You're Saying it Wrong V: Folk Etymology Edition

Your Friendly Neighborhood Grammar Geek Volume IX

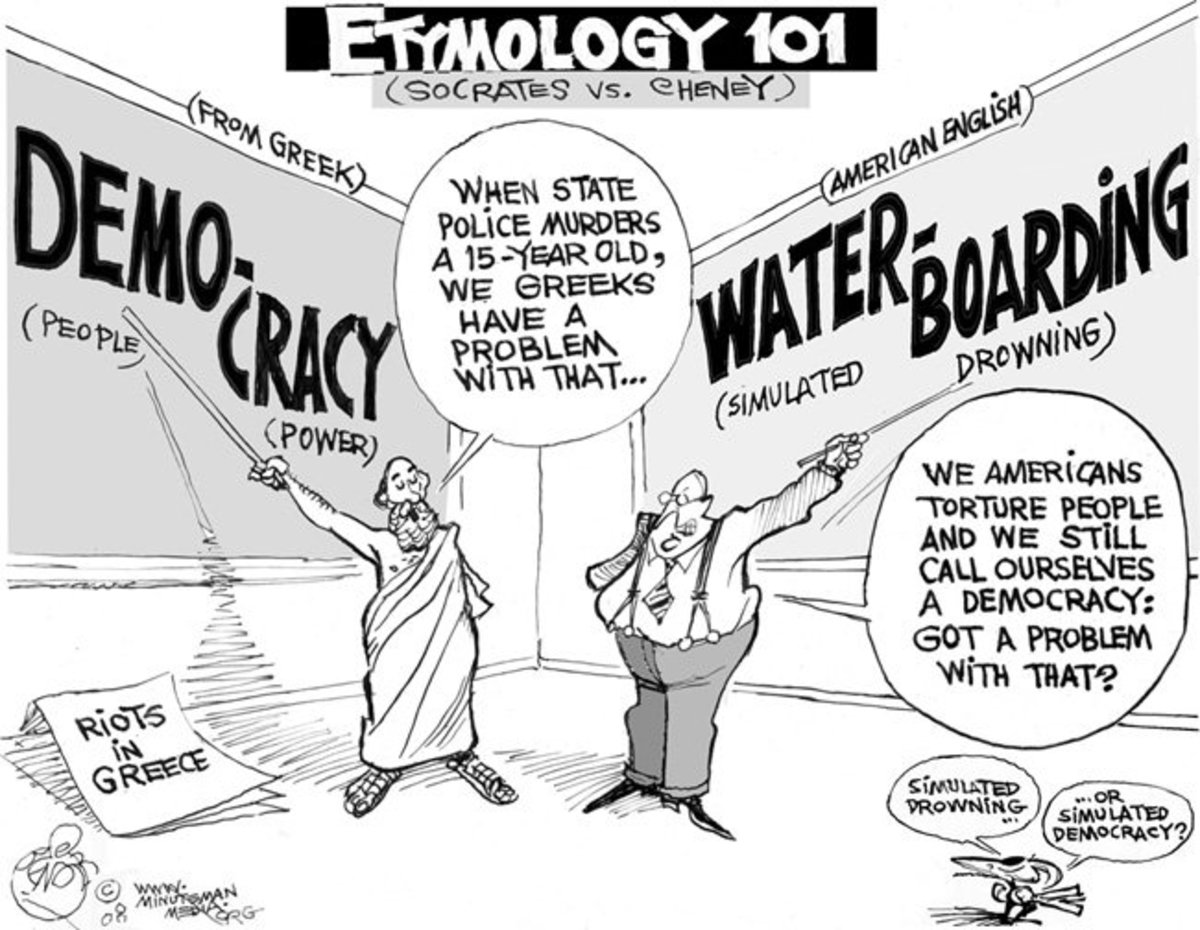

Lots of words and phrases in English are the result of a process called Folk Etymology. This is a linguistic shift in which an unusual or foreign word gets changed to a more familiar word. Sometimes the reasoning behind the change makes a certain kind of linguistic sense, even if the change is based on an incorrect assumption. Sometimes it doesn’t make much sense at all and is only based on someone’s mistake in pronunciation or something like that.

This edition of You’re Saying it Wrong will take a look at several folk etymologies, a couple of which have become standard. The ones that have become standard are no big deal; you don’t have to worry about them. I include them to illustrate that once a nonstandard usage has been in use for a long enough time it will become standard, that there's nothing anybody can do about it, and that there’s nothing wrong with it. Language evolves over time. The folk etymologies that have not yet become standard are, well, nonstandard. If you use them, it may reflect poorly on you, even if the person passing judgment often uses a different (but standard) folk etymology. It doesn’t seem fair, but there it is.

People Say, “...At His Beckon Call”

They Mean, “…At His Beck And Call”

Here’s why:

When modern people want someone to come over here, they don’t “beck.” They beckon. Or they call. Sometimes they both call and beckon. If someone is available to assist you at all times, however, they are said to be “at your beck and call.”

Beck is an archaic short form of beckon. It has fallen out of use in much the same way the positive adjective groovy has fallen out of general use, and parachute pants have fallen out of fashion. The point is, for whatever reason, people don’t say beck anymore. Now consider that the word and often gets reduced to a mere grunt in informal speech. Read the following lunch order out loud to see what I mean:

“Give me a ham and cheese sandwich, a side of mac and cheese, and a coffee, cream and two sugars.”

Is it any surprise that the phrase “at my beck and call” gets heard as “at my beckon call?” Add to that the fact that nobody says beck anymore, and the change even makes a certain amount of logical sense. But this usage hasn’t become standard, and here’s my theory about why: it misuses beckon, which is either a verb (“I’ll beckon when I want you to come.”) or a noun (“I mistook your beckon for a stretch.”) But it cannot function as an adjective, which is the only part of speech it can be when it finds itself between a possessive pronoun like your and call. Any word that goes there needs to be modifying call. The following examples work: “…his angry call…her shrill call…my loudest call….etc.” But what kind of call is a “beckon call?” Nobody knows.

Beckon call remains nonstandard. Do not use it.

(Thanks to hubber Tom Koecke)

People Say, “Very Close Veins”

They Mean, “Varicose Veins”

Here’s why:

Veins are blood vessels that bring blood back toward your heart (as opposed to arteries, which send blood away from your heart). This is a necessary oversimplification; I'm a linguist not a biologist. Veins have little one-way valves in them to stop gravity from making your blood flow backward. Interestingly, these valves don’t work when you’re upside down, which is why blood rushes to your head when you stand on it. The valves in your veins stop your blood from rushing to your feet when you stand right side up. When the valves work properly, a little blood goes through them every time your heart beats, and then they close, preventing any backflow. Next heartbeat, more blood flows up through the valve, pushing the earlier blood up through the next valve, and so on. But when one of those valves fails, blood starts leaking back through it, down into the part of the vein it just left. Obviously, there’s only so much room in each bit of vein, and if this goes on, the vein will start to swell, and even sag, under the pressure of all this extra blood. These swollen veins stand out, causing the skin to bulge. When failing valves cause your veins to swell, sag, bulge, and appear twisted or ropy, you are said to have varicose veins. The descriptor varicose comes from the Latin word varix, which itself means “a swollen vein.” The –ose suffix is an adjective marker, which we see in other Latin-derived words like bellicose (warlike) and lachrymose (sad).

So why do people keep saying they have “very close veins?” Well, varicose sounds a heck of a lot like very close, and how many of you knew what varicose meant before you read the above paragraph? Even if you knew that it’s varicose and not very close, you probably didn’t know why. (I didn’t until I looked it up, so don’t feel bad.) So you have this esoteric word, varicose, that practically nobody understands, being used to describe veins that happen to be very close to the surface of your skin. It’s easy to see how people who don’t know what varicose means (which is practically everybody) would start saying very close instead.

Very close veins remains nonstandard. Don’t use it.

People Say, “Can I Borrow Your Wheelbarrel?”

They Mean, “Can I Borrow Your Wheelbarrow?”

Here’s why:

A wheelbarrow is a small cart that people use to move stuff over short distances. Gardeners use them in the backyard; construction workers use them on a build site. These days, they typically have one wheel in front, two handles in back, and two skids underneath. These things are very common. Almost everybody reading this has probably at least seen one, if not used one several times. How did its name get corrupted?

Well, like varicose, it sounds a lot like something else. Wheelbarrow and wheelbarrel sound an awful lot alike, especially if you’re not listening closely (or speaking clearly). Now consider that wheelbarrow is a compound word (wheel + barrow) and that one of those words is kind of unusual. We’ve all seen wheels without barrows, but who has seen a barrow without a wheel? Now consider that barrow by itself doesn’t mean the thing that sits on top of the wheel in a wheelbarrow. It means the whole darn wheelbarrow. It can also mean a handbarrow, which, like a wheelbarrow, is a device for moving stuff around, but, unlike a wheelbarrow, has no wheel, but two sets of handles, requiring two people to use it. Barrow also means a burial mound. Frodo and his companions get trapped in a barrow in Fellowship of the Ring (the book, not the movie). And, even more obscurely, barrow can mean a male pig that was castrated before it grew up. Confusing.

Add to all of this the fact that if you take half a barrel, and put a wheel on one end, handles on the other, and skids underneath, you’ve got yourself a wheelbarrow. Probably a lot of folks have built homemade wheelbarrows just like this. Seems like it makes a lot of sense to call it a wheelbarrel, doesn’t it? Except it doesn’t.

Wheelbarrel remains nonstandard. Don’t use it.

People Say, “Sparrow Grass”

They Mean, “Asparagus”

Here’s why:

Asparagus isn’t grass at all. It’s a perennial plant that has a woody stem, and people can eat the new shoots in the springtime. They’re delicious. The word comes from Latin, twice. During medieval times, Latin was a lot more useful in everyday life than it is today, and students learned it so as to be able to talk to people from other countries in a common language. Languages that get spoken tend to get changed by their speakers. Classical Latin had the word asparagus, but by the time Old English had become Middle English (and the speakers of it needed a word for the asparagus plant), the word had shifted to something like sperage, and that’s what English speakers called the plant until the Age of Enlightenment rolled around.

Enlightenment scholars placed a very high value on anything from ancient Greece or ancient Rome. Some might argue that they over-valued Greco-roman stuff, but that’s beyond the scope of this article. Suffice to say that some Enlightenment botanists discovered the word asparagus in Classical Latin texts, and on the principle that if it’s Roman, it’s better, they started insisting that everyone call it asparagus instead of the “corrupt” sperage. Back in those days, folks paid a lot more attention to educated people than they do now, and even liked to seem educated themselves, so the “new” word for the plant caught on, in spite of the fact that we already had a perfectly good word for it.

Now let’s move forward a few years, and think about how beginnings and endings of words tend to get clipped off in informal speech. Imagine a farmer telling his kids, “Come ’n’ help me cut some ’sparagus for supper.” See? Now imagine that you and everyone you know has been calling it ’sparagus all your life and you’ve never seen the word in print. You know what a sparrow is, and you know what grass is, and ’sparagus kind of sounds like sparrow + grass, especially if you add a dash of hypercorrection to the mix.

Sparrow grass remains nonstandard. Don’t use it.

People Say, “Chaise Lounge”

They Mean, “Chaise Longue”

Here’s why:

As you have probably guessed, chaise lounge comes to us from French, but it didn’t survive the trip intact. Back in France, that long chair is called a chaise longue. (Note the inversion of the u and the n! It’s important!) A chaise in France is a chair in England. And of course, French longue translates to English long. Consider that in French, the adjective usually goes after the noun it modifies instead of before it as in English, and you will see that chaise longue simply means long chair.

But that’s too easy. Snooty folks who spend a lot of time lounging around on the lawn can’t go around calling things by their English words (or at least, so they thought once upon a time). So instead of long chair, the thing was called a chaise longue. But observant readers will already have seen the similarities between the words longue and lounge, especially since I pointed it out in the last paragraph. Those two words are really, really easy to mix up, even in print. Probably many readers did a double-take when they saw chaise longue and chaise lounge right next to each other. I went over this section several times, very slowly, to make sure I hadn’t mixed the words up, and I’m still not a hundred percent sure there isn’t a mix-up in here somewhere. Now consider what you do on those long chairs—you lounge on them, right? Exactly. This mistake has been made so often, so consistently, by so many people, that it’s not a mistake anymore.

Interestingly, the English word lounge itself may come from a related French word that means “to stretch out,” or “to become longer.”

Chaise lounge has become standard. Use it freely. Chaise longue is also standard, but use it at your own risk: it will probably make you sound overly posh.

People Say,: “How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck?”

They Mean, “Why Would a Groundhog Throw Wood in The First Place?”

Here’s why:

The critter in question, Marmota monax, neither eats wood nor throws it, so that name doesn’t make much sense. So why is it called a woodchuck? Well, the things don’t live in Europe. Bear with me.

When European people first came to the Americas, they ran into all kinds of animals that they’d never seen before, like skunks, possums, and woodchucks. They had no names for these strange creatures, so they did what anyone does when they want to know something—they asked somebody. The somebodies they asked were the only somebodies around—the local Native Americans. “What do you call that?”

When a European asked that question about Marmota monax, the answer was something that has been transcribed as otchec or wuchak or even ocqutchan, depending on where in the Americas the European happened to be, and which language the native neighbors spoke. The English have a long tradition of transliterating (some would call it ‘corrupting’) words from other languages to sound more English. For example, think about the London place names Elephant and Castle and Marylebone, and the English name of pretty much every town in Ireland. Otchec doesn’t very English at all, but it does kind of sound like woodchuck if you stretch your ears around it. Woodchuck has the added advantage of being easier for an English speaker to say, or at least more familiar-sounding. So the otchec ended up getting called woodchuck (also groundhog and, for some reason, whistle-pig. No, really!)

Woodchuck is standard, so use it freely. Its history is an interesting example of transliteration of borrowed words, though.