- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Commercial & Creative Writing»

- Creative Writing

Western Short Story - The T-J Connected War

War on the T-J Connected

I knew who it was as soon as I saw the cloud of dust off to the east. And I knew James would be riding with them. That foolish young pup thought those Brenton boys were someone to look up to, but all they were was Dentonville trash.

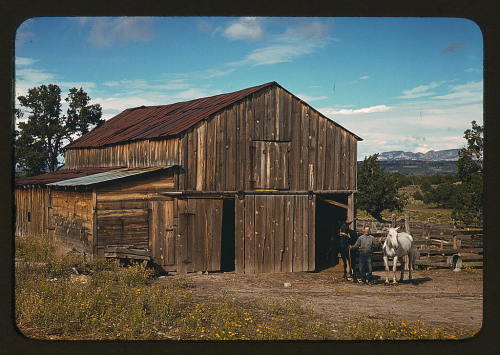

I looked over towards the barn and Tom was outside the big doors shading his eyes against the morning sun. He looked up, saw me standing on the porch and nodded. He disappeared back into the gloom of the barn where he had two Henry rifles hidden under the hay. He would be ready. Tom was steady as a rock. It was hard to believe Tom and James were brothers.

My father, big Tom Jackson, bought the two hundred acres where he built the house and barns and claimed another hundred thousand acres by right of possession and sheer will power. He dammed up four runoffs for water holes and developed three good springs. As a result, he had water when no one else did, but he shared it. He was a good neighbor, and people respected him.

He had fought off Indians, weather, and bandits. When rustlers ran off a small herd of cattle, he tracked them down and hung those who survived the gun battle. After that, wiser folks decided to leave the T-J Connected strictly alone.

When I was fourteen, a band of marauders left over from the war rode into the ranch yard and demanded horses and food from Pa. My brother George and I emptied three saddles from the hayloft and Ma blasted the leader with two loads of buckshot from the double-barreled Greener she kept by the stove. The rest wisely raised their hands and Pa fetched some rope from the barn. While he was shaping up a noose, he quietly suggested they might find Missouri more to their liking that time of year. They gathered up their dead and left out of there in a hurry.

George was my older brother, and Pa set a lot of store by him. It was generally accepted that he would inherit being the oldest and all, so I made plans of my own. I wanted to go east to Saint Louis and study for the law. Pa didn’t think much of it at first, but Ma slowly changed his mind, as she was prone to do. She made Pa think it was his idea, and if it was his idea, hell wouldn’t have it until it came to pass.

The dust was nearer now, so I stepped around the corner to the summer kitchen and checked the loads in Ma’s old Greener. I took it back to the front porch and laid it in her favorite flower box where no one could see it. Then I went into the parlor and strapped on my gun belt, checking the loads in my Colts .44. I went back on the porch and looked to the barn. The hay loft doors were now slightly cracked open and I could see the glint of a Henry barrel. Tom was ready.

The summer before I was to go to Saint Louis, we had rounded up five hundred head of fat cattle, and got them ready to drive to the railhead by Santa Fe. I had my gear packed and ready for the drive, but Pa had different plans, and he took me aside.

“I know you’re every bit a good a hand as your older brother, but I need someone to stay with your ma. You’re in charge while I’m gone.”

I was disappointed, but then, Pa had left me in charge, so I swelled up some with pride. He left behind two broken down old cowhands, and I bossed them around pretty good. We mended fence and cut three big stacks of hay against the coming winter. We cleaned out the barn and spread manure on Ma’s garden plot. By the time Pa got back, those two old cowboys were worn to a frazzle and glad to see him, at least until we all learned the news.

Pa was driving a wagon instead of riding astride, and in the back of the wagon was a box with my brother George’s body in it. It seems they were fording a river when George’s horse stepped into a hole and panicked. George was thrown and despite being a good swimmer, he disappeared under the roiling water.

It took two days to find his body where it had snagged on some underwater roots. Pa sent the herd on with his foreman and took George to a nearby town tied across a saddle. There he had him put in a decent coffin and brought him home for burial.

After that, Pa was never the same. Oh, he still went about the business of the ranch, but his heart wasn’t in it anymore. Ma lived her own hell of losing a child, and I gradually took over the operation of the ranch. A few years after, Ma and Pa died within a week of one another, and I was left alone with the ranch.

Now, twenty five years later with two sons and my own love dead and buried on the knoll, it had come to this. The Brenton brothers had hired lawyers to research the deeds and holdings of the various ranches. They had driven off the weaker owners with threats of lawsuits and the one who resisted had been found dead. The brothers had succeeded in amassing a huge holding and all they lacked for building a cattle empire was sufficient water for their stock, so they were now after the T-J Connected. But the worst part was that my own son had thrown in with them.

James had always bucked my authority, from the first time he climbed into a saddle. He was a top hand on the ranch, I’ll give him that, and he was never lazy, but if I said black, he said white. Of late, he had been running with that Brenton crowd, and the last time Tom had gone to Dentonville, his younger brother had braced him. Tom simply put his big hand on his younger brother’s shoulder and gave it a powerful squeeze. As James’ face turned white, Tom quietly reminded him that he could whip him three ways to Wednesday any day of the week, and asked if he wanted Tom to demonstrate right there on Main Street in front of everybody. James shook his head no, and that was the end of it.

The sun was now in the lower branches of the big cottonwood, and I could hear the steady drum of hooves. From the sound, I estimated about ten riders, and from the dust, they would just be crossing Woods Creek, which was dry this time of year. In the barnyard, three young hens were pecking at something under the watchful eye of an old rooster. The horses in the corral had their necks craned in the direction of the coming riders, their ears perked and alert. Far off to the south, three hands were supposed to be mending fence. I couldn’t tell if they were aware of the coming confrontation, but in any case, they were far too distant to help.

The drumming of the hooves paused. They had arrived at the east gate. I went back into the parlor and picked up my old Henry. I levered a round into the chamber as I stepped back on the porch and laid it beside the shotgun in the flower box. I was as ready as I could get.

I seated myself in the porch swing and waited. I glanced at the barn in time to see Tom wave at me from the doors of the hay loft. Then he closed the door to a crack and I looked down the road.

To the east, the ranch road dipped into small wash and then climbed a small rise before disappearing from sight on the other side. The dust boiled up on the far side of the rise and then the first riders’ heads appeared. I counted nine, and James was in front, alongside the Brenton brothers.

The chickens scattered in panic as they rode into the barnyard and wheeled their horses to face the house. I stayed seated and looked my son in the eye until he became uncomfortable and shifted his gaze. Then I stood and walked to stand by the flower box. John and Harvey Brenton watched me with small, unconcerned smiles on their faces. Finally, Harvey spoke up.

“Reckon you know why we’re here. Lawyer Davis says you got no legal claim to nothing other than the two hundred acres your buildings sit on. The rest is open range that you got no claim on.”

He paused, waiting for me to answer, and I did.

“We claim the entire T-J connected by right of more than fifty years possession, and we also hold proved up deeds to all the water holes, springs, dams and water rights.”

Harvey glanced at his brother. They had not known about the deeds Pa had filed on the water holes. Without the T-J water, their scheme was worthless. They decide to bluff. John Brenton nudged his horse forward a step or two.

“Them deeds ain’t worth nothing. We’re claiming the T-J.”

I looked at James.

“Are you going to side with these skunks against your own kin? They’re determined to have the T-J and I’m just as determined to deny them, so in a few moments, there will be blood spilled in this old barnyard. Where will you stand, James? I won’t shoot my own son, so I guess you’ll have to shoot me.”

His eyes widened in realization. This was not some lark where he could visit old resentments on me. This was serious business and people could die, including me. He hesitated, glancing sideways at the Brentons. Then he shrugged.

“Reckon I’ll put my horse in the corral. I can’t go against kinfolk.”

He wheeled his horse and started for the barn.

‘Hold up there, James,” Harvey Brenton barked. “You stay put until I give you my leave!”

James turned and faced the remaining eight riders. A look of anger crossed his face, but was quickly replaced by a look of resolve that I had seen many times. But this time, there was a maturity in it, rather than the sullen, resentful look I had come to know so well.

I looked over the Brenton riders. They were all saloon slugs and Dentonville low life, but they were all armed. I glanced up at the hay loft and was gratified to see an unwavering Henry barrel poking out of the cracked doors.

“You and your thieving brother can just turn around and ride on out of here, Harvey Brenton. As I said, I hold deeds to all the water on the TJ, so you just take your collection of bums and drunks and head back to Dentonville where you belong. The TJ is ours, and it will stay that way.”

If it hadn’t been for Red Saunders, a local bully-boy who sat his horse off to my left, it might have ended then and there. But I guess he must have taken real offense at my description of the Brenton crew because he jerked his Winchester out of its scabbard and tried to pull down on me. His horse spooked a little at the sudden movement, and before he could get set again, Tom’s Henry spoke from the hay loft, and Red’s worries were over.

The Brenton boys spun as one toward the barn and both Tom and James were firing. John Brenton jerked and fell from the saddle, and I felt Ma’s old shotgun slam my shoulder as a load of buckshot found Harvey Brenton. For a moment, he stared at me in astonishment and realization. Then he slumped to the ground. I swung the barrel to cover the others, and Tom kicked open the hay loft doors, jacking in another round. James nudged his horse and moved behind the remaining men, gun drawn and steady. We had them boxed.

Stunned at the sudden violence, the remaining five riders stared in silence, slowly moving both hands to their saddle horns and far way from their guns.

“Drop those gun belts and rifles and then back away!’

They complied, and James dismounted, gathering up their arms.

“I’ll leave your guns with that no account town marshal in Dentonville. You can pick them up there. Now pick up this trash from my barnyard and get off my land. And if I ever see any of you on the TJ again, I‘ll kill you without warning.”

Tom came down from the loft and stood beside his brother as we watched them ride away. He briefly put his arm around James’ shoulders, and then went to the pump for a drink.

“James.”

He looked up to me where I still stood on the porch.

“Come up here James.”

He mounted the steps and stood there looking at me, his eyes no longer defiant. I backhanded him hard across the mouth. He took a step back and stared at me, his upper lip beginning to bleed.

“Don’t you ever go against your family again. Not ever!”

For a moment he just stood there and then he began to smile with his still bleeding lips.

“Reckon I had that coming. I’ve been sassing you for years when I should have been respecting you. It won’t ever happen again.”

I nodded and smiled back at him.

“Good. A son should always respect his mother.”