American Literature: Contemporary views on Charlotte Temple

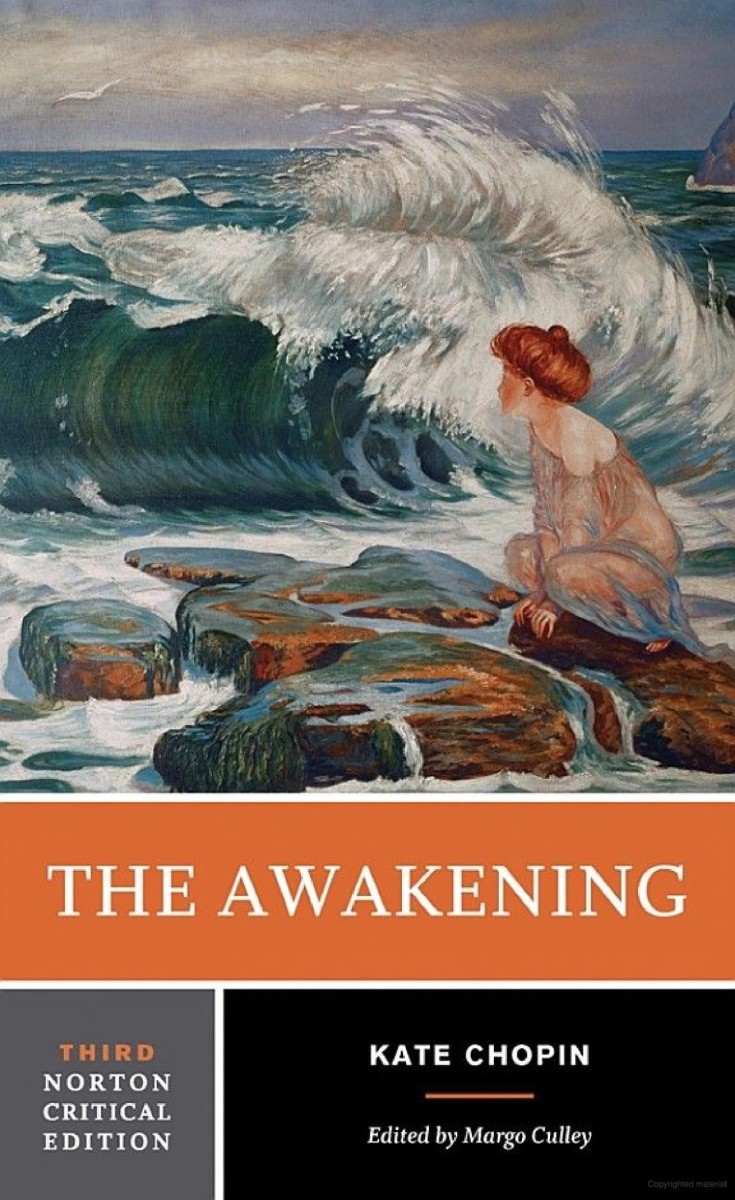

Perhaps the first American best-selling novel, Charlotte Temple has been called "the biggest bestseller in American History until Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom's Cabin in 1852" by Anne Douglas, editor for the Penguin Book edition of the novel. Despite its immense popularity when it first came out, by the time 1960 came around, acclaimed critic Leslie Fielder called Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte Temple (1791) a, “subliterate myth”. Fielder goes on to say that the novel is “hardly written at all”. While Fielder may be correct in assessing Charlotte Temple as such, questions as to the utility and relevance of such an assessment prove more interesting. Fielder’s assessment does not enlighten the twentieth century reader as to the value, purpose, or significance of Susanna Rowson’s “Tale of Truth” (880). Because Fielder’s assessment fails to achieve such ends, it holds no critical value despite any question of its accuracy.

Now, the point of this article isn’t to disqualify Leslie Fielder as valid critic. To do this would be to commit the same error in judgment to be discussed in detail here. Rather, it is informative to review 20th century criticism to look for errors in judgment that are instructive to us still today. Fielder, for example, wrote in 1960 when criticism was beginning to come around to see things from a Feminist perspective. Understanding Fielder’s place in history, it becomes easy to see why a novel that attempts to reinforce the social norms of women staying ignorant, in the home, and dependent upon men might be seen in such bad light. Furthermore, given Fielder’s time, there is nothing wrong with this interpretation. However, given that this article is being written fifty years after Fielder’s, the critical field has changed. Now, our task is to examine criticism as much as the texts. Therefore, with this in mind, let us approach Charlotte Temple in an attempt to understand how we should appreciate it now, since we no longer live in a culture like the one of 1791, or 1960 either, for that matter.

In the very beginning of the novel Rowson tells the reader she wants to, “be of service to…young and unprotected women in her first entrance into life” (881). Rowson sees dangers for these young women not only from “the other sex, but from the more dangerous arts of the profligate of their own” (881). Unlike twentieth century literature which has embraced a certain ambiguous attitude towards definite moral agenda’s within the work, Rowson makes her very specific moral agenda transparent. The agenda she sets forth is to teach a lesson to young women about the dangers of the world. Fielder refers to this teaching of a lesson with the concept of “subliterate myth”. Fielder seems to be saying that Charlotte Temple lacks significance because of its probable relationship with such myths. Inherent in this view is a twentieth century mentality that rejects the transparency of Rowson’s claims in the quotes above. This mentality, though it can serve to understand the evolution of literature since Rowson’s time, should not be used as criteria with which to reject works from that era as having merit.

Get your own copy of America's first bestseller

The only true way to criticize the work upon its own merit would be to examine Rowson’s agenda set forth in the preface with the realization of that agenda in the body of the novel. This is a two part question. First, whether or not Rowson’s contemporaries found the narrative to have enough credibility to lend the story proper authority. Second, whether or not twentieth century critics find the narrative to have enough credibility to lend the story proper authority.

The popularity of the novel at its time clearly illustrates Rowson had credibility in the eyes of her peers. The fact that people refused to believe it was fiction further illustrates the immense credibility the work must have had for its contemporary audience. This brings up a very significant point: Charlotte Temple was popular fiction. Sensationalized, short, episodic, and melodramatic all describe Charlotte Temple. This list of terms fits more closely with popular fiction reviews than serious literary criticism. A much more powerful criticism of the novel, one that Fielder may have been getting at by calling it a sub-literate myth, would be one that says: the contrived characters, melodramatic encounters, easily readable episodic format, and immense popularity amongst the general public suggests an accurate interpretation of Charlotte Temple should require nothing more of the text than criticism of popular fiction in our modern age.

Given the above, the second question, whether or not twentieth century critics found the narrative to have enough credibility, must be qualified by a further condition. This condition is an understanding of the critic’s perspective on Charlotte Temple. There is much evidence to suggest that, despite its lesson-oriented nature, the novel is little more than popular, or even, for its own time, pulp fiction. After all, it deals with the ruining of a young girl by world forces. It would be naïve of us to suggest that the sheltered young women who read this novel did not experience a moment or two of voyeuristic pleasure.

The novel even works to preserve the innocence of Charlotte long past when it is believable. Consider one of the climatic scenes of the novel, when Charlotte turns up at Mrs. Crayton’s house. Despite the extremity of the weather conditions, the obvious need of Charlotte, her desperate pleas, and the benevolent disposition of both men in the room, Mrs. Crayton inhumanly replies to her request, “the young woman is certainly out of her senses: do pray take her away, she terrifies me to death” (939). This incident, moreover, is not unique. In almost every chapter La Rue/Mrs. Crayton appears in her behavior as inexplicably malicious towards the person of Charlotte. Several chapters, particularly VII and XI, give further examples of how Rowson uses La Rue to force Charlotte into situations in order to maintain Charlotte’s innocence.

Never carry around a stack of books all over campus again! Get a Kindle!

Of course, on the surface, this was done to maintain a connection between Charlotte and the “young and unprotected women” Rowson intended the novel to morally instruct (881). One cannot, however, help but think there was something about Charlotte’s fate that thrilled young women who would never have the opportunity to be so taken advantage of. However you interpret it, this identification is central to the emotional force of the novel. This transparency, or “hardly written at all” aspect of the novel strengthens the argument to interpret it as popular fiction as does the reasons here discussed for its wide success at the time of its publishing.

From what little we have of Fielder’s criticism of the novel, it seems safe to assume that if Fielder felt the novel was simply popular fiction, he would have hardly taken the time to criticize it for being a “subliterate myth” given the subliterate nature of most popular fiction today. Therefore, if Fielder assesses the novel not as popular fiction, but literature, it would seem a frustrating task, one that might lead to the conclusion the novel was “hardly written at all”. This however, if it is true by Fielder’s standard, has failed to assert to us, given the genre of the work in question as that of popular fiction, anything regarding the significance, value, or purpose of Charlotte Temple. In modern terms, it’s like criticizing Stephen King because he’s not William Faulkner. My point is, such observations are irrelevant to anyone wanting to understand Stephen King, and therefore, would also be irrelevant to anyone wanting to understand Charlotte Temple. Perhaps such an assessment was what Rowson had in mind when referring to her novel as “the most elegant finished piece of literature whose tendency might deprave the heart or mislead the understanding” (881).

Citations

All numbered citations refer to the Norton Anthology of Literature, 6th Edition, Vol. A.

Books by Susanna Rowson

Other Hubs on American Literature

- Kurt Vonnegut's Version of the Fairytale Bluebeard: Writing About Writing For People Who Don't Read

Kurt Vonnegut, one of the most prolific if not best American writers of the second half of the twentieth century, first earned a reputation for himself as a science-fictionist with his early works, The Sirens... - Literary Criticism: The Tragedy of Joe Christmas from William Faulkner's Light in August

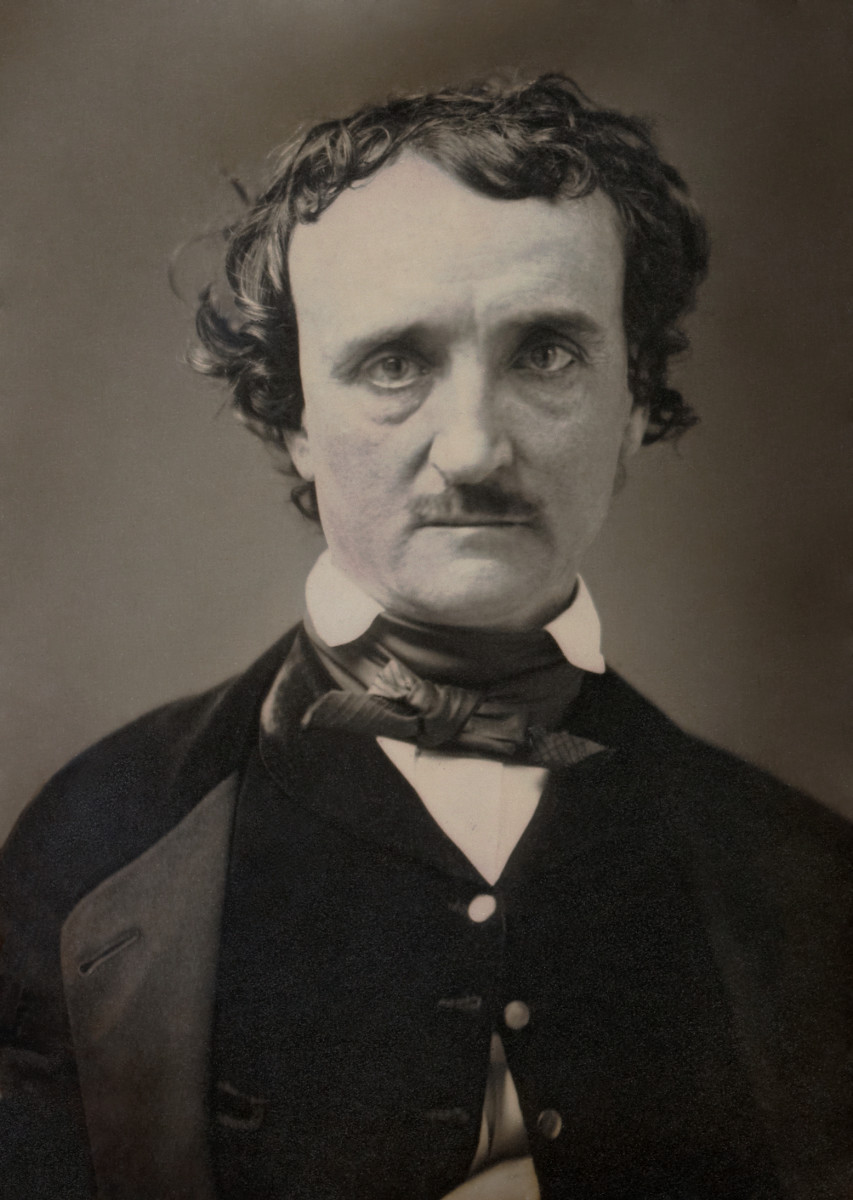

To understand William Faulkner fully, each of his works must be understood within themselves. For it is with Faulkner as it is with any genius, the scope of their achievement can only be understood when... - American Literature Classics: Interpreting the Climax of Edgar Allen Poe's Fall of the House of Ushe

In his The Philosophy of Composition Poe tells us that he begins writing with the consideration of an effect (1598). Almost all of Poes poetry and fiction give evidence to support Poes... - American Literature and Culture: The Roots of Manifest Destiny

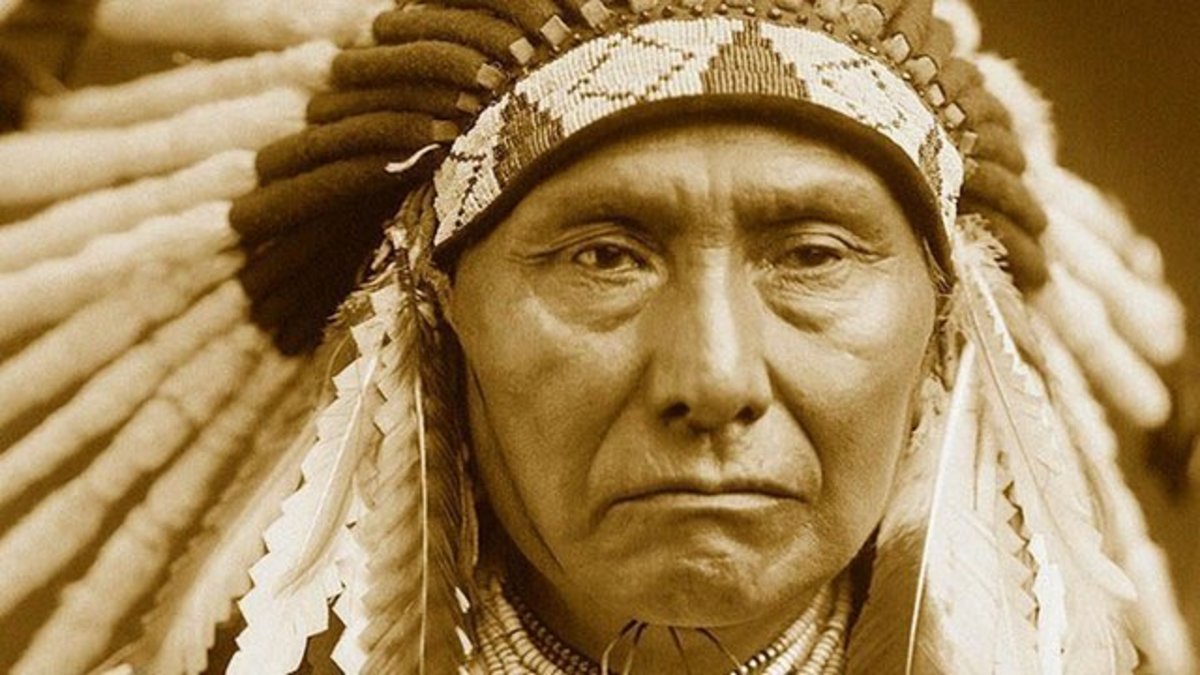

The discovery of the New World and the experience of colonialism in America produced a society independent of the Europe it left behind. This independence, forever cemented by the Declaration of Independence...