Elizabeth Barrett Browning's "Patience Taught by Nature"

Introduction and Text of "Patience Taught by Nature"

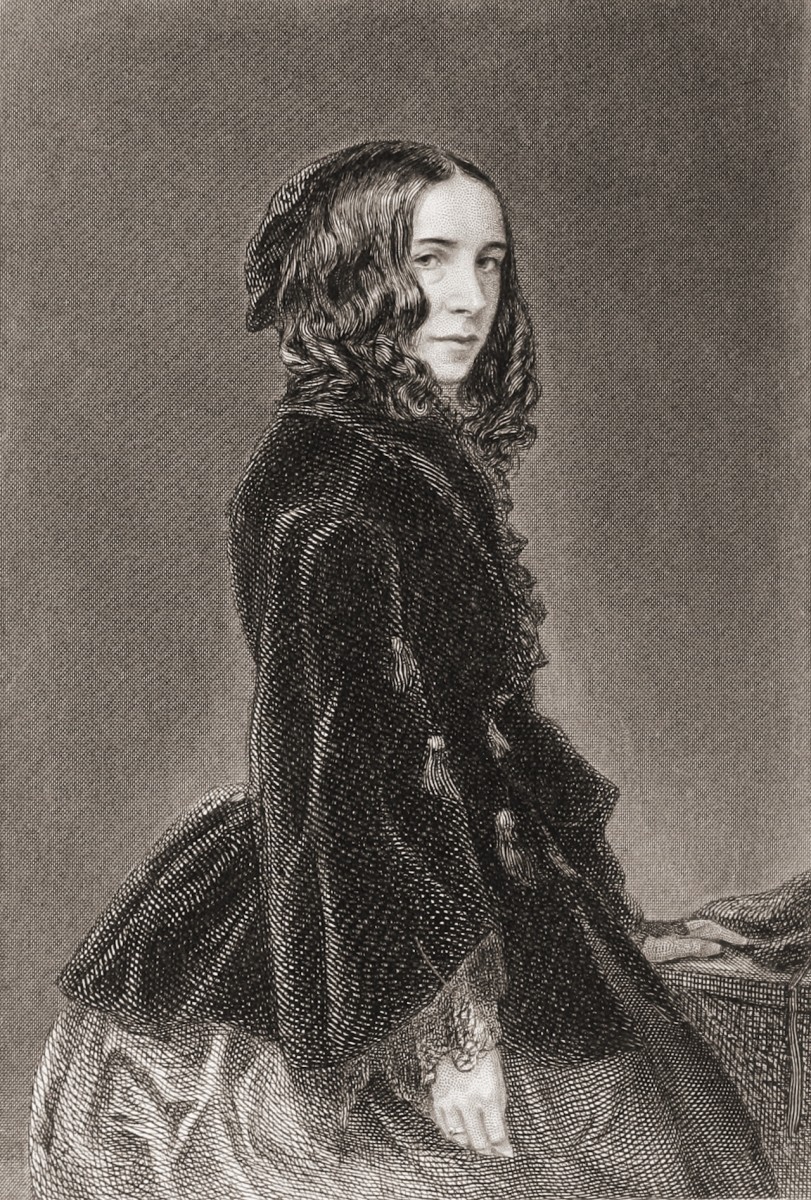

Elizabeth Barrett Browning perfected the Petrarchan sonnet form. All of her 44 entries in Sonnets from the Portuguese play out in that form.

This poem "Patience Taught by Nature" demonstrates her fondness for that form, as she contemplates the contrast between the human being's penchant for "patience" in meeting challenges with that of animals and creatures that appear and function in the natural world.

Patience Taught by Nature

'O dreary life,' we cry, 'O dreary life!'

And still the generations of the birds

Sing through our sighing, and the flocks and herds

Serenely live while we are keeping strife

With Heaven's true purpose in us, as a knife

Against which we may struggle! Ocean girds

Unslackened the dry land, savannah-swards

Unweary sweep, hills watch unworn, and rife

Meek leaves drop yearly from the forest-trees

To show, above, the unwasted stars that pass

In their old glory: O thou God of old,

Grant me some smaller grace than comes to these!

But so much patience as a blade of grass

Grows by, contented through the heat and cold.

Commentary on "Patience Taught by Nature"

Elizabeth Barrett Browning's romantic poem, "Patience Taught by Nature," is an Italian (Petrarchan) sonnet with the traditional rime scheme, ABBAABBACDECDE.

(Please note: Dr. Samuel Johnson introduced the form "rhyme" into English in the 18th century, mistakenly thinking that the term was a Greek derivative of "rythmos." Thus "rhyme" is an etymological error. For my explanation for using only the original form "rime," please see "Rime vs Rhyme: Dr. Samuel Johnson’s Error.")

Octave: Human Nature

'O dreary life,' we cry, 'O dreary life!'

And still the generations of the birds

Sing through our sighing, and the flocks and herds

Serenely live while we are keeping strife

With Heaven's true purpose in us, as a knife

Against which we may struggle! Ocean girds

Unslackened the dry land, savannah-swards

Unweary sweep, hills watch unworn, and rife

In the octave of "Patience Taught by Nature," the speaker begins with a mournful refrain, "O dreary life! we cry, O dreary life!"; she sets out on her journey of complaint against the nature of human beings, who are always bemoaning and decrying their trials and tribulations in life.

So many folks appear to be never satisfied, while the lower evolved creatures of nature seem to be models of serenity, cheerfulness, and patience—all the qualities that would make human life much more pleasant, productive, and enjoyable.

Then the speaker compares the ill-tempered human being to other forms of nature's life: for example, "the birds / Sing through our sighing." While the human sits and sighs and frets, the birds are constantly cheerful.

The birds and even the cattle "Serenely live while we are keeping strife." Human beings have the delicious advantage over the lower animals and creation because of the human ability to perceive "Heaven's true purpose."

That knowledge should be enough to act as a shield against all of human struggling. Even the ocean seems to soldier on, lapping upon the shores untrammeled by cares and woes. The land seems to carry on and "unweary sweep." The "hills watch" and do not become depressed.

Sestet: Calling on God

Meek leaves drop yearly from the forest-trees

To show, above, the unwasted stars that pass

In their old glory: O thou God of old,

Grant me some smaller grace than comes to these!

But so much patience as a blade of grass

Grows by, contented through the heat and cold.

Every year without complaint or misery, the trees throw down their leaves and then the human eye can catch a glimpse of the unruffled stars "that pass / In their old glory." Then the speaker bursts forth, mid-line, calling on God: "O thou God of old!"

The speaker is calling on God, as she had understood the concept in an earlier time, which she implies is more sturdy and durable than the uncertainties of the present.

The past is always a comfortable haven for those who are miserable in the present: the good old days, the glory days are concepts that people use to assuage their present uneasiness.

In the last three lines, the speaker prays to the God of old to give her just a small portion of the grace that these aforementioned natural creatures possess.

But she asks mostly for patience; she asks for the same patience that a "blade of grass" possesses as it continues to flourish "contented through the heat and cold."

The Pathetic Fallacy

The assigning of human emotion to animals and inanimate creatures in creation serves to communicate that emotion in a clear and often colorful way for the sake of art. That function is called the pathetic fallacy because in reality the human mind cannot know the true emotions of animals, trees, or the ocean.

Whether the animal feels as the human does must remain a mystery, but in poetry the notion can be useful as the poet attempts to describe the indescribable.

The notion of a constantly contented, patient nature is, obviously, a very romantic one. One might point out that nature is not the perfect model this speaker seems to believe it is. The speaker has no way of knowing if the birds are really always so cheerful, and why should they be?

They surely suffer greatly trying to procure their daily sustenance, building nests for their babies, whom they then must teach to be independent. And the oceans often whip up hurricanes and storms. And tornadoes sweep through the land uprooting trees. Rivers change their courses.

Many natural events involving animals and the landscape point to a lack of patience, grace, and serenity.

So while the poem makes a lovely, romantic statement that the human being would be better served to be more patient and have more grace, the human being could search in a better, more accurate place other than the lower animals and unpredictable nature to find a model for that grace and patience.

Perhaps the "God of old" might have an idea or two.

Related Elizabeth Barrett Browning Information

- Introduction to Elizabeth Barrett Browning's "Sonnets from the Portuguese" Elizabeth Barrett Browning's classic work, "Sonnets from the Portuguese," is the poet's most anthologized and widely published work, studied by students in secondary schools, colleges, and universities and appreciated by the general poetry lover.

Commentaries on Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnets

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnet 1 "I thought once how Theocritus had sung" Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnets from the Portuguese unveil a marvelous testimony to the love and respect that the poet fostered for her suitor and future husband Robert Browning. Robert Browning’s stature as a poet rendered him one of the most noted and respected poets of Western culture.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnet 2 "But only three in all God’s universe" In this sonnet, the poet creates a speaker who insists that the relationship is the destiny of this couple; it is karmically determined, and therefore, nothing in this world could have kept them apart once God had issued the decree for them to come together.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 9 "Can it be right to give what I can give?" Sonnet 9, from Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese, seems to offer the speaker's strongest rebuttal against the pairing of herself and her beloved. She seems most adamant that he leave her; yet in her inflexible demeanor screams the opposite of what she appears to be urging upon her lover.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 23 "Is it indeed so? If I lay here dead" In Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnet 23 "Is it indeed so? If I lay here dead" from Sonnets from the Portuguese, the speaker dramatizes the ever-growing confidence and profound love the speaker is enjoying with her belovèd.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Linda Sue Grimes