Everything Was Forever Until it Was no More: The Last Soviet Generation

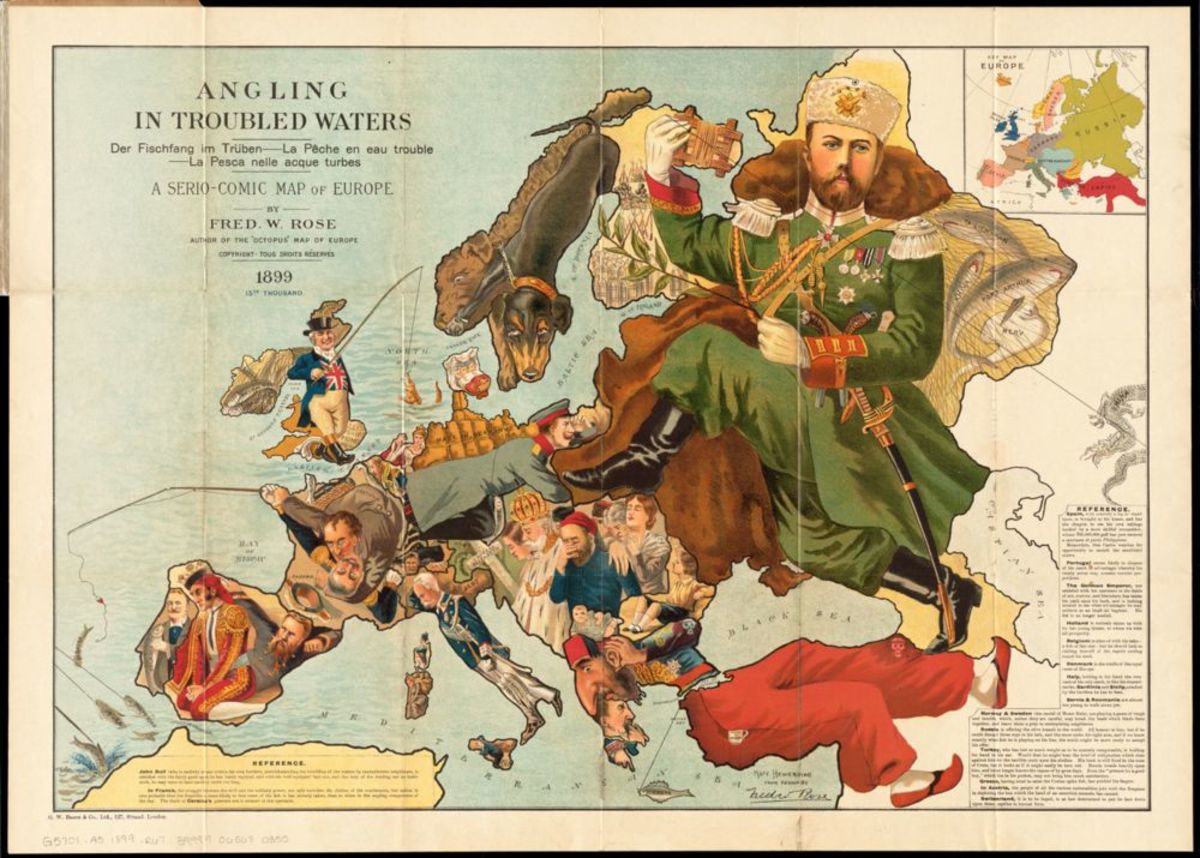

There is a famous quote about the Iranian Revolution that it was impossible until it became inevitable. So it was too, in the great Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the massive superpower that spanned ten thousand kilometers from Riga in the west to Vladivostok in the east, from Murmansk in the north to Tashkent in the south, possessing a massive space program, huge industrial accomplishments, a formidable scientific base, the world's most "scientific" ideology, and whose vast tank divisions were parked upon the Elbe waiting for the order to march to the Rhine. From both outside and from within, the Soviet Union appeared eternal, and then in a stunning few years, simply fell apart.

What was left was a strange paradox - how could a system so complete and so powerful, with people who seemed to believe that it would last forever, where it was unimaginable that things might truly change, and where many people genuinely believed in core elements of it, could then in the span of a few years collapse, and that it all seemed so obvious, clear, unsurprising as it happened in retrospect. In Everything Was Forever, Until it Was no More: The Last Soviet Generation, the anthropologist Alex Yurchak looks at this transformation and how it happened, and focused upon the structures of language and culture in late socialism - specifically, the concept of hypernormalization and modern ideology's structural validation.

As Yurchak points out, citing a collection of discourse and language analysis writers and thinkers and specifically the Lefort Paradox, in modernity power and ruling must be justified by some sort of ideology, and yet this justification is inherently fallible and often contradicted by the ideology itself. In the Soviet case the beautiful world of communism and individualism which had to coexist with control by the party and restrictions on individualism was a contradiction: it was never really resolved. The external justifier behind all of this was Lenin, and when Lenin began to crumple as the raison d'être of the system, everything else fell apart.

Of course, Lenin was dead by the mid 1920s though, so there had to be a way to continue to provide for an ideological headpiece: this would be Joseph Stalin, who routinely and regularly intervened and defined ideological beliefs in the Soviet Union. In The Last Soviet Generation, he comes across as a Communist Pope: the man who provided for the ideological definitions and determined beliefs. But Stalin then died, and in his wake, there was no replacement: instead became the process of hypernormalization, where doctrine became increasingly self-referential

In the Soviet Union, with the end of an external final arbitrer and source of authority with Stalin's death and subsequent discredit, ideology would become hypernormalized. Ther was no longer an ability to generate new concepts; and instead party texts, writing, speeches, started to become increasingly self-referential, formulaic, and interchangeable. Material would be recycled from one speech and document to another, and the voice of the author was eliminated. It was accepted that what was said did not have to bear a close connection to reality: what mattered was far more what it stood for than what it actually meant. A key example that Yurchak brings up is the lack of change in the reporting of Soviet state figures being interned in the Kremlin's walls: they were still reported consistently being buried, even as space became increasingly limited and instead only their ashes were put here - nevertheless, the actual words were unchanged.

With this, official doctrine strayed more and more from representing actual society, and became more and more formalized and in actual content meaningless. Nevertheless, it still served a role as a consensus, as providing for rituals: it was something that had to be carried out pro forma, in order to get on with "real work", as diaries about Komsomol, the Soviet youth organization, showed.

With this central point in place, Yurchak examines Soviet society more broadly, seeing the way that late socialism increasingly saw its official culture reinterpreted and modified by its citizens, even as they continued to believe in socialism - such as the growth of rock music, jeans, boiler-room workers who devoted their time to intellectual pursuits, and strange, post-modernist, avant garde culture groups acting out bizarrist scenarios. It wasn't that this was the simple official/unofficial culture long spoken of: rather, the state's culture could be interpreted in unexpected ways by citizens, who took its propaganda and writings in their own interpretations. The 1960s to late 1980s generation belief in what they were saying, but official propaganda's hypernormalization made it increasingly disconnected from everyday life, and when Gorbachev tried to reform it, he destroyed the legitimating factors and it all collapsed like a house of cards.

All of this fits into what I think of as a clear theme in history: that centralization and unification breeds strength, but also increasing fragility. The more centralized and rational/structured/streamlined something is, the easier it is for it to collapse, even as it simultaneously also is capable of marshalling its greatest strength. Great empires collapse to barbarian invasion with stunning speed while smaller states make for long grinding quagmires: attempts at "rationalizing" a power structure, from absolute monarchs to Napoleon to Hitler simultaneously make it far more vulnerable than before. A single node of power is fundamentally easy to overturn. In the Soviet Union, where absolutely power was concentrated absolutely into a single system that was universal, omnipresent, and invariable, so that famous films such as The Irony of Fate could parody this fundamental homogeneity and singularity of the system, it was easy for it to slide into chaos.

It makes me wonder about the fate of the United States, which similarly has its own increasing deterritorialization, homogenization, and people who have to belief in something simply to match what is expected of them, rather than what they believe in. But of course, it's always trite to say "but what if we were like that!" In any case, Yurchak provides a fascinating account of how the last generation of Soviet people thought and the way that ideology worked in the Soviet Union.