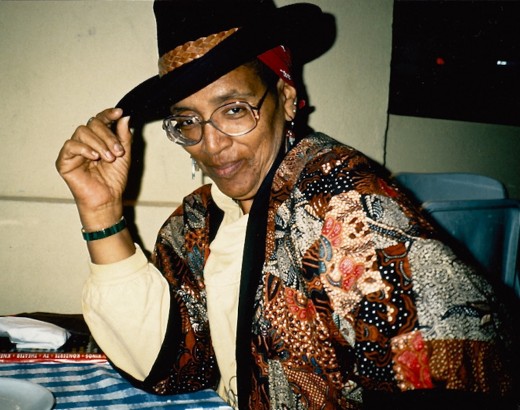

Audre Lorde’s “A Litany for Survival”

Introduction and Excerpt from “A Litany for Survival”

While a horde of literary analysts—here, here, and here—insist on positing Audre Lorde’s “A Litany for Survival” as specifically focusing on black women’s experience, especially the lesbian experience, the actual themes of fear, timidity, and resistance evoke responses universally.

The experiences of fear of negative reactions from one’s fellows affects anyone facing the challenges of living, which automatically comes with existential dread.

In Audre Lorde’s “A Litany for Survival,” the speaker’s rallying call to “speak / remembering / we were never meant to survive” countermands specificity such the widely touted “marginalized groups.”

The speaker is encouraging anyone who faces any challenge to use his/her voice against the forces that would suppress that voice.

The poem is displayed in free verse; its claim to be a litany is bit of a stretch but still it does somewhat parallel a ritualistic chant. Its lack of rhythm and rime invokes a untutored but pressing tone which represents the vulnerability of the lives it is attempting to dramatize.

The poem’s absence of traditional aesthetic conventions, that is poetic devices, including meter and rime, works to elevate the theme of survival over that of the usual poetic pleasantries.

(Please note: Dr. Samuel Johnson introduced the form "rhyme" into English in the 18th century, mistakenly thinking that the term was a Greek derivative of "rythmos." Thus "rhyme" is an etymological error. For my explanation for using only the original form "rime," please see "Rime vs Rhyme: Dr. Samuel Johnson’s Error.")

Excerpt from “A Litany for Survival”

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

who love in doorways coming and going

in the hours between dawns

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futures

like bread in our children’s mouths

so their dreams will not reflect

the death of ours;

To read the rest, please visit “A Litany for Survival” at Poetry Foundation.

Commentary on “A Litany for Survival”

A bevy of loud voices announcing and decrying oppression has driven a cottage industry for hauling in millions of dollars to spread their fictitious, vile lies. It is sad that a fine poet such Audre Lorde is most noted for her vacuous cries of oppression.

However, this poem offers a marvelous opportunity to glean truth about the human condition: the human heart and mind from birth are plagued, facing the challenges of fear, making hard choice, and just keeping body and soul together.

The complaints garnered for class, race, and gender warfare do not assist in that human struggle but instead obstruct the winning of the war against the real enemies of human welfare: ignorance, prevarication, and egocentrism.

First Movement: The Precarious Locus

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

who love in doorways coming and going

in the hours between dawns

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futures

like bread in our children’s mouths

so their dreams will not reflect

the death of ours;

The speaker begins by placing certain individuals at a precarious location “the shoreline” where two very different entities meet: water and land. This metaphorical locus implies that those who stand in such a place must balance their movements lest they stumble and fall.

That insecure stance then changes and focuses on decision making. Now certain individuals who already stand so tentatively must also make choices that affect their future. These people are the ones who “cannot indulge / the passing dreams of choice.”

And exactly who are such folks? Is anyone incapable of dreaming and choosing? Is anyone forbidden such dreaming and choosing? Only in the fantasy land of political correctness, identity politics, and victimhood ideology.

Instead of choosing to understand, work, struggle, and persevere within a system of democratic principles, it is easier to complain, denigrate, and blame others for one’s failures.

Many famous voices expressed the idea that the bulk of negative criticism against former president Barack Obama was because of his race, not because of his ruinous politics.

For example, former president Jimmy Carter opined, “I think an overwhelming portion of the intensely demonstrated animosity toward President Barack Obama is based on the fact that he is a black man.”

Another famous voice Oprah Winfrey chimed in about the Obama presidency: “I think there’s a level of disrespect for the office that occurs, and that occurs in some cases and maybe even many cases because he’s African-American.”

Additional commentaries playing the race card were Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose 2017 excruciatingly long article in The Atlantic not only plays the race card but also puts on display the whole deck.

And then there is David Axelrod, who screeched, “It’s indisputable that there was a ferocity to the opposition and a lack of respect to him that was a function of race.”

If so, how did Barack Hussein Obama get elected twice? He was still black before, during, and after his presidential campaigns.

The speaker of Audre Lorde’s “A Litany for Survival” is trying to articulate a position that simply does not exist in modern America. The Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 abolished systemic racism and sexism, just as the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13, 14, and 15 Amendments to the US Constitution abolished slavery.

Although latent vestiges of racism and sexism continue to exist in the population at large, it does not exist systemically as social justice activists, race baiters, and radical feminists have continued to proclaim.

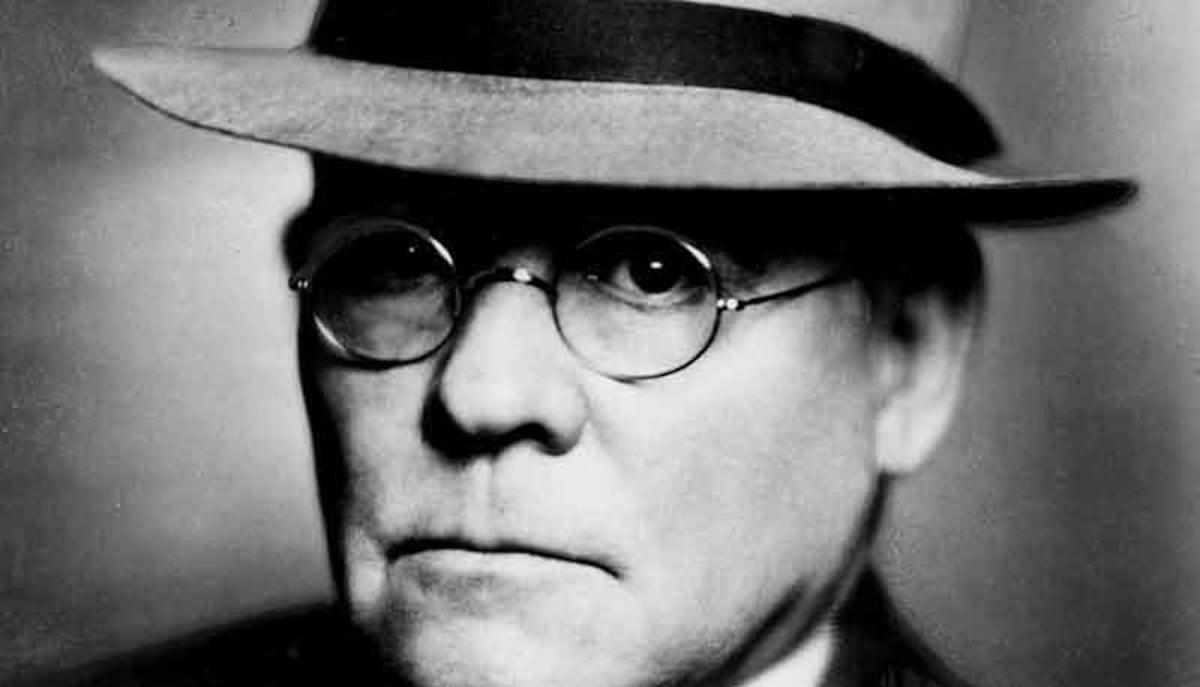

As noted economist Thomas Sowell has explained,

Racism is not dead. But it is on life-support, kept alive mainly by the people who use it for an excuse or to keep minority communities fearful or resentful enough to turn out as a voting bloc on Election Day

The loud voices announcing oppression have driven a cottage industry for hauling in millions of dollars to spread their fictitious, vile lies. Racial exhibitionists such as the aforementioned Coates as well as Ibram X. Kendi would have no career, no means of sustenance without the opportunity to push the false narrative of systemic racism.

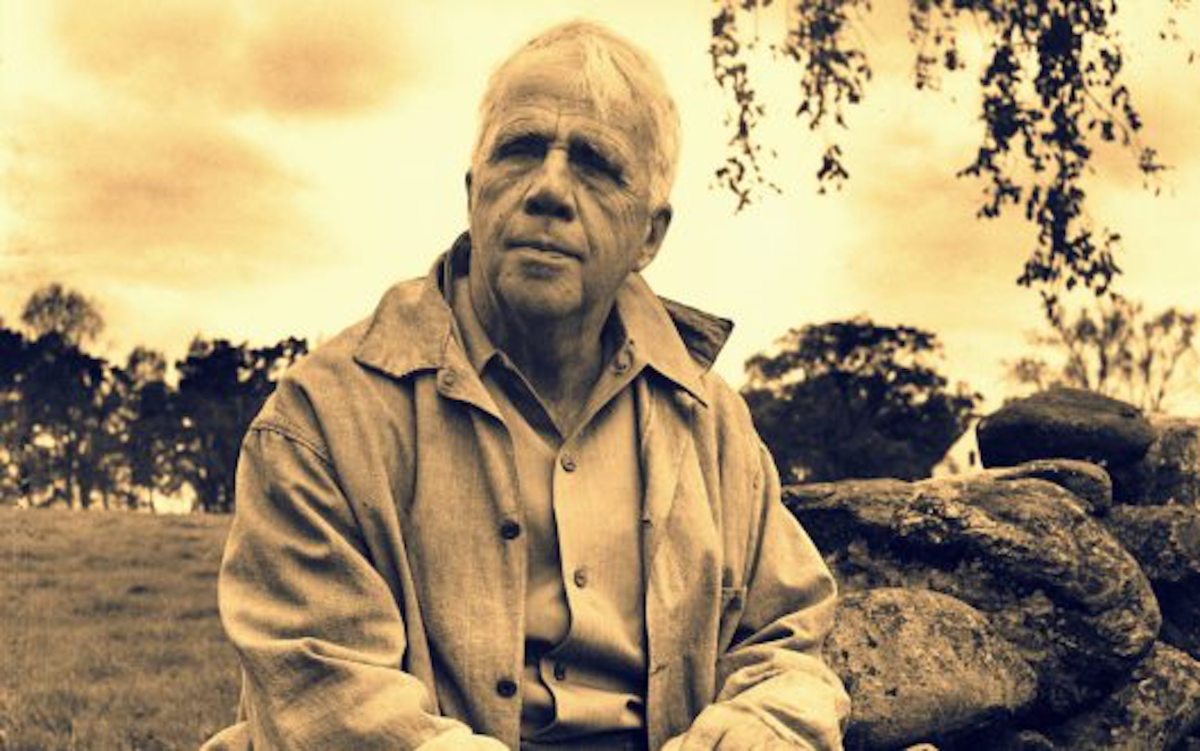

On the one hand, it is sad that a fine poet such Audre Lorde is most noted for her vacuous cries of oppression. On the other hand, Lorde’s poetry remains worth studying because she was able to craft worthwhile pieces, which make skillful use of poetic devices. And many of her best works offer insight into the human condition.

Those who buy into the critical race/sex theory of society continue to wallow in the slime of victimhood, as they miss the beauty and truth that could be appreciated if they turned their attention to other matters.

The issues that are most important to living the life of a human being can be addressed by concentrating on the profound existential questions of “who am I?” what is the purpose of life?” “does the soul exist?” “what happens after I die?” “how does one determine what is true and what is false?” “does God exist?” “who is God?”

Lorde’s speaker addresses the matter of having the ability to secure food for the children of these folks standing on the shoreline, fumbling for a way to stand. She implies a hope that such folks can give their children what they need so those children will not have to become aware that their parents lives revolved around dead dreams.

The contradiction here is palpable; the speaker seems to think that if the mother is able to give her child enough bread, the child will likely feel that he can dream his own dream and not have be bothered with worrying that his mother’s dreams were dead.

And if the mother cannot provide that bread? The child will, in fact, reflect the dead dreams of the mother? How? Seems that without food the child will die, and if the mother cannot provide for the child, she will not be able to have her own food.

The nonsense in these claims simply demonstrates the ludicrous nature of trying to express in poetry what cannot even be truthfully expressed in prose. As poetry and politics make strange bedfellows, playing the victimhood card and portraying truth make even stranger associates.

Second Movement: The Issue of Fear

The speaker then turns to issue of fear. Colorfully striping a line down the center of foreheads is merely a physical notation of that fear. But again the fear is limited to “those of us”—which is a big lie! Again, colorfully the speaker originate our fear with “mother’s milk”—which is true—we do all learn fear quite early in life.

However, that fear is innate and instilled for protection that we learn to keep away from dangers. It is not a “weapon” employed by “the heavy-footed” who are hoping to “silence us.” “Heavy-footed” most likely remains a synecdochical reference for men—the average man weighs more that the average woman.

The speaker then announces what she likely thinks is a grand and profound discovery: “We were never meant to survive.” Literally, the statement alone is quite true. Our mortal, physical encasements were obviously never meant to survive. But she is not expecting her readers to take that claim for what it actually says.

She expects her readers the hear that those heavy-footed ogres with fear as a weapon have planned for our demise: they don’t want us to survive; the amorphous they never meant for us to survive.

Third Movement: Afraid to Be Afraid

This movement simply runs through a catalogue of pairs of objects of fear that demonstrate all of the ways we are afraid: we’re afraid when the sun comes up and we’re afraid it won’t come up again; we’re afraid on a full stomach and just as afraid on an empty stomach.

We’re afraid when were are loved that we won’t continue to loved; we’re afraid when we speak that no one will hear us; but then if we don’t speak we’re still afraid.

Fourth Movement: Speech and Survival

As simplistic as the third movement proved to be, the fourth and final movement is even more plain and simple. The speaker has determined that despite all the fear that motivates us it still has to be “better to speak.”

And why is that? She does not say why it better to speaker; she only asks her audience to remember while speaking that “we were never meant to survive.”

So, what do we gain by speaking under such circumstances? If the “heavy-footed” are after us with their weapons of fear, they surely will not be thwarted by our speaking. Instead, they will likely be spurred on to cause us more fear and damage after we have spoken, especially if our speaking does any kind of damage to them.

And if we do not speak? Then nothing can happen. And if we believe that we were not meant to survive anyway, where are we then?

Of course, these questions sound ludicrous because they are responding to a discourse that was built out of fairy dust.

Ignoring the Social Activism

In my commentary on Audre Lorde’s “A Litany for Survival,” I have specifically concentrated on refuting the issues that are so widely claimed for this poem.

On the one hand, if one takes seriously the claims of oppression experienced by black lesbians and radical feminists, one may fall into the trap created by most postmodernists, who focus on identity politics and victimhood.

On the other hand, if one ignores the social justice angle that is stitched into this poetic piece and simply realizes the universality of the ideas of fear, the difficulty of decision-making, and the concerns of having enough sustenance for our offspring, then the poem can take on a whole new patina.

For the sake of the fine poet Audre Lorde, I suggest that a realization that all of humanity is faced with these issues—not just black lesbians and radical feminists—is vitally needed. The imagery, the structure, and movement of the poem make it worth studying.

Just filter out the victimhood ideology and remain skeptical of the poet’s ability to serve as soldier in the social justice war. Appreciating Audre Lorde’s poetic skills is much more important than agreeing with the wrong-headed ideology which continues to plague her reputation.

Other Audre Lorde Poem Commentary

- Audre Lorde’s “Father Son and Holy Ghost” Audre Lorde’s elegy "Father Son and Holy Ghost" revisits memories of a respected father, who has died and who served as a model for consistent behavior. The speaker’s quiet affection becomes evident as she relives special features of her father and her reactions to them.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Linda Sue Grimes