- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- English Literature

William Shakespeare: An Introduction

His life

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-on-Avon, Warwickshire, on April 23, 1564, the son of a prosperous wool and leather merchant. Very little is known of his early life. From parish records we know that he married Ann Hathaway in 1582, when he was eighteen and she was twenty-six. They had three children, the eldest of whom died in childhood.

Between his marriage and the next thing we know about him there is a gap of ten years. Probably he became a member of a traveling company of actors. By 1592 he had settled in London, and had earned a reputation as an actor and playwright.

Theaters were then in their infancy. The first (called The Theatre) was built by actor James Burbage in 1576, in Shoreditch, then a suburb of London. Two more followed as the taste for theater grew: The Curtain in 1577 and The Rose in 1587. The demand for new plays naturally increased. Shakespeare probably earned a living adapting old plays and working in collaboration with others on new ones. Today we would call him a “free lance,” since he was not permanently attached to one theater.

In 1594, a new company of actors, The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, was formed, and Shakespeare was one of the shareholders. He remained a member throughout his working life. The company was regrouped in 1603, and renamed The King’s Men, with James I as their patron.

Shakespeare and his fellow actors prospered. In 1598 they built their own theater, The Globe, which broke away from the traditional rectangular shape of the inn and its yard (the early home of traveling bands of actors). Shakespeare described it in Henry V as “this wooden O,” because it was circular.

Many other theaters were built by investors eager to profit from the new enthusiasm for drama. The Hope, The Fortune, The Red Bull, and The Swan were all open-air “public” theaters. There were also many “private” (or indoor) , one of which (The Blackfriars) was purchased by Shakespeare and his friends because the child actors who performed there were dangerous competitors (Shakespeare denounces them in Hamlet).

After writing some thirty-seven plays (the exact number is something which scholars argue about), Shakespeare retired to his native Stratford, wealthy and respected. He died on his birthday in 1616.

His plays

Shakespeare’s plays were not all published in his lifetime. None of them comes to us exactly as he wrote it.

In Elizabethan times, plays were not regarded as either literature or good reading matter. They were written quickly (often by more than one writer), performed perhaps ten or twelve times, and then discarded. Fourteen of Shakespeare’s plays were first printed in Quarto (17cm x 21cm) volumes, not all with his name as the author. Some were authorized (the “good” Quartos) and probably were printed from prompt copies provided by the theater. Others were pirated (the “bad” Quartos) by booksellers who may have employed shorthand writers, or bought actors’ copies after the run of the play had ended.

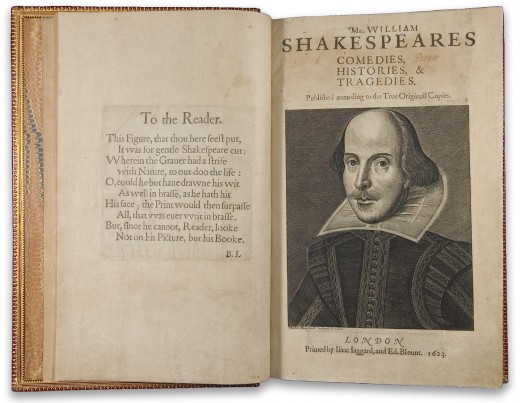

In 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, John Hemming and Henry Condell (fellow actors and shareholders in The King’s Men) published a collected edition of Shakespeare’s works - thirty-six plays in all - in a Folio (21cm x 34 cm) edition. From their introduction it would seem that they used Shakespeare’s original manuscripts (“we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers”) but the Folio volumes that still survive are not all exactly alike, nor are the plays printed as we know them today, with act and scene divisions and stage directions.

A modern edition of a Shakespeare play is the result of a great deal of scholarly research and editorial skill over several centuries. The aim is always to publish a text (based on the good and bad Quartos and the Folio editions) that most closely resembles what Shakespeare intended. Misprints have added to the problems, so some words and lines are pure guesswork. This explains why some versions of Shakespeare’s plays differ from others.

His theater

The first playhouse built as such in Elizabethan London, constructed in 1576, was The Theatre. Its cofounders were John Brayne, an investor, and James Burbage, a carpenter turned actor. Like the six or seven “public” (or outdoor) theaters which followed it over the next thirty years, it was situated outside the city, to avoid conflict with the authorities. They disapproved of players and playgoing, partly on moral and political grounds, and partly because of the danger of spreading the plague. (There were two major epidemics during Shakespeare’s lifetime, and on each occasion the theaters were closed for lengthy periods.)

The Theatre was a financial success, and Shakespeare’s company performed there until 1598, when a dispute over the lease of the land forced Burbage to take down the building. It was recreated in Southwark, as The Globe, with Shakespeare and several of his fellow actors as the principal shareholders.

By modern standards, The Globe was small. Externally, the octagonal building measured less than thirty meters across, but in spite of this it could accommodate an audience of between two and three thousand people. (The largest of the three theaters at the National Theatre complex in London today seats 1160.)

Performances were advertised by means of playbills posted around the city, and they took place during the hours of daylight when the weather was suitable. A flag flew to show that all was well, to save playgoers the wasted journey.

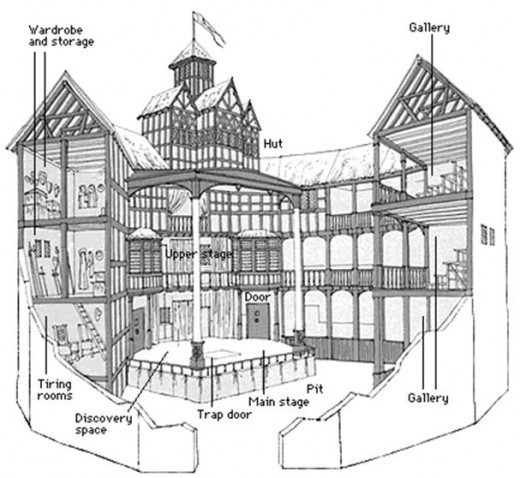

At the entrance, a doorkeeper collected one penny (about 60 cents today) for admission to the “pit” - a name taken from the old inn-yards, where bearbaiting and cockfighting were popular sports. This was the minimum charge for seeing the play. The “groundlings,” as they were called, simply stood around the three side of the stage, in the open air. Those who were better off could pay extra for a seat under cover. Stairs led from the pit to three tiers of galleries round the walls. The higher one went, the more one paid. The best seats cost one shilling, (or $7 today). In theaters owned by speculators like Francis Langley and Philip Henslowe, half the gallery takings went to the landlord.

A full house might consist of 800 groundlings and 1500 in the galleries, with a dozen more exclusive seats on the stage itself for the gentry. A new play might run for between six and sixteen performances; the average was about ten. As there were no breaks between scenes, and no intermissions, most plays could be performed in two hours. A trumpet sounded three times before the play began.

The acting company assembled in the Tiring house at the rear of the stage. This was where they “attired” (or dressed) themselves - not in costumes representing the period of the play, but in Elizabethan doublet and hose. All performances were therefore in modern dress, though no expense was spared to make the stage costumes lavish. The entire company was male. By law actresses were not allowed, and female roles were performed by boys.

Access to the stage from the Tiring House was through two doors, one on each side of the stage. Because there was no front curtain, every entrance had to be carried off. There was no scenery: the audience used its imagination, guided by the spoken word. Storms and night scenes might well be performed on sunny days in mid-afternoon; the Elizabethan playgoer relied entirely on the playwrights’ descriptive skills to establish the dramatic atmosphere.

Once on stage, the actors and their expensive clothes were protected from sudden showers by a canopy, the underside of which was painted blue, and spangled with stars to represent the heavens. A trapdoor in the stage made ghostly entrances and the gravedigging scene in Hamlet possible. Behind the main stage, in between two entrance doors, there was a curtained area, concealing a small inner stage, useful for bedroom scenes. Above this was a balcony, which served for castle walls (as in Henry V) or domestic balcony (as in the famous scene in Romeo and Juliet).

The acting style in Elizabethan times was probably more declamatory than we favor today, but the close proximity of the audience also made a degree of intimacy possible. In those days soliloquies and asides seemed quite natural. Act and scene divisions did not exist (those in printed versions of the play today have been added by editors), but Shakespeare often indicates a scene ending by a rhyming couplet.

A company such as The King’s Men at The Globe would consist of around twenty-five actors, half of whom might be shareholders, and the rest part-timers engaged for a particular play. Amongst the shareholders in The Globe were several specialists - William Kempe, for example, was a renowned comedian and Robert Armin was a singer and dancer. Playwrights wrote parts to suit the actors who were available, and devised ways of overcoming the absence of women. Shakespeare often has his heroines dress as young men, and physical contact between lovers was formal compared with the realism we expect today.

His verse

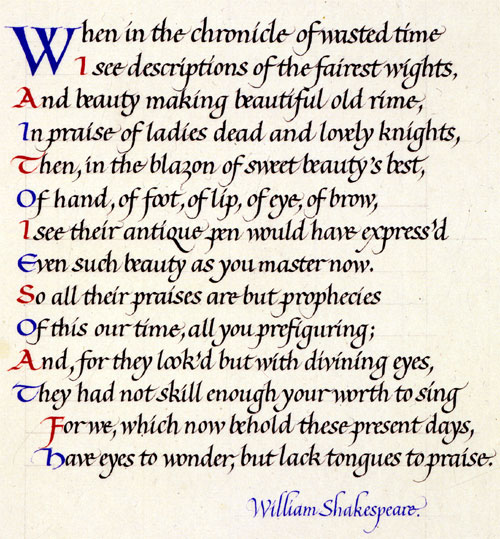

Shakespeare wrote his plays mostly in blank verse: that is, unrhymed lines consisting of ten syllables, alternately stressed and unstressed. The technical term for this form is the “iambic pentameter.” When Shakespeare first began to write for the stage, it was fashionable to maintain this regular beat from the first line of the play till the last.

Shakespeare conformed at first, and then experimented. Some of his early plays contain whole scenes in rhyming couplets - in Romeo and Juliet, for example, there is extensive use of rhyme, and as if to show his versatility, Shakespeare even inserts a sonnet into the dialogue. But as he matured, he sought greater freedom of expression than rhyme allowed. Rhyme is still used to indicate a scene ending, or to stress lines which he wishes the audience to remember. Generally, though, Shakespeare moved towards the rhythms of everyday speech. This gave him many dramatic advantages, which he fully and subtly exploits in terms of atmosphere, character, emotion, stress and pace.

It is Shakespeare’s poetic imagery, however, that most distinguishes his verse from that of lesser playwrights. It enables him to stretch the imagination, express complex thought patterns in memorable language, and convey a number of associated ideas in a compressed and economical form. A study of Shakespeare’s imagery - especially in his later plays - is often the key to a full understanding of his meaning and purposes.

At the other extreme is prose. Shakespeare normally reserves it for servants, clowns, commoners, and pedestrian matters such as lists, messages, and letters.