Amalia Riznich: a Beautiful Foreigner to Whom Alexander Pushkin Dedicated His Poems

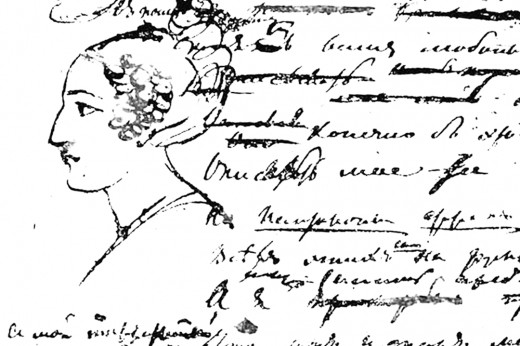

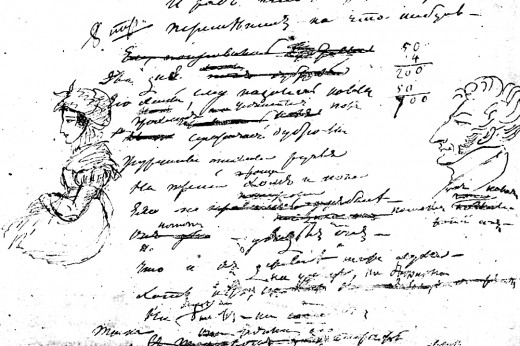

Some people may leave their mark on history, while others live their lives and disappear without a trace. Only their closest relatives remember them, and then merely for a few generations. Such was the fate of Amalia Riznich, also spelled as Riznić or Risnich (Serbian Cyrillic: Ризнић). The memory of her would probably have faded entirely if the famous Russian poet Alexander Pushkin had not fallen in love with her. Not even her actual portrait has survived; only numerous sketches made by Pushkin in his manuscripts remain.

Early Life and Origins

Amalia's origin is unclear. Professor Konstantin Zelenetsky (1812 or 1814–1858) published an article based on the recollections of Odesa's old-timers in 1856. According to it, she was half German and half Italian, with perhaps some Jewish ancestry. The article also states that her father was a Viennese banker named Ripp. However, previously, people who visited the Riznichs' house, including Pushkin, believed that Mrs. Riznich was from Genoa, Northwest Italy.

Serbian Professor Pantelija Srećković (1834–1903) also recalled that she was an Italian but from Florence, as cited in a 1892 article by Professor Mikhail Khalansky (1857–1910). Srećković studied in Kyiv in the 1850s. There, he met Amalia's husband, who spoke of his first wife and Pushkin. However, another Serbian professor, Alimpije Vasiljević (1831–1911), who also met Amalia's husband while studying in Kyiv in the 1850s, wrote in his memoirs that Mrs. Riznich was a Serb from Vojvodina.

Amalia's exact date of birth is unknown. According to documents from the Vienna archive, Amalia Rosalia Sofia Elisabetta Ripp (her full name at birth) was baptized on December 29, 1801, in St. Johann Nepomuk Parish Church in Vienna, the capital of Austria. Therefore, we can assume that she was born in Vienna shortly before.

From the same documents concerning Amalia's baptism, we know the names of her parents: Johann-Baptist Prokop Ripp and Franziska Wilhelmina, née von Dirschmidt. The prefix von in her mother's maiden name indicates her German descent. And Amalia's father's second name, Prokop, is of Slavic origin. That may support the version about her Serbian roots.

There is also some information about Amalia's father's occupation. The baptismal record states that he was a homeowner living in Vienna at Leopoldstadt, No. 455. There is also the 1834 document on the wedding of Amalia's brother Karl von Ripp (1802–1867). It listed their father's position as Director of Supply Office for Baron Wimmer's Army on the Rhine.

Husband and Marriage

Serbian origins may also have contributed to the Ripp family's acquaintance with Amalia's future husband, a Serb from a wealthy merchant family, Jovan (also Ivan or Giovanni) Riznich (1792–1861). He was born in the Imperial Free City of Trieste, located in northeast Italy, which at the time belonged to the Habsburg monarchy. His ancestors emigrated there in the 18th century from Sarajevo, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire (now part of Bosnia and Herzegovina).

Jovan Riznich graduated from the University of Vienna. Then, he lived there for some time and held a banking house. Later, he relocated to Odesa, then part of the Russian Empire (now part of Ukraine), and established a shipping office, primarily for the export of grain. According to his contemporaries, Riznich was a well-educated man, knew several languages, loved the theatre and Italian opera, and had an impressive home library.

As Odesa's old-timers recalled, in 1822, Jovan Riznich went to Vienna to get married and returned the following year with a young wife. However, according to records of documents issued to Riznich, necessary for the registration of the marriage, found in the archives of Trieste, he married as early as the end of 1820. All those documents are dated September 1820. For example, a certificate from September 17 confirmed the absence of obstacles to marriage. Their wedding was soon to take place in Vienna.

Then, Jovan probably went to Odesa to build his house and returned to get his wife after finishing the construction. The city authorities used to provide a plot of land for free with the obligation to build a house on it within two years. Also, before going to Vienna, Riznich, upon registration with the Odesa 1st Guild of Merchants, fulfilled the oath of allegiance to Russia on January 22 (January 10, Old Style), 1822.

Arrival in Odesa

The Riznichs, accompanied by Amalia's mother, arrived in Odesa in the spring of 1823. By that time, they had a son, Stefan (Stepan), who was about a year old, but he soon died. Amalia's mother spent several months in the city and left.

Jovan Riznich enjoyed a prominent position in Odesa, and his young wife immediately found herself at the center of attention. Especially since she loved parties, dancing, and playing cards. Those around her unanimously noted Amalia's incredible beauty, tall stature, and slenderness. However, some people said that she had too large feet, which she hid under a long, floor-length dress. We can also see some of her features in Pushkin's sketches, including large eyes, a humped nose, a slightly convex forehead, and a strong chin. Add to that a line from his humorous poem about Odesa ladies (unknown in full), "Madame Riznich with a Roman nose..."

Generally, Amalia stood out among the local ladies, which attracted a throng of admirers. One of them was the poet Vasily Tumansky (1800–1860). In a letter dated January 28 (January 16, Old Style), 1824, he wrote from Odesa to his cousin, "Our married women (excluding the beautiful and kind Mrs. Riznich) shy away from people, hiding either their simplicity or their ignorance under the guise of modesty." Another poet, Alexander Pushkin, fell under Amalia's spell shortly after he settled in the city.

Connection with Pushkin

Pushkin ended up on the Black Sea coast during his southern exile that had begun in the spring of 1820. The young poet, who served in the Collegium of Foreign Affairs, was transferred from Saint Petersburg (then the capital of Russia) to Chișinău, the administrative center of Bessarabia (now the capital of Moldova). The reason for the transfer to the outskirts of the empire was his anti-government and satirical poems, which mocked some influential individuals, including Emperor Alexander I (1777–1825).

Pushkin first visited Odesa in the autumn of 1820, on his way from Crimea to Bessarabia. In March 1821, he stayed there for several days, and in May 1823, for more than two weeks. It was a large and prosperous city with secular salons, balls, theaters, and other high-society entertainments that Pushkin missed in Chișinău. So, he obtained a transfer and settled in Odesa at the beginning of June 1823.

Soon, the poet met Amalia Riznich and fell in love with her. However, the true nature of their relationship is not entirely clear. Amalia's husband said that Pushkin hung around her, but she remained indifferent to him. Most researchers agree that Pushkin's love was unrequited, but the version of an affair also exists.

Departure Abroad

Anyway, their relationship did not last long. On January 13 (January 1, Old Style), 1824, Amalia gave birth to a son named Alexander. After that, her health deteriorated. She showed signs of consumption. In May 1824, her husband sent her to Switzerland for treatment. He accompanied his wife to the town of Brody (now a city in Ukraine) on the Russian-Austrian land border, but urgent business forced him to return to Odesa. In the fall, he planned to join her and go to Italy together to spend the winter.

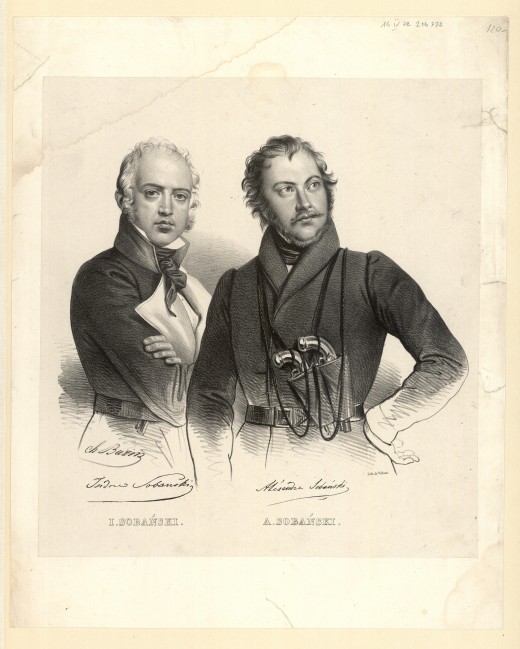

In Odesa, people said that the wealthy landowner Izydor Sobański caught up with Amalia abroad, saw her off to Vienna, and left. However, Polish Count Izydor Sobański (1791–1847) travelled through Italy, France, and England from 1816 to 1827 after his marriage. So, it is unlikely that he could follow Amalia. Probably it was his brother, Alexander Udalryk Sobański (1794 or 1797–1861), who lived in Odesa from 1820.

Their uncle, the wealthy merchant Hieronim Sobański (1781–1845), also lived there. His wife, the Polish adventuress Karolina Sobańska (circa 1794–1885), was another of Pushkin's muses. Her relative, the famous Polish princess Rozalia Lubomirska, died on the scaffold during the French Revolution (1789–1799).

However, Professor Srećković told a different story about Amalia's trip abroad. According to him, the servant who accompanied Amalia reported to her husband that the Polish prince Jabłonowski had followed her to Florence and had won her favor there. It is difficult to say which Jabłonowski he had in mind. There were several of them, for example, two brothers, princes Antoni (1793–1855) and Stanisław (1799–1878) Jabłonowski. However, a superficial acquaintance with their biographies is not enough to say whether it could have been any of them.

Anyway, Zelenetsky collected the memoirs of Odesa old-timers more than 30 years after the events described. And Srećković told Khalansky what he learned from Amalia's husband almost 40 years after Zelenetsky's publication. So the accuracy of that information is questionable. We cannot even say for sure whether any of Amalia's admirers followed her, or whether these were just rumors circulating at the time.

All we know for sure is that Amalia never returned to Russia. In Odesa, people said that she died in poverty, in the care of her husband's mother. However, according to Professor Srećković, Jovan Riznich never refused her financial support. The death certificate states that Amalia Riznich died at the age of 23 from chronic chest disease on June 23, 1825, at three o'clock in the morning in the Riznichs' house in Trieste. Also, according to the certificate, she was childless, which means her son was probably dead by then.

Further Events

Mr. Riznich in Odesa learned of his wife's death around July 8 (June 26, Old Style), as follows from the postscript to his letter to his friend. In the same month, Vasily Tumansky wrote the sonnet On the demise of R (Russian: На кончину Р). In the text, he mentioned fickle admirers, already attracted by other beauties, possibly hinting at Pushkin, to whom he dedicated his sonnet.

After Amalia left Odesa, Alexander Pushkin courted Elizaveta Vorontsova (1792–1880), the wife of the Governor-General of New Russia & Bessarabia. Soon, however, the police in Moscow opened Pushkin's letter to his friend, in which he wrote favorably of atheism. That was the reason for the poet's resignation from service and exile to his parental estate, Mikhailovskoye, in northwest Russia, under the supervision of local authorities. The poet left Odesa at the end of July or the beginning of August 1824.

According to the decrypt of Pushkin's notes, he learned of the death of Amalia Riznich on August 6 (July 25, Old Style), 1826, in Mikhailovskoye. Later, Tumansky wrote to him in a letter dated March 14 (March 2, Old Style), 1827, about the marriage of Jovan Riznich with Countess Paulina Rzewuska (1808–1866), the sister of Karolina Sobańska.

Riznich subsequently went bankrupt in the early 1830s. Then he entered the civil service and moved to Kyiv with his family. At the same time, he began to apply for inclusion in the Russian nobility. The Kyiv Noble Deputies' Assembly decided to include the Riznich family in the genealogical book in 1847.

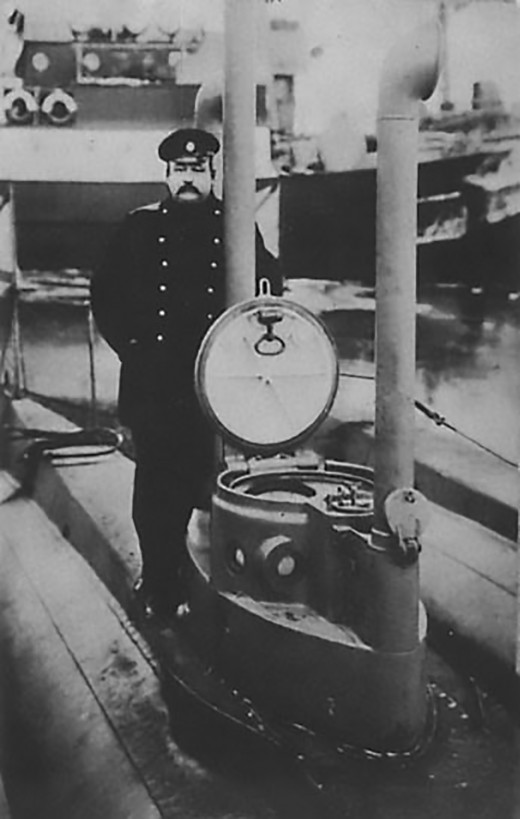

From his second marriage, Riznich had two daughters and three sons. Some of his descendants became quite famous. For example, his daughter, Maria (1827–1895 or 1914 or 1924), became renowned as the wife of the famous French occultist Joseph Alexandre Saint-Yves (1842–1909). Also worth mentioning is Ivan Riznich (1878–circa 1920), the grandson of Jovan Riznich. He was one of the first Russian submarine officers and the author of most of the Russian standard submarine commands still in use today.

Amalia Riznich in Pushkin's Works

There is no consensus on Amalia's influence on Pushkin's life and work. Researchers associate at least two elegies and some stanzas from the novel in verse Eugene Onegin (Russian: Евгений Онегин) with her. The 1823 elegy Will You Forgive Me My Jealous Dreams (Russian: Простишь ли мне ревнивые мечты), written in Odesa, reveals a picture of burning passion, along with the torments of jealousy. There is the same image of passion, but already gone, in the elegy Under The Blue Skies (Russian: Под небом голубым), written in 1826, when the poet learned of the death of Amalia Riznich. It expresses the indifference with which Pushkin accepted the news. In Eugene Onegin, written from 1823 to 1830, the same image of a woman appears, who made the poet experience all the torments of jealousy.

However, some researchers associate more of Pushkin's poems with Amalia Riznich, merging them into a single cycle. It reveals the story of love, which, having endured the torments of jealousy, faded away but returned several years later. It was no longer love for a real woman, but for her idealized image, the shadow of the deceased beloved.

There are also studies of literary inspiration sources for Pushkin's works. In particular, his aforementioned elegy of 1823 bears much in common with The Anxiety (French: L'Inquiétude) by the French poet Charles Hubert Millevoye (1782–1816). We can assume that Pushkin came across Millevoye's elegy, which was in tune with his recent torments of jealousy. Perhaps, exploration into poetry writing occupied him at that moment no less than the experiences of unrequited love for Amalia Riznich, which his new infatuation with Elizaveta Vorontsova had already supplanted. So, he may have wanted to compete with his fellow poets in the then-fashionable genre of poetry.

Pushkin's Letters to Amalia Riznich

In the 1970s, scholars of Pushkin from the USSR Academy of Sciences learned about his letters to Amalia Riznich, which could have been in a Serbian Orthodox church in Trieste (Saint Spyridon Church). They asked Soviet journalist Nikolai Prozhogin (1928–2012), who was then working in Italy, to try to find out something about that. There were no such letters in the church archives. However, the journalist discovered that the letters, if they ever existed, had burned during World War II, along with the house of Riznich's relatives in Herceg Novi, Yugoslavia (now Montenegro).

Yet the search was not in vain. Nikolai Prozhogin discovered some of the documents cited above, which clarified a few details of Amalia Riznich's biography and that of her husband. He also visited her burial place. From August 1, 1825, burials began outside the city at the Catholic cemetery of Sant'Anna. Amalia Riznich was one of the last to be buried in the old cemetery on the hill of San Giusto, near the Trieste Cathedral.

Today, the cemetery no longer exists. In its place is the Civic Museum of Antiquities J.J. Winkelman and the adjoining Orto Lapidario, which houses epigraphs, monuments, and sculptures from the Roman era. So, even the grave of Amalia Riznich has not survived. However, she continues to live in Pushkin's poems. The poet immortalized himself in his work and passed on a piece of his immortality to those he eulogized.

Sources and Further Reading

- Zelenetsky K.P. (1856). G-zha Riznich i Pushkin (Posvyashchaetsya P. V. Annenkovu). [Mrs. Riznich and Pushkin (Dedicated to Annenkov P.V.)]. Otzyvy o Pushkine s yuga Rossii. V vospominanie pyatidesyatiletiya so dnya smerti poehta 29-go yanvarya 1887. Collected by Yakovlev V.A. Odessa. 1887 (In Russian) https://www.litres.ru/book/vladimir-yakovlev/otzyvy-o-pushkine-s-uga-rossii-580765/

- Khalansky M.G. (1900). Pushkin i g-zha Riznich. [Pushkin and Mrs. Riznich]. Har'kovskіj Universitetskіj Sbornik. V pamyat' A. S. Pushkina (1799–1899). Kharkov (In Russian) https://z-library.sk/book/18438952/2899bc/%D0%A5%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9-%D0%A3%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%81%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9-%D0%A1%D0%B1%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA-%D0%B2-%D0%BF%D0%B0%D0%BC%D1%8F%D1%82%D1%8C-%D0%90-%D0%A1-%D0%9F%D1%83%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B0-17991899-%D0%B3.html?dsource=recommend

- Sivers A.A. (1927). Sem'ya Riznich. Novye materialy. [The Riznich Family. New Materials]. Pushkin i ego sovremenniki, issues XXXI-XXXII. Leningrad (In Russian) https://feb-web.ru/feb/pushkin/serial/psz/psz2085-.htm

- Prozhogin N.P. (2000). "Dlya beregov otchizny dal'noj…" V poiskakh Amalii Riznich. ["For the Shores of the Distant Fatherland..." In Search of Amalia Riznich]. Druzhba Narodov, No. 6. 2000 (In Russian) https://magazines.gorky.media/druzhba/2000/6/dlya-beregov-otchizny-dalnoj.html

- Shchegolev P.E. (1904). Amaliya Riznich v poehzii A. S. Pushkina. [Amalia Riznich in the Poetry of A.S. Pushkin]. Perventsy russkoy svobody. Moscow: Sovremennik. 1987 (In Russian) http://az.lib.ru/s/shegolew_p_e/text_0220.shtml

- Efros A.M. (1933). Risunki poeta. [Drawings of the Poet]. Moscow: Academia (In Russian) https://archive.org/details/1933_20230714/mode/2up