- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Commercial & Creative Writing»

- Creative Writing

Western Short Story - Father Rivera

Father Rivera

They left me to die.

I was on my way to Tucson to meet a cattle buyer when I ran on to them. Most of the Apaches were at peace and on the reservation, but there were a few bands of young bloods wearing paint and looking for glory, so I was glad for the company. Three well armed men might give renegades pause, and I was a man traveling alone. They were out of work cowhands, or so they claimed.

Tom Dawson was a big, silent man with small, shifty eyes, while Charlie Gibbs wore a good natured grin, and had a gift of gab to go with it. I noted that their horses and outfits were a little too good for cowhand wages, but I quickly dismissed it as unimportant. It was late June and the monsoon storms were building to the south.

When Gibbs wasn’t talking, he was singing, and he had a fair voice. My own voice would scare a cat, but I compensated for that by being loud. Gibb’s occasionally glanced sideways at my caterwauling, but I just got louder, so he shrugged and kept on riding.

We camped near a spring I knew, and after making a supper, Tom Dawson offered to take the first watch. Charlie Gibbs would take second watch, and I would stand for the last watch. Dawson climbed the knoll, and Charlie broke out his mouth organ and began to play. I settled in my blankets and drifted off to the soft notes.

I awoke to broad daylight, with a splitting headache and found by myself tied ankle to wrist with rope. I struggled to sit up and found myself alone, bound, and stark naked, except for my socks. Tom Dawson and Charlie Gibbs were nowhere in sight. The side of my skull pounded, and I could feel sticky blood on my neck and shoulder. Evidently, I’d been clubbed in my sleep, stripped, bound, and left for the vultures. Gone were my horse, my gear, and the five thousand in gold hidden in my saddlebags.

I worked at my bindings for over an hour, but the knots were solid. At last, I rested for a few minutes and began looking around. Not seeing what I wanted, I rolled a few feet and began looking again. I did this several times before I spotted the shard of flint I was seeking. I found a crack in a rock, jammed the flint in it, and went to work sawing at the ropes. Half an hour later, I was free.

They had cleaned me out. Even my boots were gone. I walked to the spring and located the quart whiskey bottle I had noticed the night before. Some cowhand had discarded it long ago, and now, it might be the difference between life and death. I spent a few minutes looking for another, but no luck. I returned to the spring and filled my bottle first, just in case. I found a short mesquite stick to use as a stopper, and then I took a long drink from the spring. I waited for half an hour, and took another long drink. While I waited, I wove a crude hat out of grasses. A man without a hat would cook his brain under the summer sun, and I had little enough brain as it was. I took one more long drink, slapped on my grass hat, and set off. In the distance was the faded blue shape of Mount Lemon, and the small pueblo of Tucson lay at its base. I set my sights on it and took the first step.

By that afternoon, my socks were worn through, and my feet were raw and bleeding. My quart of water was long gone, but I carried the empty bottle. The next water was still ten miles away, and after that, fifteen miles to the next. Then the final twenty five miles to Tucson, so that discarded bottle could become the difference between life and death. Even then, I probably would not make it.

My formerly brisk walk had slowed to the relentless plodding of a tired, but determined man. My exposed skin was raw and blistered, and what I could see of it was cherry red. The only thing that hurt worse was my bare feet. When I checked my back trail, I could see my own bloody footprints. I bowed my head and kept on, almost missing that wagon.

The top of a wooden bow barely showed above the bank of a wash, and my dulled mind took a moment to realize what it was. I walked to the edge and looked down at the remains of a covered wagon. Some of the canvas was still in place, so I scrambled down the bank. I could use it to make a crude shirt and pants. I looked in the bed of the wagon, but it was empty. I was getting ready to tear up the canvas top when I noticed a metal topped, tool box fixed to the rear of the wagon. I pried open the latch and found a treasure.

Inside was an old pair of boots, with the heel missing from the right boot. Other than that, they were in good shape. They looked to be about the right size, so I removed the left heel and put them on. I also found a rusty knife, so I took that and put a quick edge on it using a flat rock for a stone.

I cut a serape, with a neck hole, out of the canvas and put it on. It scraped on my raw skin, but it would prevent further sun damage. I made sort of a skirt to cover my legs, and tied it with a strip of canvas. I dug further in the tool box and found a canteen, holed in two places by a bullet. But holes can be plugged, so I put the strap across my shoulders. Finding nothing else useful, I climbed the bank, and set off. My feet still hurt, but far less than before. I began to allow myself some hope that I might survive.

The tank at the bottom of the small mesa contained nothing but dust. The summer rains had failed to fill it. Water holes like this one were spotty at best, and the wise traveler did not count on them. I had no choice, and now I was looking death in the face. The Dead Horse tanks were fifteen miles away, and there was no promise of water there either. If they were dry, my fate was sealed.

I found a shaded spot and waited until dusk. There would be a full moon, and I would walk as long as I could see in the cool of the night. I set off after sunset and made perhaps five miles before the moon sipped behind monsoon clouds. I found a place to rest and drifted off, exhausted.

The following morning, it was still cloudy and cooler so I set off. Overhead, thunder rumbled, and I began to hope it would rain. If it did, I would use my makeshift serape to catch it and funnel it into my canteen and whiskey bottle.

I trudged on, my head bowed, and my mind on placing one foot in front of the other, so I didn’t notice at first that the wind was picking up out of the south. Then my grass hat flew off and as I grabbed it, I glanced over my shoulder and stopped in horror. To the south was a gigantic cloud rising nearly a mile above the valley floor and coming fast. It was a dust storm, and a big one, bearing down on me. There was no shelter anywhere nearby, so there was no choice but to keep moving.

A few minutes later, it caught me, and I lifted the neck of my serape to cover my mouth and nose the best I could. My eyes filled with dust and the tears rolled down my dusty cheeks. I kept moving, and the storm became more intense.

Suddenly, I realized I was no longer alone. In the gloom, I could make out several silent figures, standing on each side of my path. They were Indians, but their dress and paint was not familiar. Their faces were indistinct, and they seemed to shimmer in the blowing dust. I could not make out their eyes, but I could feel their steady gaze.

I must have been a sight, with my strange dress and hat, appearing out of a storm like that. I decided that there was nothing to do but keep on moving, so I lowered my head against the dust and walked on. I heard one of them say something, but it was a odd voice that sounded like the rustling of dry leaves, and there was a strange odor in the air of something musty and very old. I passed close to one of the figures, but his face was blurred, and I couldn’t make out his eyes. I was beginning to wonder if I was delirious when he reached out and pushed me sideways.

I staggered to my left a couple of steps and then resumed my shuffling walk. I heard a grunt in that same whispery voice, and I somehow knew it was a grunt of approval. I had passed a test. I kept on walking, and when I glanced over my shoulder, they were gone. I turned around and searched the blowing dust, but there was nothing. Who were they? Were they real? What did they want?

I walked another hundred yards before I found Tom Dawson and Charlie Gibbs. They were spread eagled on the ground, with their arms and legs pulled tight and spread almost to the breaking point. Both were covered with hundreds of burns, and their eyes and mouths were spread wide in pain and horror. Both were very dead and beyond caring.

It took a moment before I realized that there was something very amiss. They were both stretched out painfully, but there was nothing holding them. There was no rawhide binding their wrists and ankles and there were no stakes in the ground. There was also no evidence of a fire and no tracks. The dust storm might have partially covered tracks, but not all the way. There should have been tracks.

I shivered and looked behind me. There was no one. I walked on a few steps, and came to five small rocks, in the form of a ‘V’ which pointed left. Through the dust, I could make out an outcropping at the base of a small hill so I turned and walked that way, looking for shelter. I climbed behind a boulder, and there was a small tank full of clear water. It was an unknown water hole, at least to white men.

After drinking, I filled my canteen and whiskey bottle and sat back, waiting for the storm to ease. Exhaustion overcame me and I slept.

Two hours later, I woke and the storm was over. Getting to my feet, I looked back to where I had seen Dawson and Gibbs, and there they were, but this time they were surrounded by several, shadowy Indians, who stood there looking down on them. Then one raised his head and looked at me with his unseen eyes. He swung his arm and pointed at a small grove of mesquite trees, There, standing ground hitched, were Dawson’s and Gibb's horses. My horse was with them.

My gold was still in its hidden pocket, and each horse carried two canteens full of water. I rigged a lead rope, and mounted my horse, leading the other two and riding out from under the mesquite. The small band of Indians looked at me silently and the one who had pointed to the horses raised his arm to me. I raised my arm, and turned toward Tucson. A few moments later, I glanced back and all had disappeared, including the bodies of Dawson and Gibbs. Despite the heat, an involuntary shiver shook my body.

Two days later, with my business completed and my gold safely deposited, I was sharing a drink with the buyer. I hesitated and then told him my tale. A old Mexican gentleman at the next table turned and stared, his face pale.

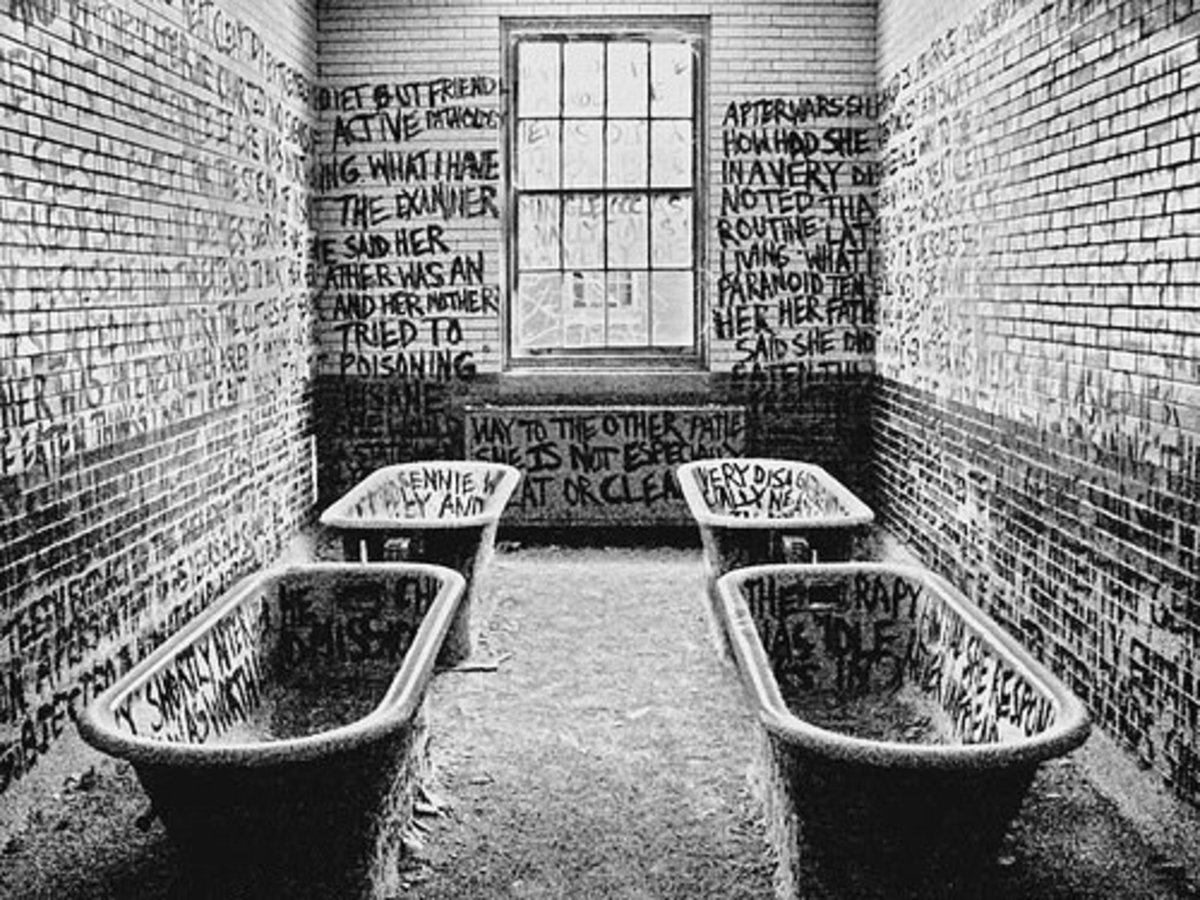

“They were the ones called the fantasmas, Senor…ancient ghosts! They were evil men, banned forever by the Great Spirit. You are lucky to be alive. They have killed many men. The only man they ever respected was Father Rivera, of the Old Spanish Mission…the one who wore the trapos...the rags, and a hat woven of grass.”