We are no longer in France: Communists in Colonial Algeria Review

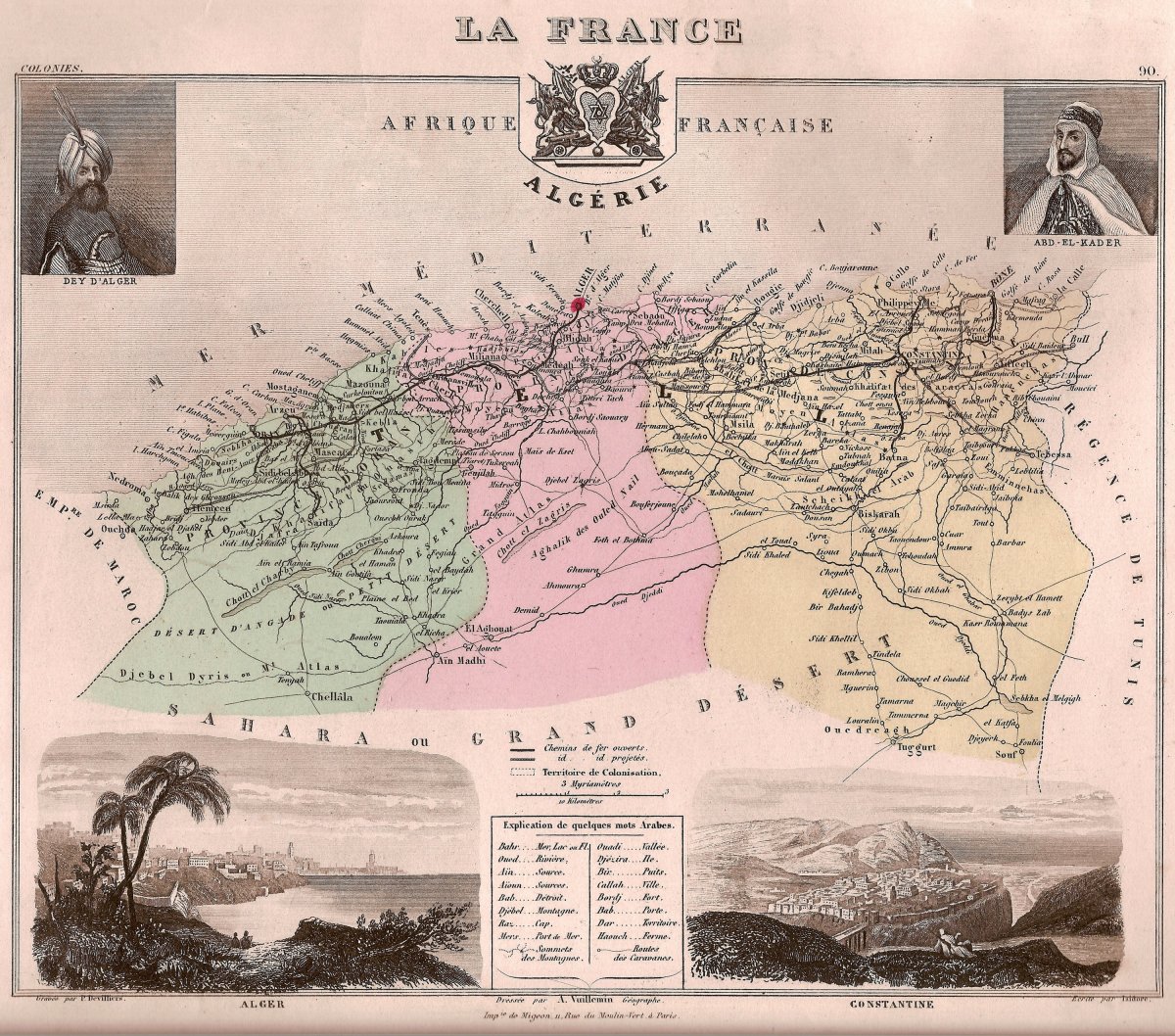

Algeria, conquered by the French in the years following 1830, had a strange history under France: eventually administratively absorbed into France, at the same time it clearly continued to exist as a colony and as a foreign territory in much of popular perception, and was de facto governed by markedly different rules than the rest of the nation - with a vast population of native Algerian Arabs and Berbers ruled over by a small but not insignificant European minority that was around 10% of the population, and which unlike the former enjoyed rights as full French citizens. In addition to bringing colonialism, the Europeans also brought European ideas, and one of these was communism. This story is the history of communism in French Algeria, this strange region formally part of France and de-facto alien, the saga laid out in We are no longer in France: Communists in Colonial Algeria by Allison Drew.

An introduction, "Imagining socialism and communism in Algeria", functions to lay out the existence of Communism in Algeria, that like South Africa it was unique in Africa due to its mixture of a large European settler population and natives, and to provide for the general organization of the book.

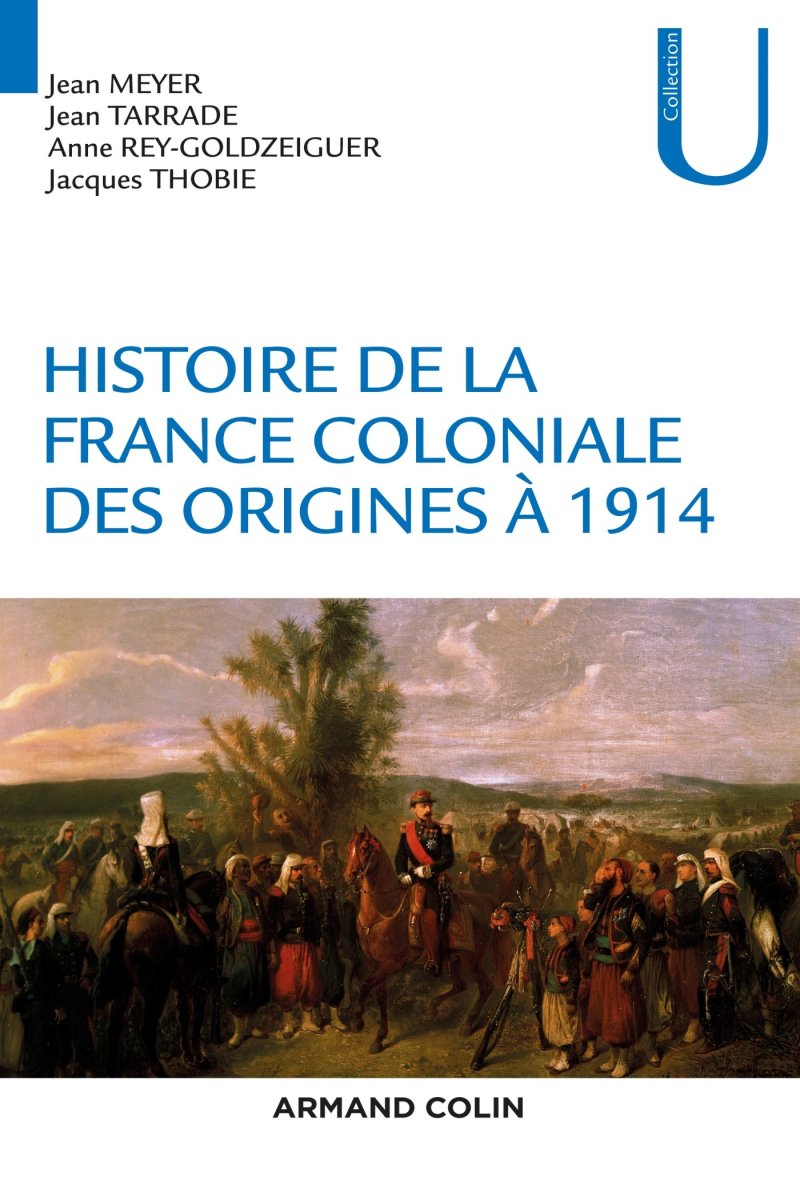

The first chapter, "The Land and its Conquest" is devoted to a history of the French colonization of Algeria and the class structures which were created, and French instruments of oppression and the hardships faced by the Algerian population, above all else the French theft of Algerian land.

The second chapter "Grapling for a Communist foothold", discusses some of the tactics, doctrine, and evolution of the Communist party during the 1920s. However, it did hit upon the idea of prison strikes and opposition to French repression in Algeria, which proved an effective tool and the root of its later success.

In the third chapter introduces the mass action which was undertaken by the communits, in ‘The mountain “was going communist”’: peasant struggles on the Mitidja", which rescued the Algerian Communist Party from its catastrophic low point with an alliance with peasants to resist French land expropriation. Although it was brief and they continued to focus on city organizing, the importance of unity between the city, the countryside, and mountain strongholds is one which would prove decisive in the Algerian war of independence.

Following this is the 4th chapter, "'This land is not for sale': communists, nationalists and the population front'", dedicated to activities under the Popular Front, where the need for action against fascism in line with the Parti communist français and directives from Moscow pushed the Algerian Communist Party to take up a line stressing the anti-fascist struggle much more than the anti-colonialist struggle. This led to it effectively becoming divorced from a popular opinion that was becoming increasingly nationalist.

During the 5th chapter, entitled "The nation in formation: communists and nationalists during the Second World War", this policy went through dramatic evolutions, as initially the PCA (parti communist algérien, or Algerian Communist Party) supported anti-colonial activity and suddenly reversed itself upon the question of fascism, as the Soviet Union cooperated with Germany following the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. However, this itself was then reversed following the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany, whereupon the Communists did their best to fight against fascism and returned to their earlier positions. Consistently, the French government, under both the late IIIrd Republic and Vichy, did its best to repress them, but following the liberation of North Africa in Operation Torch, the communists were able to resume their activity. Although they exited the war appearing to have profited from it in numbers and organization, in fact they had become markedly estranged from the nationalist sentiment of public affairs.

The 6th chapter, 'For an Algerian national front: unity and division in the liberation struggle", continues this story in the post-war era, where the PCA gradually over time migrated to a position advocating Algerian independence but continually focusing on a democratic and pluralistic view of Algeria. It gradually became more and more Algerianized, reflected in its administration, and it did grow in numbers, but its early electoral successes in the post-war elections had been rapidly lost.

For the 7th chapter, "Sparking an insurrection: pressure from the countryside", the Algerian Communist Party faced the problem of how to confront the civil war in Algeria. When this begin, in 1954, it was caught by surprise and was initially uninvolved. In time, it came to support the FNL and its struggle for independence in Algeria, but cooperation between itself and the nationalist organization had the effect of sidelining it, and the FLN never really accepted it and continued to be prejudiced against it. The PCA also faced French reprisals and repression which hurt its own capacities.

"'Our people will overcome': to the cities and prisons", as the 8th chapter, changes the scene to focus on imprisoned communists and some of their activities in the prisons of French Algeria, where they worked on things such as exposing torture and demonstrated once more their unique status in being mixed between Europeans and Algerian. It also focuses upon providing a general overview of the war, key intellectual figures such as Franz Fanon, and some of the external contacts of the PCA.

In the 9th chapter, "'We need a country that talks': Imagining the future Algeria", focus is placed on the ending negotiations of the Algerian Civil War, debate over tactics, and above all else the party programme for post-independence Algeria, which focused on the creation of a pluralistic, progressive, democratic nation, one which was in contrast to the Front de libération nationale's one party state ideal, which would lead to later conflicts.

The conclusion, "Algerian communists and the new Algeria", covers the temporary post-war success of the PCA, followed shortly by the banning of the communist party, the conditions of life in immediate post-war Algeria, and the political evolution following independence.

The key and sustained element which this book reveals is the attitude of the Algerian Communist Party towards the idea of the Algerian nation, an attitude which changed over time in response to international affairs, direction from above, and its own changing nature. The Algerian Communist Party started out closely aligned to the French Communist Party but was increasingly drawn towards an anti-colonial view, which was it must be noted, nuanced by the need for anti-fascist political activity in the run up to, and during most of, the Second World War. This is well demonstrated in the book, which shows the wide array of reversals and changes in the position of the PCA.

It is also excellent at demonstrating the changing nature of the composition of the Algerian Communists, and the way in which this composition changed over time. Through a careful examination of archives and material the members of the PCA have been shown in depth, with the evolution of the party to become more and more Algerian and less and less European over time clearly shown. So too, the fact that it nevertheless remained unique in being a true mixed party which incorporated both Algerians and French.

One can certainly admire the amount of research that went into this project but at the same time it is clear that towards the end the amount of available material must have been somewhat limited for the author, for it begins to become somewhat thin for her, focusing on the general and rather well known story of the Algerian war with the Communists seemingly tacked on as an additional element. By contrast, the section which to me seems to be the best well researched and cohesive is that of the Interwar period, when it covers in superb detail the broad objectives and changing policy of the Algerian Communist Party, as well as its actual actions on the ground with the mobilization of peasants against French land theft. This, as the book makes clear, was a vital element for later activity during the Civil War - but ultimately the red maquis were decimated and it seems that the Communists and their role was limited. In fact, this is another area where there could be more note: how big actually was the influence and role of the Algerian Communists during the Civil War, as a whole?

The most appealing element of all which is present about this book is that there is very little in the way of alternative material which is available concerning the Algerian Communist Party and Algerian Communism, with most works focusing either on the French Communist Party or at most upon the relationship between the Algerian Communist Party and the French Communist Party. This makes the focus which is expressed here upon the Algerian Communist Party itself and its own realities, objectives, policies, practices, and politics one which is fairly unique. Even if the relative lack of information on the Communists during the Civil War era is to be regretted, the generally high quality of available information throughout the rest, with wise comparisons to South Africa's situation and an impressive multi-national research effort, both social and political history, and effective historisation and a consistent historical line, combine to make it an exceedingly interesting and useful book to learn about a largely forgotten aspect of the Algerian War.

© 2019 Ryan Thomas