rationalizes her emotions by telling her “What I felt was a draught, and shut the window” (Franklin et al., pg. 1685). Another instance in Gilman’s story that highlights this battle between the sexes directly is when the speaker says “And yet I cannot be with him, it makes me so nervous. I suppose John never was nervous in his life. He laughs at me so about this wall-paper!” (Franklin et al., pg. 1686).

Self-Perceptions and Gender

Resulting from these direct conflicts between masculinity and femininity outlined above, Gilman’s speaker feels compelled to reject her intuition in the direction of subjecting herself to patriarchy and therefore passively assuming the ideals of superiority and ultimately rejecting her otherness. For instance, she denounces her own repressed situation by saying “John does not know how much I really suffer. He knows there is no reason to suffer, and that satisfies him.” Furthermore, she rejects her feminine tendency towards intuition by saying “I ought to use my good will and good sense to check the tendency. So I try.” Lastly, she even rejects her own appeal to pathos by saying “I cry at nothing, and cry most of the time… and I did not make a very good case of for myself, for I was crying before I had finished” (Franklin et al., pg. 1686-1689). Here, Gilman’s speaker is blatantly dwelling in self-doubt and experiencing an inferiority complex, which ultimately compels her to define and redefine herself according to the ideals of her masculine environment.

Concluding Thoughts

Even though Gilman’s speaker portrays the repression of femininity, "The Yellow Wall-Paper" is nevertheless a feminist riposte to the trusts and shots of deflating sarcasm, taunts and marginalizing insults aimed at women on a day-to-day basis. Her prose shows the masculinity (logocentric, manipulative, and controlling) of the inner-machinations of society; and how the masculine role mocks these subliminal curtains shrouding the injustice and irrationality of patriarchy; pretending that these injustices are nonexistent. Furthermore, Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper" captures the woman's struggle to overcome subordination and achieve her own autonomy and equality (and thereby freeing themselves from the bondage and freeing men from the distortions that come from dominance) in a period characterized by democratic hegemony (Foner, Garraty, 1991). Thus, as a premeditative display of postmodernity, Gilman effectively fragments, fractures, and adds her voice to the heteroglossic pool of plurality against patriarchy, which becomes an important characteristic of the act of literary liberation from marginalizing structures of society, discriminating traditions, and short-sighted ideological systems in the 20th century.

References

Buckingham, W., Burnham, D., Hill, C., King, P., Marenbon, J., Weeks, M. (2011). In The philosophy book: Big ideas simply explained (1 ed., pp. 198, 276, 300-301). New York, NY: DK Publishing

Foner, E., Garraty, J. (1991). The reader’s companion to american history. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Franklin et al. (2008). The norton anthology of american literature. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Kourany, J., Sterba, J., and Tong, R. (1992). Feminist philosophies. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.